The Dunedin Sound: Some Disenchanted Evening is a visual celebration of the early years of the city’s post-punk music scene, which became so identified with the fledgling Flying Nun label. Edited by Ian Chapman – the University of Otago’s Bowie scholar – it contains a feast of photographs and ephemera, set lists and posters. Many of the posters have been treasured since they were first pulled off walls in the early 1980s. The chapters highlight the most prominent Dunedin bands of the period – among them, The Enemy, The Clean, The Chills, The Verlaines, Sneaky Feelings and Straitjacket Fits. Also included are several essays, including this one by Amanda Mills, AudioCulture writer and Hocken library music specialist. Did an actual Dunedin Sound exist? She considers the evidence.

--

“The Dunedin Sound is the sound of honesty.” – Martin Phillipps, Auckland Star (1982)

“That’s what I’m scared of with the Dunedin hype. If it does become a trend, that’s the end of it.” – Jeff Batts, Critic (1982)

--

In 1982, a small, insistent and growing movement in New Zealand’s independent music scene took root, begetting a phrase, “the Dunedin Sound”, which has been a curse and a blessing to most, if not all, musicians from that southern city.

Although Roger Shepherd claimed responsibility for it in the documentary Heavenly Pop Hits – The Flying Nun Story, the first use of the Dunedin Sound is attributed to The Clean’s David Kilgour, in the December 1981 issue of In Touch magazine. When asked if he thought there was a distinctive New Zealand sound, Kilgour replied, “No, but I think there’s a Dunedin Sound”, while bandmate Robert Scott clarified “it’s a good, raw sound influenced by what you heard on the radio as you grew up – the stuff from the 60s and 70s”.

