Wellington greets The Beatles

In 1964, on a sunny Sunday afternoon in mid-winter, 7000 Wellingtonians made their way to Rongotai airport to greet four Liverpudlian musicians who combed their hair forward. The Beatles’ eight-day visit to New Zealand has been well covered in the 50 years since they first touched ground in Wellington, and memories are conflicting and keep getting adjusted, but questions still remain. Why, so early in their career, did the band get such a reaction in New Zealand? And what song was it that Paul McCartney worked on later that night while trapped in the St George Hotel?

Photo by Morrie Hill. National Library of New Zealand

We already had rock and roll stars of our own: first Johnny Devlin, and more recently Max Merritt and The Meteors, and Ray Columbus and The Invaders. And we had already received several visits by stars of the early rock and roll era: first Johnny Cash and Gene Vincent, then Johnnie Ray, and only a few weeks before The Beatles, a package tour featuring Gerry and the Pacemakers, Dusty Springfield, Gene Pitney, and Brian Poole and the Tremelos. This April 1964 tour – promoted by Harry M Miller – was billed as “the wild Liverpool Sound show”, though only the Pacemakers crossed the Mersey. None of these visits compared to the welcome given to Nat “King” Cole, who drew 5000 Aucklanders – most of them young women – to Whenuapai airport when he arrived for a concert in January 1955.

With large, plastic tiki and a giant kiwi, The Beatles arrive in Wellington

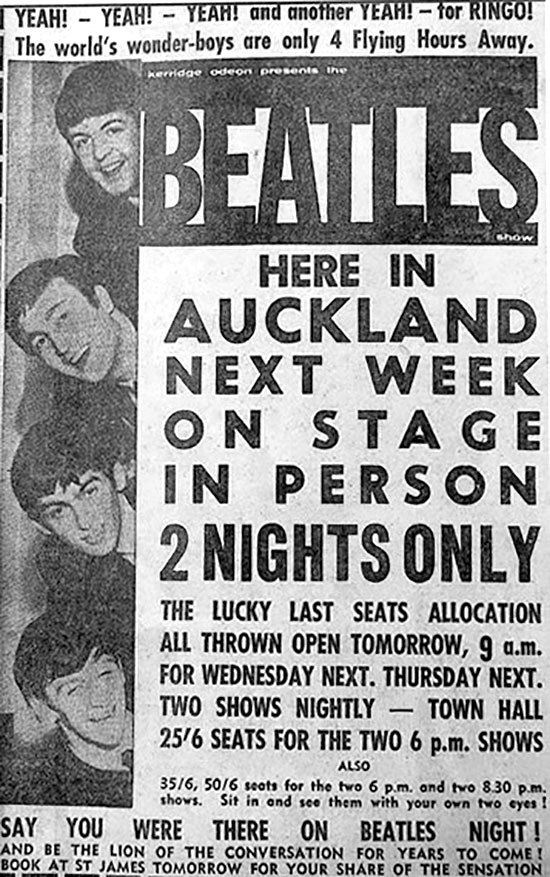

Tickets to the Beatles shows were priced from £1/9/6 to £2/10/6 ($60-$100 in 2013 dollars). A few months before the tour, Lew Pryme, a young Auckland reporter for Truth and an aspirant pop singer, went to the box office at the St James on Queen Street see the reaction when Beatles tickets went on sale. Unlike Australia, where Beatles fans had camped for two or three days, “We went down to get the story and low and behold, we were the first in the queue,” said Pryme. “The conditions were wet and cold, and soon there were something like three or four hundred fans behind us.”

Awareness of The Beatles changed quickly. From ‘Please Please Me’ on, all the group’s classic singles had been released in New Zealand on Parlophone through His Master’s Voice (NZ) Ltd, soon after going on sale in Britain. But in the weeks between the “Liverpool Sound” show and The Beatles’ tour, there was a deluge of extra releases. From late April through to June 1964, HMV released as New Zealand singles ‘Can’t Buy Me Love’ b/w ‘You Can’t Do That’ (from the film A Hard Day’s Night, which wouldn’t come out until July), and several other singles taken from early albums or EPs: ‘All My Loving’ b/w ‘Roll Over Beethoven’, ‘Twist and Shout’ b/w ‘Boys’, ‘Money’ b/w ‘Do You Want to Know a Secret’, and ‘Long Tall Sally’ b/w ‘I Call Your Name’.

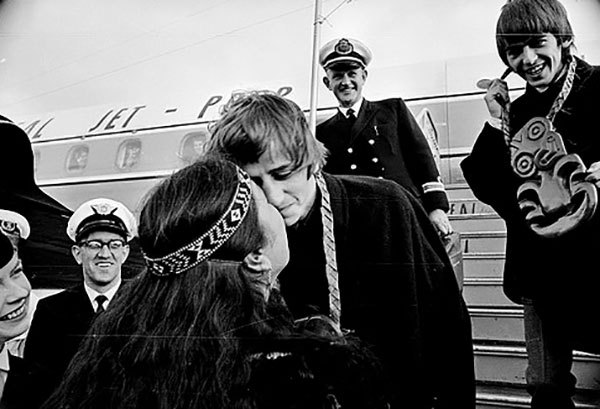

Paul gets a hongi in Wellington

Even with very little radio air-time being devoted to current pop music, it is no wonder that New Zealand was well prepared for The Beatles’ visit. Perhaps HMV realised how its USA equivalent, Capitol, had dropped the ball in the year prior to the group’s pivotal appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show four months earlier. Undoubtedly HMV’s parent company in Britain, EMI, had more clout over its colonial subsidiary. Whatever, the New Zealand company had its publicity machine well-oiled. The influential entertainment magazine Playdate featured The Beatles on the cover in April (their tour was promoted by Kerridge-Odeon, which owned Playdate). Also, footage of The Beatles’ arrival in Wellington shows many fans holding up copies of With The Beatles, their most recent album, and many other fans wave professionally produced placards of welcome.

Ringo is greeted in Wellington. Photo by Morrie Hill. - National Library of NZ, 1/4-071854-F

As The Beatles stepped down from the propeller-driven TEAL Electra plane which had brought them from Sydney, someone thrust a giant fluffy kiwi into the hands of Paul McCartney, then all four Beatles were given large green tiki made out of thin, moulded plastic. Next came a Māori pōwhiri, for which women from the local Te Pataka Māori Group had been recruited. One Beatle’s initial reaction to the Māori welcome was overheard by a nearby policeman: “We come in peace!” A recording unveiled years later suggests the quip was made by John.