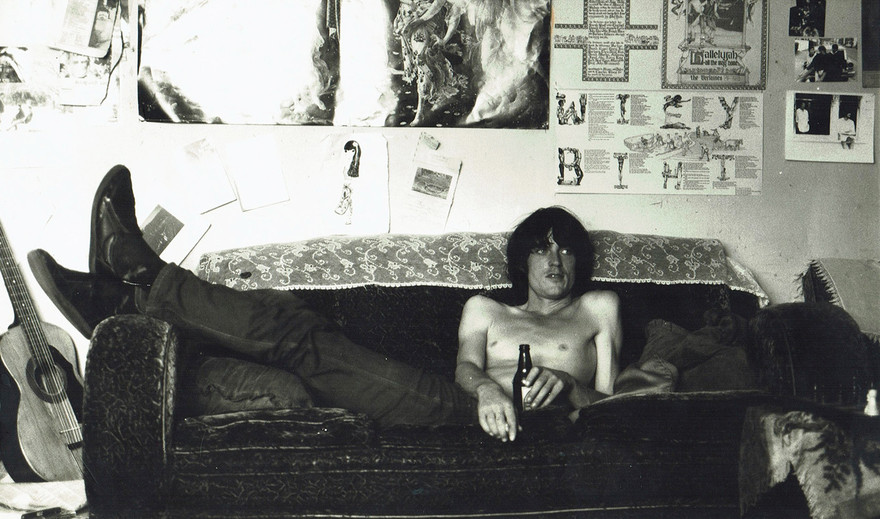

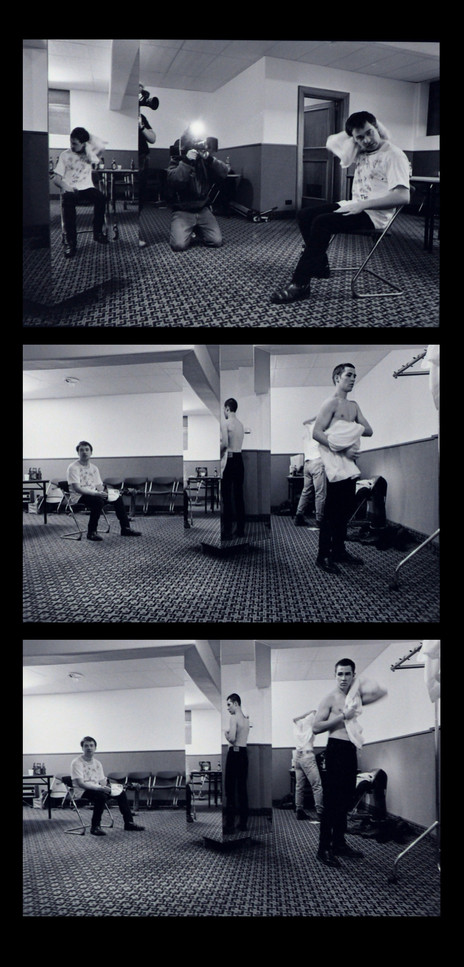

Graeme Downes of The Verlaines, relaxing at home, 1985 - Jo Downes

There are compelling arguments both for and against the existence of the Dunedin Sound.

From this point on, the Dunedin Sound was seized upon as being the “definition” of the music coming out of Dunedin. But was it really that all-compassing and inclusive? The camp may not be split evenly, but there are compelling arguments both for and against the existence of the Dunedin Sound.

So, what denotes the Dunedin Sound? To the casual observer, the essential elements of inspiration come up repeatedly: Dunedin’s often-inclement weather, and the city’s geographical isolation. Add to this the 1960s influences that beget the commonly described musical components (the guitar jangle and the drone), and you start to get the picture.

Roy Colbert, former owner of Dunedin’s famous (and influential) record store Records Records, and mentor to many local Dunedin Sound musicians, disagrees somewhat with the arguments relating to isolation and climate. “Things that people used to bring up, like the climate, the isolation, there’s nothing else to do, so you may as well go indoors and write songs … Virtually nothing happened for all that time [before 1980], so the weather never changed, the city never changed its population, nothing of all those things that were meant to be major ingredients for the Dunedin Sound ever changed, so I don’t think that’s valid.”

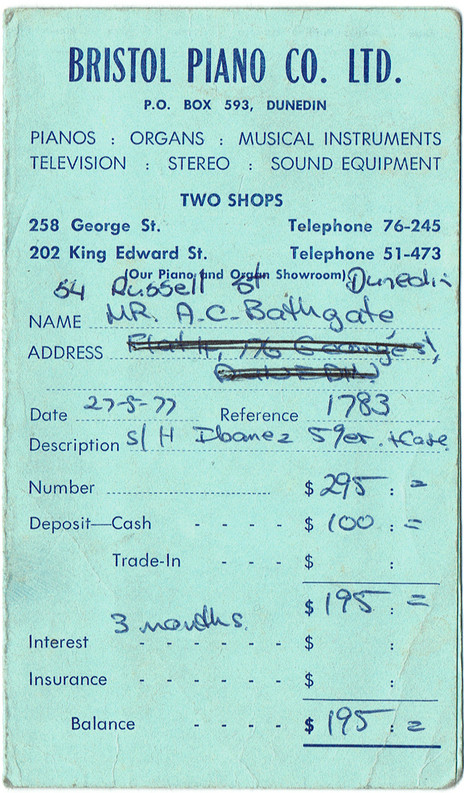

Alec Bathgate's HP agreement for his Les Paul copy guitar, 1977. This was later sold to David Kilgour and can be seen in most images of the Clean through the 1980s - Alec Bathgate

Dunedin may be at the bottom the world, but the city was not as remote and removed from culture as popular mythology would have us believe. In communication with Graeme Downes of The Verlaines, I found he believes that because the Dunedin Sound “was rather insular at its inception, influences were largely internal … because trends took so long to get here, people tended not to jump on them”.

However, Andrew Schmidt, writing for AudioCulture, points out that the same sounds were getting here (albeit a little more slowly), as local record stores were branches of those found in England, notably EMI. Also, the University of Otago was employing staff, and receiving students, from all around the country (and often internationally), who would bring with them their music collections and cultural knowledge. Locally, television music show Radio With Pictures (1976 to 1988; briefly revived in the early 90s) was playing some of the latest international and national sounds, which would seep into what Dunedin’s musical community was hearing.

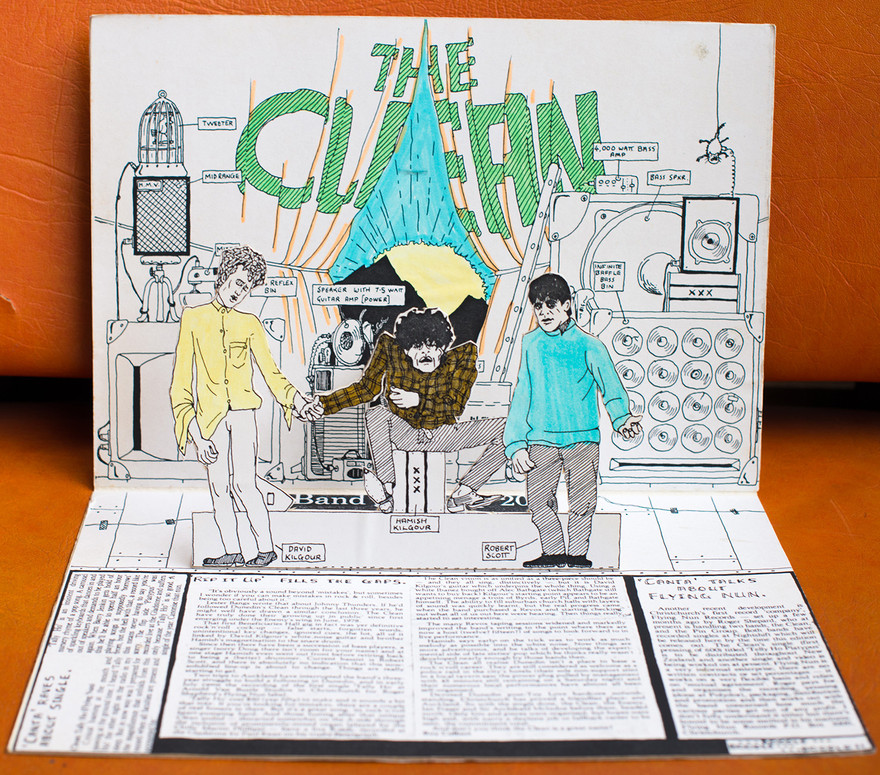

The Clean promotional pop-up, 1981 - Tony Renouf collection; photograph Alan Haig

Nevertheless, some musicians associated with the scene argued that isolation was a significant factor, with few models to base the songs on, and little access to what was happening in the world. “Not a lot happens in Dunedin; it’s a long way from everything, so people need to make their own entertainment,” Graeme Downes told the Chicago Tribune.

Straitjacket Fits’ Shayne Carter disputes this, writing in the Sunday Star-Times that “it wasn’t as though the Dunedin scene … was the result of some splendid isolation and the fact we couldn’t afford proper gear”. He also admits “we knew what was going on in the outside world … what was happening right in front of us was more relevant and important”.