The Beatles arrive in Wellington. Photo by Morrie Hill. - National Library of NZ, 1/4-071859-F

Each Beatle was given a hongi by the women. “I think it was Ringo Starr I picked out,” one of the youngest of the six women, Donas Nathan, told me in 1984. “Oh, it was quite an experience – I didn’t realised it was such a big thing until I got up there. The tikis were great big ones, and they were given to us by the Tourist and Publicity Department, I think.” McCartney received his hongi from “Aunty” Millie Clark. “She was like a kid too,” said Nathan, “and here we were – I was married at the time, with a child, and oh, I felt like a teenager! I just said to Ringo, ‘Kia ora and welcome to New Zealand’, and we pressed noses.”

Fans await the Fab Four in Wellington - Photo by Morrie Hill. National Library of New Zealand

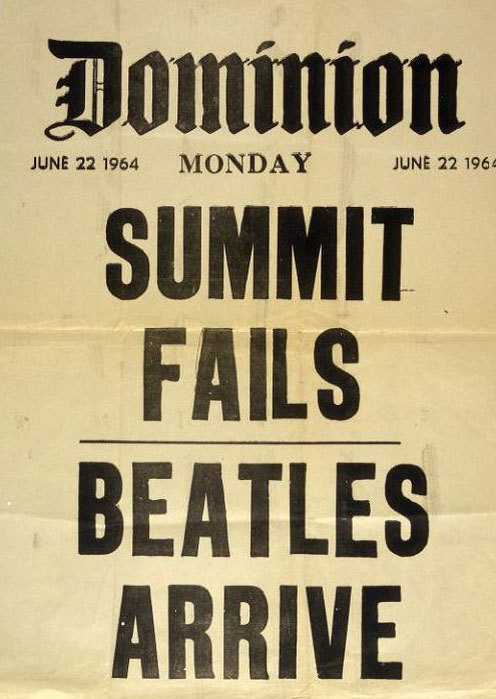

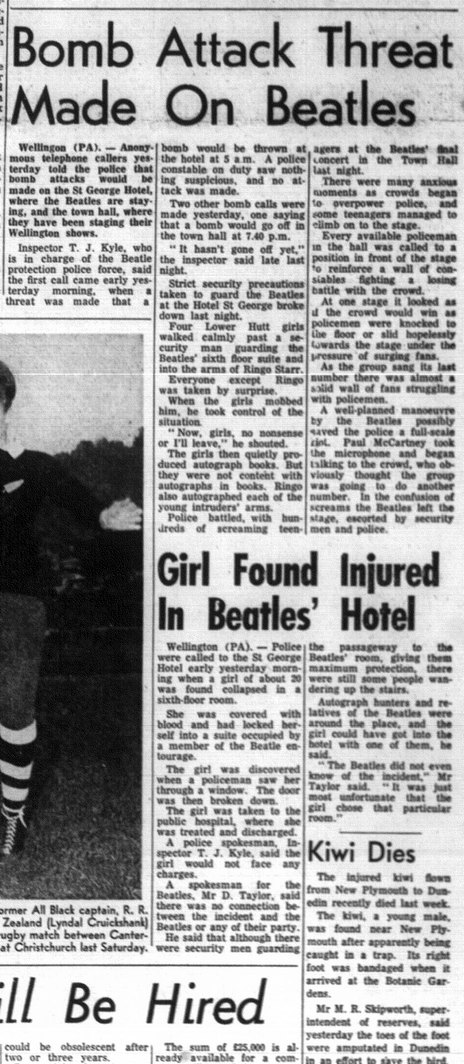

The two big stories of the day ... National Library of NZ, Eph-D-NEWSPAPER-DOMINION-1964-01

Still clutching their poi, and standing on the back of a slow-moving Holden ute, The Beatles were driven around the perimeter of the airport to greet the 7000 fans pressing against the chain-wire fence. Then they were driven into central Wellington – followed by a motorcade of fans in cars – to check into the St George Hotel on the corner of Willis and Boulcott Streets.

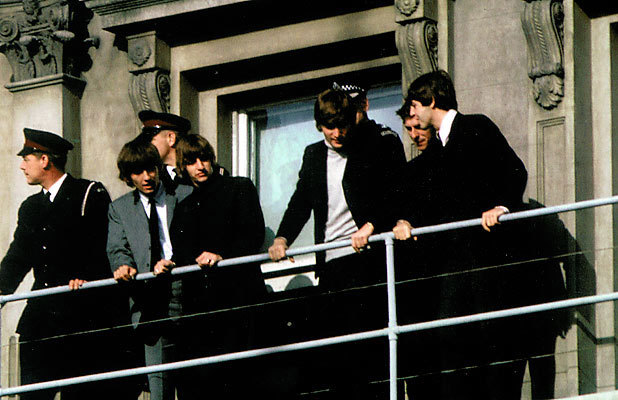

The Beatles on the balcony of the St George Hotel in on the corner of Willis and Boulcott Streets, Wellington - Photo by Morrie Hill. National Library of New Zealand

Crowds were already blocking the intersection, but the manager of the St George, Frank Drewitt, had been planning their arrival for months with Kerridge-Odeon, the Traffic Department and the Police. The crowd would eventually number 4000 as more fans arrived from the airport. Twenty policemen were at the front door to give the crowd the impression that was the way The Beatles would enter. But, said Drewitt, “I was waiting in the bottle store at the side of the hotel with about 12 policemen. On the pavement outside was a sergeant who, as The Beatles came down Willis Street, gave the signal: he lifted his hat and rubbed his forehead. I unlocked the door and the policemen stepped out as The Beatles’ car stopped at the kerb. The Beatles rushed out of the car like rats from a cage.”