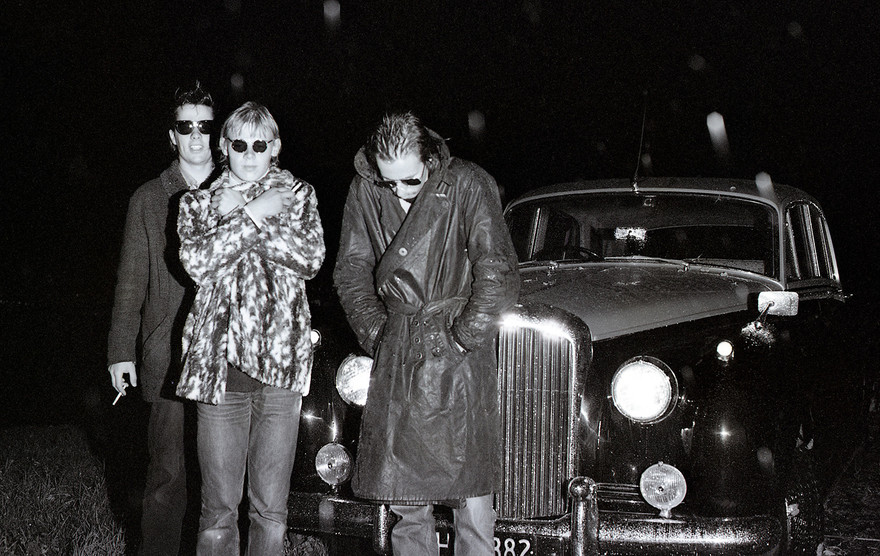

The Stones playing rock stars with a borrowed Bentley, 1982 - John Devereux

The weather, too, is another factor for much debate. The Chills’ Martin Phillipps, also talking to the Chicago Tribune, told them: “Dunedin has a cold, drizzly atmosphere over half the year. So, you generally stayed inside and practised, and made a lot of music.”

Shayne Carter agrees that the weather was a significant factor: “you could sit in your flat for days while you waited for it to clear outside. The weather there sure made you dedicated to your craft.”

Hand in hand with weather was landscape and environment – Carter speaks of wondering about the effect “of that small pocket of sky, framed by seven hills, with … disturbances and racing cloud. It’s an intense kind of canopy to be under.” Colbert agrees: “Not everyone was sequestered indoors writing songs; it’s a romantic image, but it’s not true.”

The Bats at Sammy's nightclub, Dunedin, 1989 - Gerard O'Brien

Looking at potential influences on Dunedin musicians is another step in unravelling any perceived similarities in sound. Three central influences appear again and again: a 1960s do-it-yourself (DIY) attitude; The Velvet Underground; and punk rock. The influence of the 1960s DIY ethos in music-making is evident when hearing the lo-fi nature of the music coming from Dunedin in the 1980s, as is “the jangle”: a textural guitar sound prevalent in the music of many (although not all) of the Dunedin bands, including The Clean, The Chills, The Verlaines, Sneaky Feelings, and Look Blue Go Purple. The psychedelia of the 1960s also makes an appearance, with bands like (the early) Pink Floyd influencing The Chills’ more whimsical material, such as ‘Kaleidoscope World’.

The influence of the 1960s was not lost on writers like Colbert, or the scene’s other major auteur figure, Chris Knox. “When they recorded the Dunedin Double EP,” says Colbert, “I remember Chris saying to me, ‘It will be interesting what people think of this, because it’s backwards, nothing new, it’s kind of 60s. People will wonder what this is.’ They weren’t breaking new ground, or they weren’t copying Auckland, and it was interesting that people found it original, and shatteringly interesting, and amazing … It’s actually essentially music that had been done.”

Straitjacket Fits set list, date unknown. - Stephen Kilroy collection

“The Dunedin Sound was famous for picking up on the cooler, edgier music sounds such as The Velvet Underground,” Brannavan Gnanalingam stated in The Lumière Reader in 2007. Indeed, the 1967 album The Velvet Underground and Nico introduced the drone, a guitar note or tone sustained by pedals, which produced a resonant effect, and proved very influential.

Colbert pinpoints one particular person: “When Toy Love came through Dunedin … they had a guy with them, he was in a Christchurch punk band [The Androidss]. His main song was ‘What Goes On’ by The Velvet Underground, which to me is pretty much the same as ‘Point That Thing’ or ‘Death And The Maiden’ or The Bats’ ‘North By North’ – pretty much a driving drone. And it’s amazing, ‘What Goes On’ … I think that’s a major influence on the Dunedin Sound, it’s never been brought up before, just this one guy, with that one song.”

The revival and influence of The Velvet Underground, and the persistent drone, is evidenced throughout much Dunedin Sound material, and is found particularly in the early songs of The Clean (‘Tally Ho!’), The Chills (‘Rolling Moon’) and the Sneaky Feelings (‘Be My Friend’), and continues in later recordings, notably Snapper’s 1988 eponymous EP.

The third commonly mentioned influence on the Dunedin Sound is punk rock, which affected (or infected) most, if not all, local Dunedin musicians in the late 1970s. The lineage of the Dunedin Sound can be traced back to Dunedin’s own The Enemy, a local punk group whose members included Chris Knox and Alec Bathgate (later of Toy Love and Tall Dwarfs). Although the band was short-lived, their legendary shows intimidated and awed the teenage musicians that came to see them, including a young Shayne Carter, who went on to form Bored Games, DoubleHappys, and later Straitjacket Fits (known in some circles as the “Best Band in the World”). Punk revolutionised and energised the local musical youth, although cultural revolutions in New Zealand’s identity – the Springbok Tour, and New Zealand sending a frigate to Mururoa Atoll in particular – also stirred up discord, and emerged in particular ways, even though not all writers were consciously writing songs of political dissatisfaction and protest.

Straitjacket Fits' audience at Sammys Nightclub, Dunedin, 1989. - Gerard O’Brien

Another element in the development of the Dunedin Sound is the cross-influence of the bands themselves. No two groups were identical, although many shared equipment, recording spaces and band members (the scene has been described as “incestuous” by many musicians and commentators), so they were aware of what each other was doing, and achieving.

Colbert observed this closely. “They go along and see The Verlaines, who play ‘Death And The Maiden’, and they think, ‘Shit, my song’s nowhere near as good as that’, so they go away, and they try and write ‘Death And The Maiden’ … Probably 10 people who were really, really good were all competing, which made it even better.” Carter concurred, telling the Sunday Star-Times that “we inspired each other and competed with each other, knowing every weekend we could go out and find someone else had raised the bar”.

The discussion on influences leads us into the crux of the matter: was there really a Dunedin Sound in terms of the music created by these talented musicians? Or was it purely a phrase picked up on to group all music coming from Dunedin? An article in the Otago Daily Times, simply called “Dunedin Sound?”, commented “last year it was heralded as a unique musical movement by some, though rubbished by others … the name may or may not have been definitive … [but] the label stuck”. Many of the new bands denied any connection to the Dunedin Sound, and the article surmised “perhaps any original local music … fits the label Dunedin Sound”. The debate over the existence of the subgenre still rages, often contentiously.

Is there validity in the phrase Dunedin Sound? Colbert certainly thinks so. “There was a Dunedin Sound, definitely, unquestionably. It’s kind of weird, the Dunedin Sound has got so much publicity, but of course the bands didn’t like it back in the time; they may put up with it now, because of the global recognition. I presume they didn’t want to think everyone sounded the same, because they don’t.”

Chris Knox agreed with this on the Heavenly Pop Hits – The Flying Nun Story documentary, declaring: “Some people, somehow, could find something in common between the classical rock of The Verlaines, the total out-and-out Stooge-craziness of The Stones, the twee little, happy little pop songs of The Chills, and The Byrds-cum-Tamla Motown sound of the Sneaky Feelings, because they all used guitars – that was the only common thread I could see.”

The Chills in the dressing room of the Dunedin Town Hall, 1990. - Gerard O'Brien

Any similarities between the musicians, it seems, were superficial. Musically, many bands shared the jangle and the drone: it features in the work of The Verlaines, The Chills, The Clean, Sneaky Feelings, and Look Blue Go Purple predominantly, although The Stones, The Rip, and Doublehappys occasionally featured it in their material.

Graeme Downes sees this as a unifying factor, and thinks the sound was there “for a while, and occasionally still is, jangly guitars with open strings … a technique that everyone used”.

However, these bands are dissimilar, a fact that became clearer as the 1980s continued; Look Blue Go Purple in particular used flute to differentiate their ethereal folk-pop. By 1985, Craig Robertson argues that “the common denominators, low standard of studio production, and technical ineptitude, were no longer there”, and many of the bands were investigating further use of multi-track equipment, although others preferred to adhere to the ideal of capturing the live sound on tape. Continuously developing sophistication within the songwriting and performance of these bands meant that their individual sounds were becoming even more divergent.