The Beatles at their Wellington press conference - Photo by Morrie Hill. National Library of New Zealand

The group made their way to the third floor balcony to greet the fans, who were then told to disperse by an official with a loud-hailer: The Beatles weren’t going to be re-appearing. A frenzied press conference followed, attended by journalists such as Jim Hartley, female radio hosts Robin King and Doreen Kelso, and Johnny Douglas and Pete Sinclair of The Sunset Show, ZB’s hip, daily pop radio programme. Douglas got all The Beatles to record stings for the programme – “Hello New Zealand, this is Ringo” – and Sinclair ended up spending quite a bit of time in The Beatles’ company over the next couple of days, recording interviews for The Sunset Show and moonlighting for Australian radio.

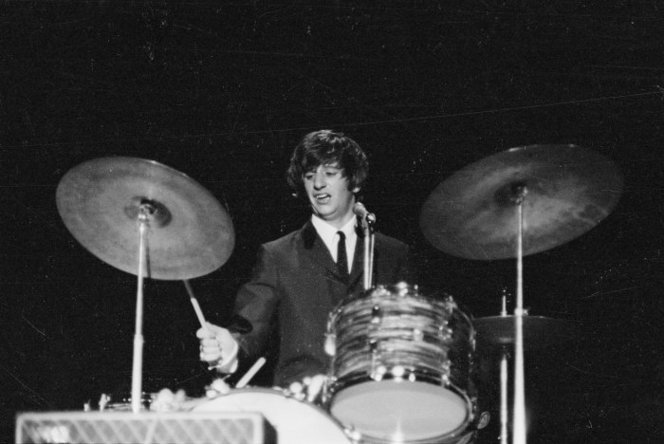

Ringo Starr on stage at the Wellington Town Hall, 24 June 1964 - Photo by an Evening Post Staff photographer. National Library of New Zealand

One thing that helped open the door for Sinclair was his role in getting an acoustic guitar for Paul McCartney to use while stuck in his hotel room. In 1984 Sinclair recalled: “I managed to secure a Spanish guitar for Paul McCartney on the Sunday, which was no mean feat. I got the manager of Begg’s music store to open up his shop and get one out for him. He wanted to work on a composition – but I’m sorry to say I can’t remember what composition it was. But in any event I managed to get him a Spanish guitar and in return for that I was allowed to get a great deal of exclusive material. I hung around in The Beatles suite with all The Beatles all the time they were in Wellington.”

Sinclair was stretching the truth here. The person who actually got the guitar for McCartney was a radio programmer from the war generation. Ken Avery was a leading jazz saxophonist and novelty songwriter (‘Tea at Te Kuiti’), whose day job was at the NZBC. In his memoir Where are the Camels? Avery writes that Douglas called him at about 7pm on the Sunday night to ask where he could get a guitar for McCartney to use, as all The Beatles’ equipment was locked in the Town Hall. Avery, who was well connected among jazzers, called around his musician friends but none wanted to lend “their beautiful Gibsons” to a mere pop group. “I rang Johnny Douglas back with the bad news. He said it didn’t matter what sort of guitar it was – anything no matter how old or cheap would do. Paul was going to re-string it to a ‘left-hand-drive’ as it were and practice on it.”

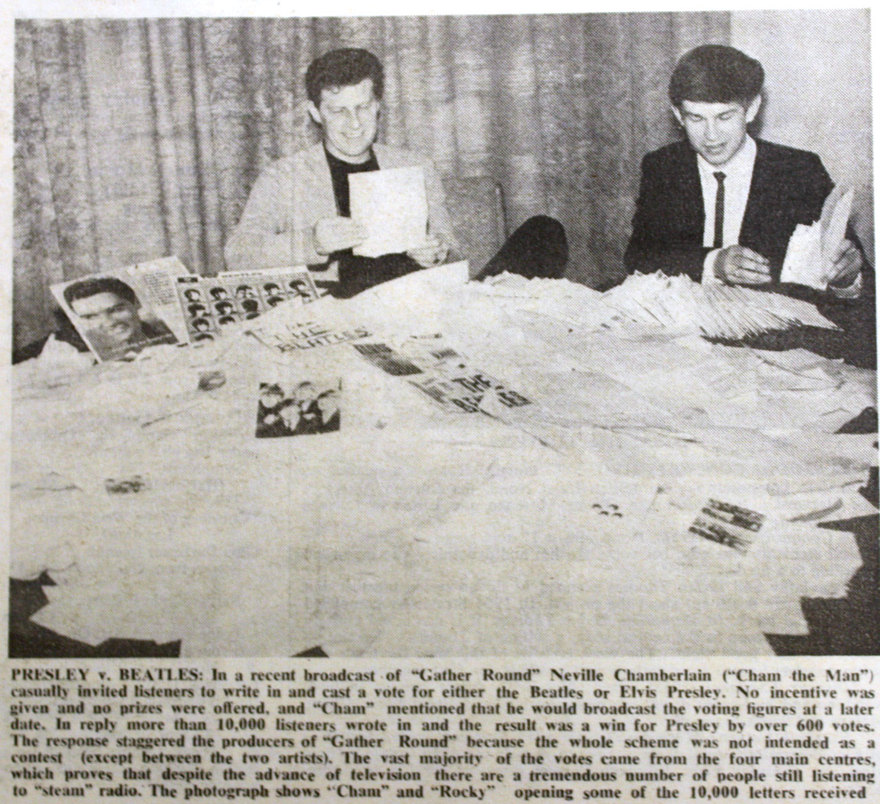

The results of a radio competition in Wellington in 1964. Counting the results are Neville "Cham the Man" Chamberlain and Rocky Douche who would later own Marmalade Studios.

Avery remembered his neighbours in Karori, whose daughter Susan was learning the guitar. “So I asked if I could borrow this guitar to lend to The Beatles for a few days. The answer was a firm yes, if I could get the boys to sign her autograph book.” Accompanied by his own daughter – an 11-year-old Beatles fan – he drove to the St George with guitar and autograph books. “Crowds of people were hanging round hoping for a glimpse of The Beatles. I had this cheap guitar in one hand, daughter Jane in the other, and as we approached the hotel at about 7.30pm I got a few remarks thrown at me from the crowd like, ‘Where are you going Ringo?’”

John with his second cousins, the Parkers, from Levin - Photo by an Evening Post Staff photographer. National Library of New Zealand

Unfortunately Avery’s daughter’s hopes of meeting the group were dashed when Douglas suggested he just hand the guitar over to one of The Beatles’ minders. When Avery returned a couple of days later to get the guitar – just before the group was due to check out – he and Drewitt asked one of The Beatles’ managers for the instrument. “He eventually found the guitar in one of the rooms. He said ‘Here it is – thanks very much.’ I said ‘Could you ask the boys to sign the front woodwork of it as a souvenir for Susie … ?’ This they did behind locked doors. I got Jane’s autograph book signed for good measure, but never actually saw a Beatle at any time.” Avery said that Susan’s father was later offered “£200 for that £8 Beatle-signed guitar. I hope Susie’s still got it, and left it strung the wrong way round to prove that Paul really did play on it.”

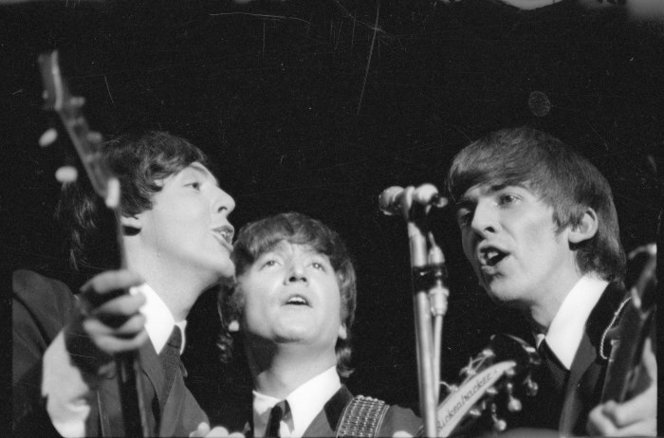

Paul, John and George, Wellington Town Hall, 24 June, 1964 - Photo by an Evening Post Staff photographer. National Library of New Zealand

Drewitt was an old-school hotel manager. He was still the manager when I asked him about the visit 20 years later. He cautiously wrote out his memories: “During their stay, school girls tried climbing up the fire escapes after school. They’d get to the entrance of the suites but were put in the lift and were sent back to the ground floor.

An unfortunate incident at the hotel in Wellington

“The only unpleasant incident was when a girl who had booked herself into the hotel tried to persuade a security guard to let her into The Beatles’ room. When he said she had no chance, she threatened to cut her wrists. He didn’t think she was serious, but when he ignored her, she took out a razor blade and slashed her wrists. She rushed back to her room and bolted the door. But I noticed the window to her room was slightly open, so a policeman got out onto the fire escape, pushed it open and got inside. She was there with a towel wrapped around her wrist. We sent for an ambulance and she was taken to hospital.

“The Beatles were playing a big game, with big money at stake, so they couldn’t afford to put a foot out of step. We had no problems with them, but the support band [Sounds Incorporated], who never had anything to do with The Beatles, played up – they messed up their rooms, damaged furnishings, even slashed some mattresses.

“But The Beatles were happy: they stayed in their rooms, where they ate all their meals and made a lot of toll calls home.”

Fans at Wellington Town Hall - Photo by Morrie Hill. National Library of New Zealand

One who penetrated the inner circle was Dianne Cadwallader, reporter for the shortlived Count Down magazine (and later, manager of Mr. Lee Grant). She managed to convince press agent Derek Taylor to get an interview with the group by bowling up on the Monday morning. While talking with them, she heard screams of “We love you Beatles” drifting up from the fans’ vigil in Willis Street, six floors below. “I pulled back the curtain to glance out,” she wrote. “Ringo came over and quickly pulled me away. ‘Don’t do that,’ he said. ‘They’ll think we’ve got birds up ’ere, and want to come up too.’ He laughed a kind of lop-sided chuckle.” George then wandered by, dressed in “a striking pair of red and black Chinese-style pajamas.”

Fans! - Photo by an Evening Post Staff photographer. National Library of New Zealand

Another who got an interview was Victoria University psychology lecturer Tony Taylor, who wanted to examine “the general personality pattern of The Beatles fans and the specific clinical features of hysteria and of neuroticism that were attributed to them.” Taylor interviewed Lennon, and attended one of the concerts. Under his coat he had a small reel-to-reel tape recorder – which mostly picked up screams, his main interest – and he had a dozen psychology students around the hall taking notes on fans’ behavior. Later, he got the young composer and music lecturer Jenny McLeod to analyse the beats versus screams ratio on the tape. “She found a selection of Beatles tunes varies from 67 to 200 beats per minute, with a mean frequency of 135,” Taylor wrote in his memoir. The academic paper he published was called Beatlemania – the Adulation and Exuberance of Some Adolescents.

Drewitt’s wife Ayline acted as the group’s matron while they were in the hotel. After standing on the balcony with them, dressed in her fur coat, she attended to their needs. Each morning about 10.30am she used a special knock on their door, and asked them what they wanted for breakfast. “They were always in their pajamas and dressing gowns, they felt the cold; they had the central heating up to a temperature that you could hardly bear. They loved it, they’d just come from Hong Kong to Wellington.”

All Ringo wanted was eggs, boiled for two minutes. “And I want it roonny,” he would insist. “The other boys used to have a good breakfast, cooked, and the rest of the day seemed to me to be spent putting toll calls back to their girlfriends in England.” John Lennon asked Ayline, a former hairdresser, to trim his hair; she also pressed their suits, and arranged a light pre-concert meal (“Apple pie, mince meat, steak”) and an après-gig supper (chicken, ham salad). “Then they’d perhaps have a few drinks, but very little. They weren’t drinkers, not in those days.”

After the first two shows on Monday night, there was a small gathering back in the hotel; The Beatles shared twin rooms, which also had lounges. Cadwallader, who attended the shows with Derek Taylor, wrote that when the other Beatles went to bed – Ringo in his pink pajamas – McCartney entertained those left at the small party with the acoustic guitar.

It gets a little out of control at the second Wellington show - Photo by an Evening Post Staff photographer. National Library of New Zealand

Ayline asked The Beatles if they wanted to meet any girls during their visit: would they like to have a little supper party? “They weren’t greatly interested in meeting any girls,” she recalled. “But they thought about it and said, ‘Yes, you ask some girls, providing that none of them talk to the press. Not that they did anything that the press couldn’t write about.” From her beauty salon contacts Ayline chose the girls “very carefully. I knew I had to choose nice girls, nice nice nice girls. Nicely dressed, clean, attractive and interesting. I took the girls up and we had a lovely evening. They sat on the floor and played their guitars, ate their food and they really relaxed. They had some drinks but no way were they excessive.”

While there is no evidence to suggest anything disreputable took place while The Beatles visited New Zealand, I did get the feeling that Drewitt and his wife had signed an old hoteliers’ pact that prevented them from saying anything controversial.

John Lennon interviewed in Wellington

Ringo Starr interviewed in Wellington

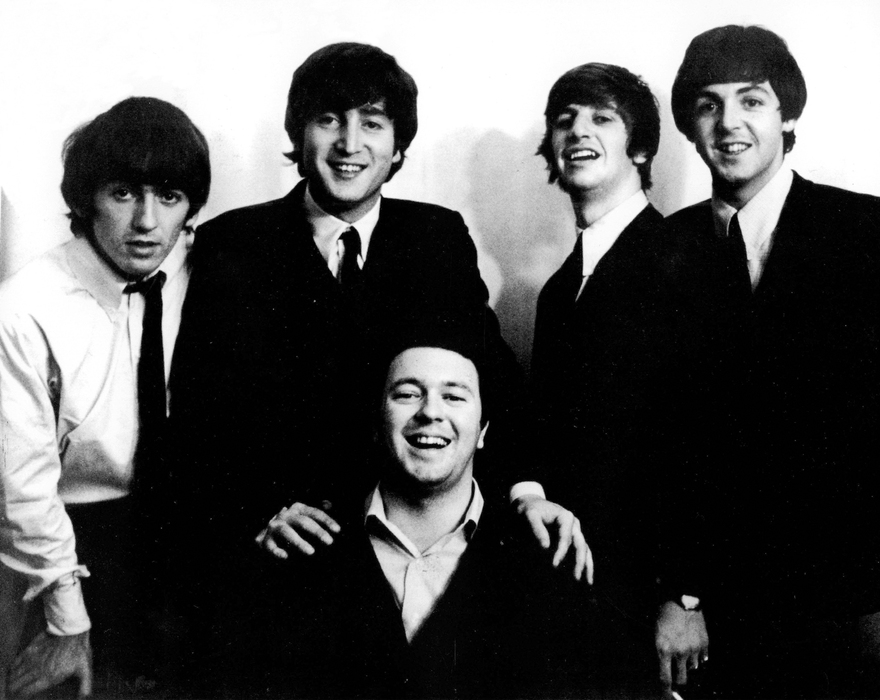

The biggest fuss came at the first Wellington concert, at 6pm on June 22: the group was angry that the Town Hall’s in-house PA was woefully inadequate and underpowered. Johnny Devlin, one of the support acts, spoke to the volume-hesitant Town Hall sound man, and offered to help improve the PA for the next day’s two concerts. He contacted Philips Industries and an alternative PA was hired. A roadie who helped set it up told me the replacement PA included several 100 watt amplifiers, a big Altec flare speaker and a couple of 15-inch speakers by the organ at the back of the hall, and a couple of columns of speakers on each side of the stage. When Devlin was asked what he wanted in return, he just said “a photo with The Beatles”. The group obliged.

Johnny Devlin with The Beatles

The police were unprepared for the frenzied reaction of the fans at the concerts. At first the constables sat in the front row, with their helmets underneath. They found this left them flat-footed when it came to the stage invasions that constantly took place. So for the second show they were seated in front of the stage, but facing the audience.

Everyone mentions the noise: the screams drowned out the music. “It was hysteria,” said Greg Cobb, who was 14 and later worked in the music industry. “You could only hear the opening of every song.” Another Wellingtonian, Barney Richards, said, “As soon as they came on stage it was one continual scream. I was fairly close to the stage and above this continual scream I could catch occasional snatches of songs. I heard a few bars of ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ and then nothing more, just this scream. You couldn’t hear the music, you could just see them mouthing the lyrics.”

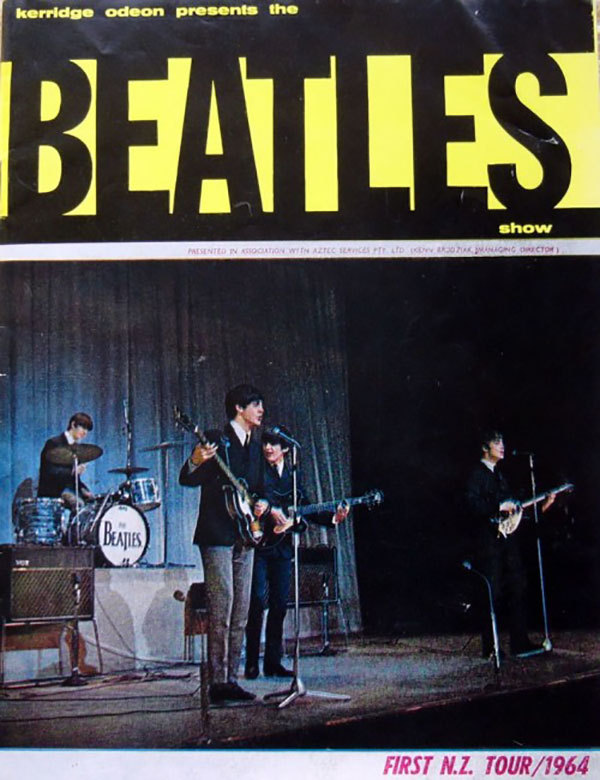

The Beatles programme cover

More pages from the 1964 programme

The two songs mentioned most by the people who were at The Beatles’ New Zealand concerts are ‘Till There Was You’ – a gentle ballad from The Music Man musical, for which the crowd quietened down – and ‘Boys’, because it was Ringo’s show-stopping moment. “As soon as he started singing ‘Boys’, the place went into bedlam!” said Richards. “I saw the Stones, the Dave Clark Five, Freddie and the Dreamers, Roy Orbison, the Hollies, the Pretty Things, P J Proby – all the major groups of the day. But I never saw anything like The Beatles. At least you could hear those other artists, and appreciate the music. But the Rolling Stones never got a reception like this.”

John leaves Wellington - Photo by an Evening Post Staff photographer. National Library of New Zealand

When The Beatles flew into Whenuapai airport, west of Auckland, on Wednesday 23 June, only about 300 fans were there to greet them. They got just a glimpse of the band, as officialdom had decided to bring the plane to a stop in a maintenance area 400 metres away, then whisk them away in a limousine. In the city, 2000 fans were waiting outside the Royal International Hotel on Victoria Street. Trapped by the fans, The Beatles’ limo inched through the crowd towards the loading bay, pushed by tour managers Neil Aspinall, Mel Evans and Lloyd Ravenscroft. It was 20 minutes before the area could be cleared of fans and the group could get out of the car. They were angry at the lack of protection by the police, whose attitude was summed up by the Inspector of Police. He told a member of The Beatles’ entourage, “We didn’t want ’em here, and I don’t know why you brought ’em.”

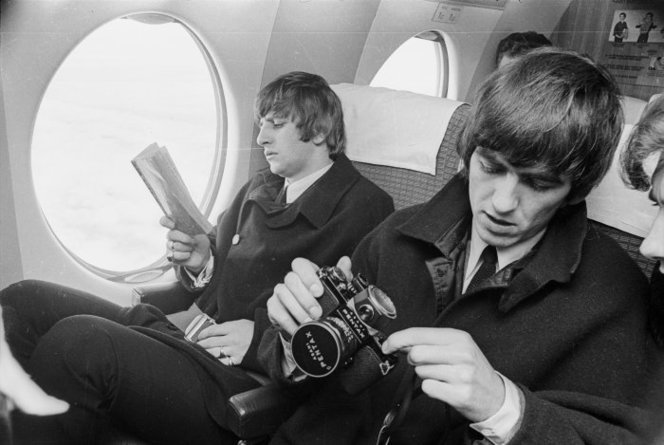

Ringo and George on the NAC flight from Wellington to Auckland - Photo by Morrie Hill. National Library of New Zealand

Lennon said later, “It was a bit rough. I thought definitely a big clump of my hair had gone. I don’t mean just a bit. They’d put about three policemen on for 3000 or 4000 kids and they refused to put more on. ‘We’ve had all sorts over ’ere, we’ve seen them all,’ they said, and they had seen them all as we went crashing to the ground.” Angry, Lennon threatened he wouldn’t perform that night unless more police were on duty.

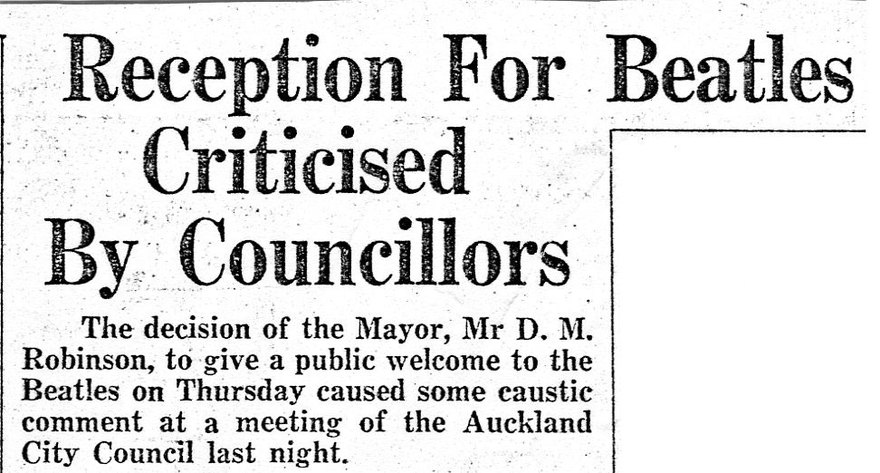

Auckland also provided a silly civic stoush when Mayor Dove Myer-Robinson wanted to give the band an official welcome; there had been one for the Vienna Boys Choir a week earlier, and the following week there would be another for pianist Arthur Rubenstein. The mayor’s council wasn’t keen, mainly at the cost of £60 to the ratepayers, but also because they didn’t approve of The Beatles. In particular, Rugby Union-stalwart Tom Pearce was dead against, but he could have been describing the behavior of the All Blacks and their fans when he said: “If we are going to pander to the hysteria, antics, adulation, rioting, screaming and roaring and all the things these bewigged musicians engender, then I think we should make a point of honouring any youths with sporting backgrounds who are at least trying to get in the best traditions of the young men of this nation.”

The Beatles at Auckland Town Hall, 24 June 1964. - Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 580-10702

In the end the impasse was solved when it was decided that a civic welcome was appropriate, but not a civic reception. The Mayor would wear his chains of office, but not his robes. Another establishment body that disapproved of The Beatles’ visit was the Auckland Education Board, whose officials took the names of school-age fans who attended the welcome outside the Town Hall, and said they were going to prosecute their parents.

Excerpt from the minutes of the Auckland City Council protesting The Beatles reception

The Beatles arrived late. The police had declined to provide an escort for the short journey from the Royal International to the Town Hall. The chief constable, Superintendent Quinn, said, “We provide such escorts only for royalty and other important visitors.”

The crowd was estimated at 7000, and the only negative notes came from those who carried an effigy of Tom Pearce, and the flat singing of the mayor, who called for the crowd to sing ‘Now is the Hour’ but ended up doing it alone. The Beatles attended for 25 minutes, and ended up standing on their chairs so they could be seen. “The Māori singers and dancers were great,” George Harrison said afterwards. “I liked the pois.” Lennon responded, “Pois? Isn’t that what Ringo sings?”

The Beatles at their Auckland reception, applauding Māori performers - Simon Grigg collection

At the concert, it was mayhem again. As was usual for the time, the show had a packaged, variety-style format. Comedian Allan Field acted as compere, warming up the crowd then introducing Johnny Devlin. Australian singer Johnny Chester followed – both singers were backed by well-groomed Melbourne group The Phantoms – and then, horn-based instrumental group Sounds Incorporated.

The Beatles with the Mayor of Auckland, Dove-Myer Robinson - Simon Grigg collection

Finally, The Beatles came on, playing between 26 and 28 minutes a night, rattling through a set-list that on this tour was usually ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’, ‘I Saw Her Standing There’, ‘You Can’t Do That’, ‘All My Loving’, ‘I Wanna Be Your Man’, ‘She Loves You’, ‘Till There Was You’, ‘Roll Over Beethoven’, ‘Can’t Buy Me Love’, ‘This Boy’ and finally ‘Long Tall Sally’. (Most fans I have talked to who attended one of the concerts mention Ringo singing ‘Boys’, although this doesn’t tally with online set-lists. Perhaps they are confusing it with ‘I Wanna Be Your Man’, which he sang, but it is never mentioned, neither is the slow three-part harmony ballad ‘This Boy’. But as Derek Taylor once told me on questions of Beatles accuracy, “I always trust the fans.”)

The Beatles in the Auckland Town Hall - Richard Morris collection

Lew Pryme recalled, “It was the first time I’d ever been exposed to the mania and fanaticism of a screaming teenage audience.” Broadcaster Barry Holland said, “When The Beatles came on stage there was scream after scream, and I’d never experienced anything like this even though I was a teenager myself. We’d heard about it, but this was absolutely fantastic. The atmosphere was electric in there when John Lennon first got up to sing at the microphone.” Booking agent Benny Levin told me he “vividly remembered the concerts” but he came out with “the most shattering headache I’ve ever had in my life.” The screams didn’t just come from teenage fans, said Levin: “I would say they also came from a lot of middle-aged ladies that were there as well. It was hysteria with the young girls at that show, and they were fainting all over the place. The St John Ambulance men were dragging them out like you wouldn’t believe.”

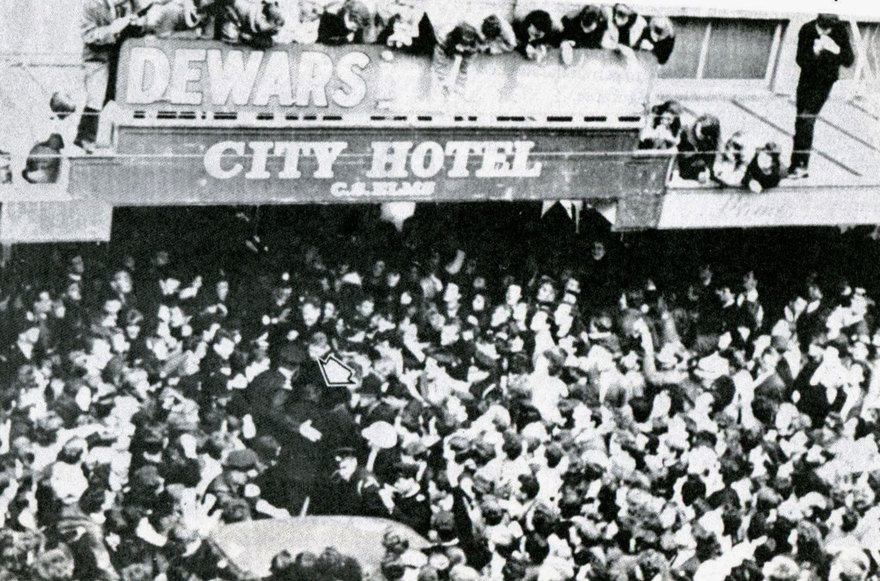

The crowd at the City Hotel, Dunedin. The arrow points to the band.

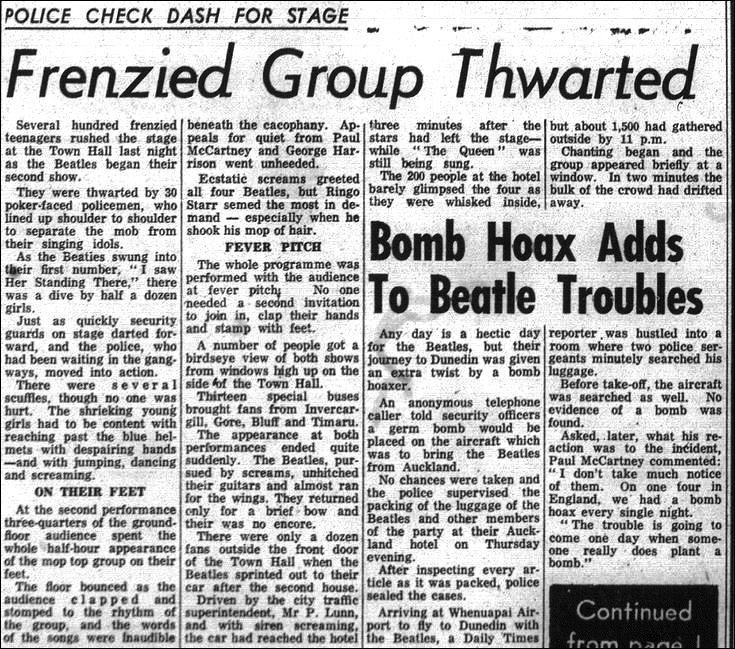

On Thursday 25 June, The Beatles flew to Dunedin. Their plane was 30 minutes late because a phone call had been received in Auckland saying there would be a “germ bomb” on board. Suspecting it was a prank from a member of the tour entourage, an Auckland police inspector reportedly locked the bands’ stage gear up for the night at their headquarters, and his men searched through the personal luggage of the party.

The incident that dominated The Beatles’ visit to Dunedin occurred when they arrived at the City Hotel. The police were unprepared for the hysteria among the 2000 people outside, who crowded the entrance and climbed onto the verandah above. The police took 10 minutes to form a gap in the crowd, and were jostled as they escorted the band. John Lennon was the last out of the car and by this time the police and security men had had enough. Dunedin broadcaster Neil Collins remembers the police picking up Lennon and throwing him through the front door. “I mean that. He was airborne when he reached that lift, and he was wearing leather pants and he cut his knee open on the iron of the lift.” Lennon stormed up to his room on the third floor, and refused to attend the press conference.

"Germ" bomb threats on the flight to Dunedin

That night, Collins was asked to be a decoy while The Beatles were sneaked into the Town Hall. With him was Russell Clark (later a business partner of Benny Levin and Craig Scott), Max Merritt and one of his Meteors. “The promoter said, ‘If you do this for us you’ll get to meet them later for supper. Turn your collar up, comb your hair forward, put your head down and race through the crowd to the limousine. It’s as simple as that, lads.’ We all thought it was great fun, so we did it, but as we did the crowd surged forward and there were people yanking and pulling at our hair. At that moment I wondered why I’d said yes, because it was quite terrifying.

“Before the car could move off the noise inside was deafening, with everybody bashing on the outside, and there was lipstick smeared all over the car. So off we went, and I can still see two old ladies outside Hallensteins waving frantically, so of course we got right into the act and waved back.

“Meanwhile The Beatles scurried out the back entrance of the hotel amongst trash cans and rubbish and got into a little Ford. They went around to the bottom end of Moray Place and came in the side entrance. They were in and out before anyone ever knew.”

Collins said to Paul McCartney: “I can’t believe you go through that performance every time you get out of a car to arrive at a hotel or concert. You must be battered and bruised all day. And he said, ‘Look we told your bobbies here, you’re going to have crowds and pushing and shoving. They said to us, ‘Don’t tell us about crowd control – we’ve had Vera Lynn through here twice’.”

Wayne Mowat, a Dunedin teenager and aspirant musician who later became a long-serving RNZ broadcaster, went to the 8pm show. “When we arrived I remember all the school girls and their mates were in raptures about the first show. Some of the girls were almost hysterical. That was the effect The Beatles had.

“We were about the eighth row from the front, and we were all quite well-built schoolboys and when The Beatles came on, we were suddenly at the back. There was a rush forward as soon as The Beatles came on in their mop tops and McCartney and Lennon started shaking their heads. That’s when hysteria really took over. The show up till then had been pretty sedate. They had Johnny Devlin on first and a comedian who introduced The Beatles but he was drowned out. After the concert everybody streamed down to the City Hotel and chanted out ‘We want The Beatles, we want The Beatles!’ Finally they did come out onto one of the balconies, just like royalty used to do.

“You could just hear the music. The crowd sat and listened to Paul McCartney sing ‘Till There Was You’’, one of the only soft slow numbers they did. The rest was just – loud. You couldn’t hear every note, but you knew it was The Beatles. No doubt about it.

Paul McCartney and John Lennon interviewed flying from Auckland to Australia

George Harrison and Ringo Starr interviewed flying from Auckland to Australia

“There was this young girl near us and she had a knitted hat with ringo on it and she threw it up on the stage. John Lennon flicked it up and threw it to Ringo and he caught it on his drumstick and popped it on his head. And this girl fainted. I’ll never forget that. She just passed out, she was rapt, it was all just too much. Here was Ringo with her hat on his head.”

Show over, The Beatles left the stage and – driven by a traffic cop with siren screaming – they were back in their hotel within three minutes.

"But we don't get blind or touch the drugs .." from NZ Truth, 30 June, 1964

Warned by the chaos that had occurred elsewhere in the country, the Christchurch police were better prepared. When The Beatles left Dunedin, the police took them on a route to the airport that was different to one published in the paper. In charge in Christchurch was George Twentyman, a police inspector later prominent during the Springbok tour. “We had a very flexible plan, but mainly to try and keep a distance between The Beatles and the young people,” he said. “Knowing they would go quite rampant if they were exposed too much to The Beatles, there had to be always quite a considerable space between The Beatles and the people, otherwise you’d have serious problems.” When The Beatles’ plane arrived in Christchurch, it was surrounded by police. A car at the bottom of the plane’s stairs whisked the group away while a crowd of 5000 watched at a distance.

The Beatles in Christchurch

The Beatles stayed at the Clarendon in central Christchurch, a grand old hotel where the Queen used to stay. Once again, female fans used the usual tactics to get inside to meet them, such as hiding in laundry baskets, but the mania was such that as The Beatles’ car got near the hotel, a 13-year-old girl lunged at the vehicle and was knocked down. She was taken inside the hotel and, for her trouble, got to meet The Beatles.

Twentyman described the female fans’ reaction to me. “Hysterical’s not the word, because when they’re hysterical they start crying. They were transported, I’d say, into ecstasy and excitement. Yet the boys, you could see it, they were trying to look as if they were, but they weren’t. The girls were screaming their heads off and carrying on. The girls just lost themselves.”

What made Christchurch different was a group of antagonistic males who stalked the band. Annoyed at all the attention The Beatles were getting from their Canterbury maidens, they threw a barrage of eggs at the hotel. A student also held up a placard that read: “We like Elvis, Cliff, Castro and Mao Tse-Tung but not The Beatles.”

The two concerts at the Majestic Theatre were once again reviewed for their novelty rather than their music. ‘Till There Was You’ was the only song one newspaper reviewer mentioned, preferring melodramatic reportage such as “… the shock waves reached danger level. The shrieking guitars, amplified through some fiendish electronic system, led the assault with Ringo’s drums filling in the gaps between blasts. The half-crazed audience did its best to scream and whistle above it all.” Some of the disgruntled boyfriends must have bought tickets, because among the usual jelly beans thrown at The Beatles, there were also marbles.

So it is understandable that The Beatles spent their last day in New Zealand in their Christchurch hotel rooms. When they left for the airport, the police – finally wise, but also a little mean-spirited – lined up outside the front door, where four cars waited. One limousine had its back door open, with a driver inside. It was another decoy: as 2000 fans gathered at the front door for The Beatles to appear, the police took the group out through a back entrance to another car.

At the airport that evening, another 2000 fans waited in the dark to bid them farewell. The runway had a brilliant, eerie glow thanks to the mercury vapour lamps used to light workers loading cargo for the Deep Freeze programme in Antarctica. A TEAL Electra taxied out; the distance from the public viewing platform and high wire fences to the plane was quite substantial, but still the police felt under pressure. Fifteen minutes before departure, The Beatles were driven onto the tarmac, and a boy ran towards the plane only to be grabbed by the police. The Beatles stood briefly on the plane’s steps for photographs and a wave, then boarded the plane to Sydney.

The Beatles’ only visit to New Zealand was almost over. As the Electra’s propellers warmed up, and the pilot was about to nudge the throttle, a policeman was heard to say, “If that bloody plane doesn’t go in the next few minutes, I’ll push it off myself.”

--

Read: The Beatles and New Zealand Music

Read: the story behind the large tiki given to the Beatles

A very thorough collection of links about the Beatles’ visit, compiled by Digital NZ.