One unifying factor could be argued for the existence of the Dunedin Sound: the quality of the songs, and how they were performed and recorded. Graeme Downes views it in a particular light, speculating, “Dunedin and the bands in it that measured up … was a songwriting school … with very high standards”, while Craig Robertson considered “the ability to write what the aesthetic defined as a ‘good’ song was more important than gaining the skills necessary to perform the song”. In relation to the songwriting, most of the writers were not trained in the art (or craft) of songwriting. “That’s another Dunedin Sound thing, they were so primitive, they just worked within narrow parameters, and not many chords,” Colbert says. “But that’s one of the strengths, really, as opposed to learning music, and getting a Master’s degree or something, and then trying to write ‘Tally Ho!’.”

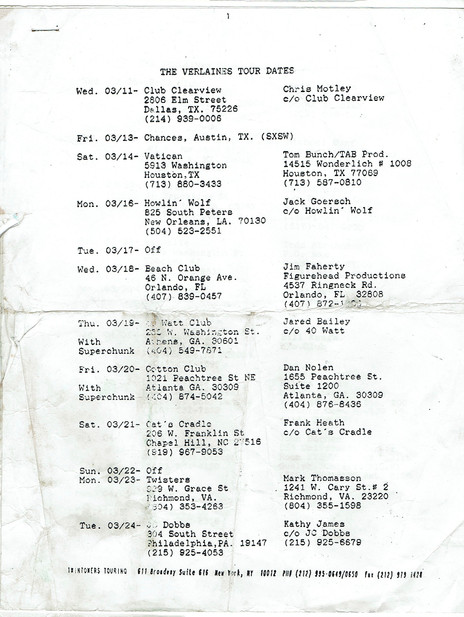

Verlaines tour schedule, 1991 - Graeme Downes collection

The songs themselves are strong; in fact, Graeme Downes has described them as “symphonic” in their construction, although he admits that not all songs have these qualities: “There are a good many that do, in The Clean, Chills, Verlaines and SJF [Straitjacket Fits] particularly … You really only have to point to the instrumental sections (not solos) and how much poetic work music without words does in some of the bigger songs.”

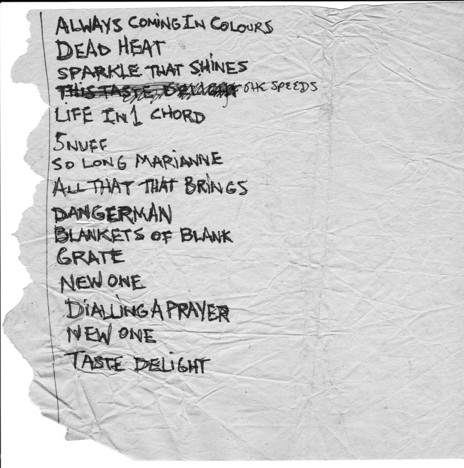

Downes has examined the melodic shapes within the music, making arguments for a Dunedin Sound stronger. “There are particular melodic shapes found in all the bands (4-3-1 usually, but semitone/major third on any scale degree) in the period where the phenomena was most concentrated (1980-ish to 1984-ish). Also the sound, but mostly the structural risk-taking … the shift in [Straitjacket Fits”] ‘This Taste Delight’ is pure daring on a par with the waltz in ‘Death And The Maiden’ or the D-major chorus in ‘Rolling Moon’ coming out of nowhere.”

In short, he considers the composers “pretty damned good”, and the subgenre’s collective body of work “unique”, and possessing “a rare quality in their tendency to court seriousness from time to time”. During a public talk in May 2016, Downes (appropriating Nietzsche) further described the importance of music to these artists, saying they “crossed the footbridge into music early – it became more important than life or death”.

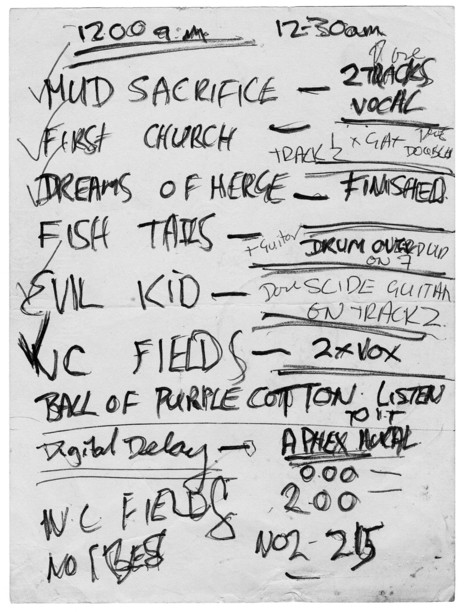

Engineer Stephen Kilroy's 'To do' list for the recording of Fish Tails, The 3Ds' first EP; Fish Street Studios, 1990. - Stephen Kilroy

Dr Matthew Bannister, formerly of Sneaky Feelings, has also written about the “Dunedin Sound”, in both his personal take on the subgenre, Positively George Street, and on independent music generally. In White Boys, White Noise, Bannister’s examination of rhythmic structures concludes that Flying Nun bands favour the beats of punk rock, although what he calls “1960s folk archivalism” and “intellectualism” appear within “metric experimentation”. He also considers reverberation of sound (the continuation or reflection of sound after it is produced) to be another common musical component of the Dunedin Sound, on both vocals and guitars, which would “fill out the minimal instrumentation” of bands who had fewer instruments (for example, The Clean).

The DIY attitude that prevailed with the bands extended to their performances (and promotional material – many gig posters and flyers were hand-drawn). Craig Robertson suggests that this was an attempt for musicians to remain in control of their material, not only in performances, but also through the recording and distribution processes. Retaining authority over the finished product lent an authentic air to the music, which was done for love, rather than financial gain.

A familiar remark on Dunedin Sound bands was that they were inept or “just okay” musicians, rather than possessing any major musical ability, although many would further develop their skills. This lack of ability was not lost on Roy Colbert. “All of my friends, who I grew up with in the 1960s and 1970s in bands, never got into a recording studio. Suddenly, in the early 1980s, everybody’s children are making records, and they can’t sing a lot of the time, they can’t play a lot of the time. And my friends are just dumbfounded! How does that happen?”

The 3Ds at Fryatt St wharf, Dunedin

This authentic nature extended into the recording studio, too, with many bands recorded quickly by friends or peers with limited, lo-tech or primitive equipment. Chris Knox and his 4-track recorder were put to good use (along with Doug Hood) recording The Clean’s Boodle Boodle Boodle EP, and a year later, the Dunedin Double EP. This gave the earlier recordings a unified, lo-fidelity sound, which would later be lost when the bands moved into studio settings, with bigger budgets and bigger expectations.

The idea that there is a Dunedin Sound perpetuates, some 35 years later. In July 2014, UK music magazine NME published an article on the wider Flying Nun subculture, “Songs in the Kiwi of Life”, and also listed their 17 “must-hear” Dunedin Sound tracks. Funnily enough, only 12 of the tracks were by Dunedin bands, and even then two were by bands who had been in existence for less than 10 years, and (at the time) were signed to Dunedin’s independent label Fishrider Records. Neither of these bands consider themselves part of the Dunedin Sound. The article in the NME (re-)introduces the notion of the Dunedin Sound to a wider, international audience, and lists the key bands of the subgenre and their key releases. Some of these are interesting choices – Modern Rock (1994) over Boodle Boodle Boodle (1981) from The Clean, anyone? The NME article was another catalyst for re-igniting the debate on the existence of the Dunedin Sound, an ongoing discussion about a subgenre that “is” and “is not” at the same time.

--

Amanda Mills has loved music since before she can remember, starting with Kate Bush and David Bowie, before discovering Dunedin bands like The Chills and Straitjacket Fits in what was her favourite place in Dunedin: Records Records music store. She writes about New Zealand music for New Zealand Musician magazine and AudioCulture, has worked with New Zealand music and sound collections in national institutions since 2003, and is currently curator of music and AV collections at the Hocken Library in Dunedin.

The Dunedin Sound: Some Disenchanted Evening is published in November 2016 by Bateman for $49.99.

–

Also related: