“We resented the one way culture traffic into New Zealand…” - The Clean

We were living in the bottom flat of a two-storey concrete block on the east side of the Waikato River in the upper North Island city of Hamilton, my brother Gonzo, the Christian and I. Working and studying and obsessing about our favourite indie bands in a small inky, stencil-cut fanzine called Ha Ha Ha, which we’d drop in record shops in town and send to Ima Hitt in New Plymouth and Flying Nun Records to distribute.

The Clean, 1978, at Beneficiaries Hall, Dunedin. Doug Hood (vocals), David Kilgour (guitar), Peter Gutteridge (bass), Hamish Kilgour (drums) - Photo by Jeff Batts

I’d been corresponding with The Clean’s drummer Hamish Kilgour at Flying Nun HQ in Christchurch and he posted me a brightly screened poster announcing his new group, The Great Unwashed’s January 1984 Great Outdoors Tour. At the bottom, someone had written, “get to this gig guys and gals and we will have ourselves a hoedown.” Hamish, we supposed.

A grass roots tour of New Zealand? It was one of those overtly punk-political things the Kilgour brothers Hamish and David did. Punk had taken music back to the kids and the fans. They’d take it to the provincial cities and coastal towns. They were down to play Waihi Beach, Whangamata and Hamilton – all within easy reach.

It was at The Left Bank Theatre, an old black painted velvet carpeted theatre with balcony and chandelier on the Waikato River’s left bank, that we cornered them finally. The Great Unwashed had a minimal stage set-up which included the long open tube lamp later used as the cover photo on The Clean’s 1982 Great Sounds Great EP, which cast a bright hot orange-gold light over everything between it and the black walls and ceiling. Behind that, they propped three long rough wooden stakes in a skeleton teepee.

The Clean, 1978. Doug Hood on vocals - Photo by Jeff Batts

We took the prime spot up front at a white wrought iron table with youngest brother Stu as the house and balcony slowly filled around us. I was straight. No booze. Didn’t then. Lit up by the excitement because despite the new name this was The Clean – one of the great bands of the early 1980s indie boom – the line-up who had written the masterwork ‘Point That Thing (Somewhere Else)’.

The Kilgour brothers had been busy since the collapse of The Clean in late 1982. In mid-1983, they’d released (as The Great Unwashed) Clean Out Of Our Minds, a woodsy experimental album of naked acoustic and trippy psych. The Clean’s self-released classic offcuts and rarities tape Odditties also appeared in 1983, bringing to light a broader selection of sound and such indispensable songs as ‘Odditty’ and ‘At The Bottom’.

The Clean, Otago University, Dunedin 1981 - thanks to David Kilgour

Peter Gutteridge was the unknown factor. None of his post-Clean groups had endured and he had yet to contribute the three best tracks to The Great Unwashed recordings in Auckland the following week. Snapper wasn’t even in the air.

The Great Unwashed played three sets that night, 30 songs, including ‘Small Girl’, ‘Fish’, ‘Point That Thing’, ‘Slug Song’ and ‘Where You Should Be Now’. They were an acid instrumental outfit powered by surf and punk and Velvets drone and tempered by folk. It was the perfect sound for that blazing orange-lit gothic interior – two guitars and drums – with David Kilgour’s white Ibanez carving the air with none of the awkwardness of their lo-fi album recording. You couldn’t see the seams live. It was one long psychedelic splurge of folk rock jangle and out-there rockers.

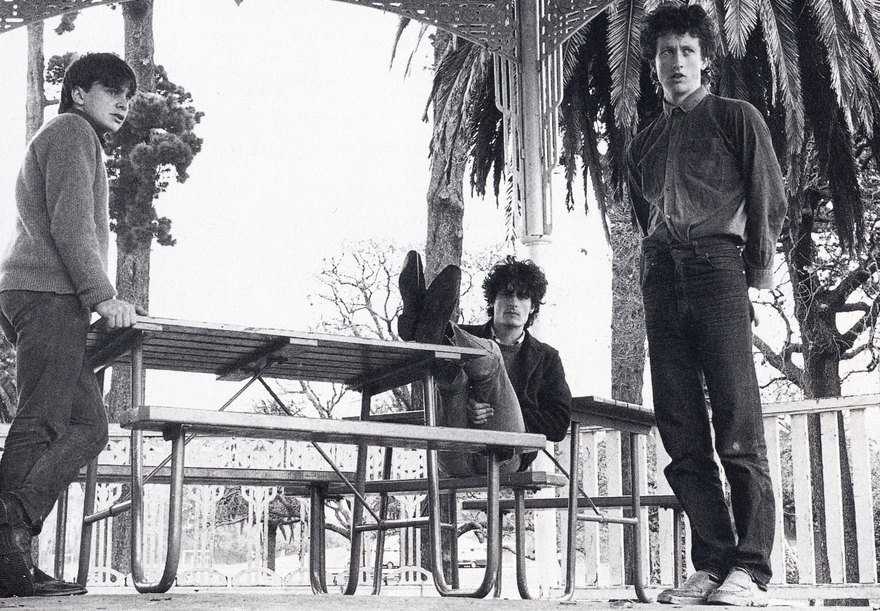

Hamish Kilgour, David Kilgour, Robert Scott, 1981

Afterwards, we surrounded a calm, wine drinking David Kilgour with questions flying. I wrote it up for the third issue of Ha Ha Ha (renamed Nebulous Reasons) that came out in March 1984. He had some questions for us as well and soon found out we were starting a band. We could have played before them, he said, which delighted and terrified us in equal measure.

Anything could happen

Meeting the Kilgour brothers in early 1984 was a first. We had all the new indie records, but my small town friends and I had never met the post-punk musicians who made them. But The Clean were different. They were punk-political thinkers who’d made it clear they wanted to engage with their audience and open doors to participation. Their interviews fair rippled with ideas for the way forward with norms often questioned and alternatives offered.

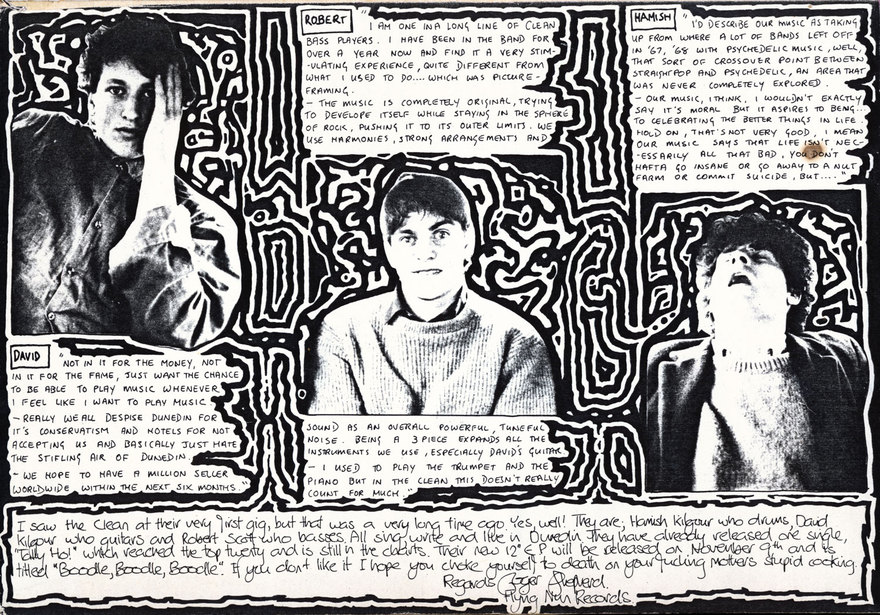

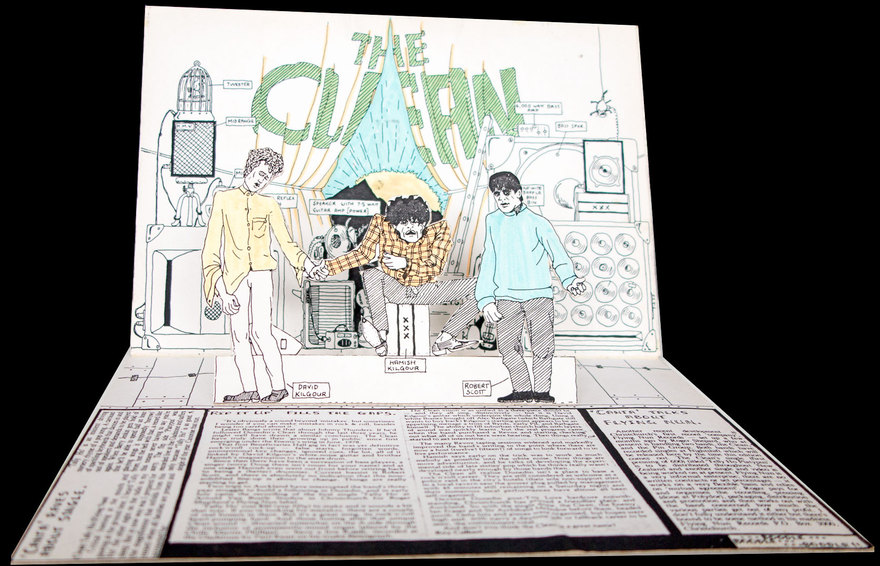

The back of the Boodle Boodle Boodle pop-up press kit, 1981 - Murray Cammick Collection

Like hundreds of New Zealand teens and post-teens, I found The Clean through the five song Boodle Boodle Boodle EP in late 1981. My brothers and I located it in Chelsea Records in the Centreplace mall in Hamilton and split the EP’s $4.99 asking price three ways. The playful, optimistic tone and Andy Shaw-filmed video of ‘Anything Could Happen’ had instant appeal. There was a lot of promise and freedom in its ringing open chords and allusive lyric. We found the EP had contrasting moods, just like the Velvets. The head-down acid instrumental ‘Point That Thing (Somewhere Else)’ brought the night. ‘Anything Could Happen’ brought the day. A distinctive Chris Knox pencilled sleeve with gold and black inner label and a band-generated comic booklet capped it off.

Recorded on Knox’s TEAC 4-track with Doug Hood in Auckland in September 1981, and released in November, Boodle Boodle Boodle stayed in the NZ Singles Chart for a full half a year, from November 1981 to May 1982. For the first 10 weeks it was in the Top 20. Despite its success, NZ commercial radio refused to play it. TV chart show Ready To Roll followed step, claiming they couldn’t play the video because radio wouldn’t play the song.

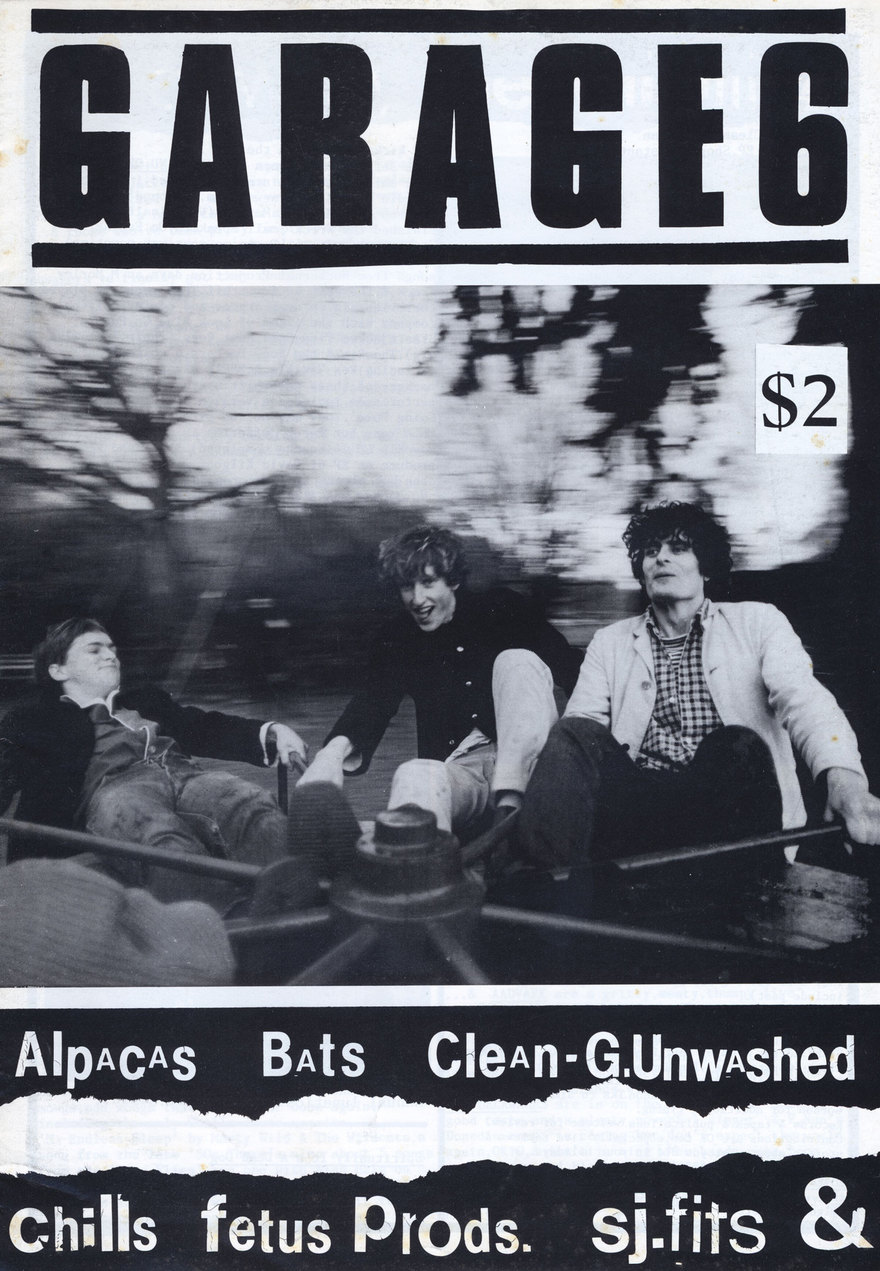

The Clean on the cover of Richard Langston's Garage 6

And as to the melange of sound and influence contained within? Hamish Kilgour told Garage fanzine in the mid-1980s “The Velvets were an influence, but that has been overstated. There was tons of stuff – west coast psychedelia, punk, post-punk, reggae, disco, sixties stuff … melody, songs with room for improvisation.” His brother David added, “Syd Barrett, Dylan, Beatles, Stones, Sex Pistols, Buzzcocks, Love, early Jefferson Airplane, New York Dolls, Stooges, Television, Gram Parsons, Jimi Hendrix, Byrds … ” All of which their new fans duly noted for future investigation.

Looking back at ‘Anything Could Happen’ in early 2012, Hamish remembered they were going for a “Highway 61/Rolling Stones country feel” born from a great affection for “20th Century folk, blues and country.”

Tally ho!

We’d been tracking The Clean through Rip It Up’s Dunedin rumours column as we did all the rising bands. It was a steady and reliable source of information extracted from local fans and writers that piqued interest and added much needed detail. In September 1981, The Clean’s first full Rip It Up feature appeared, titled Tally Ho!, and written by far south scene commentator Roy Colbert.

The Clean, Dunedin 1981 - Robert Scott, Hamish Kilgour and David Kilgour - Photo by Carol Tippett

“The Clean have truly done their growing up in public since first emerging under The Enemy’s wing in June 1978,” Colbert began, noting early days of “false starts, forgotten words, unintentional key changes, ignored cues, the lot,” linked by “David Kilgour’s white noise guitar and brother Hamish’s magnetism to the snare drum.”

“(David) Kilgour’s starting point appears to be an appetising ménage a trois of Byrds, early PiL and (Toy Love’s Alec) Bathgate himself,” he added, noting that The Clean had learned to fill halls with layers of sound and made real progress in their songwriting after they bought a Revox B77 2-track recorder in mid-November 1980.

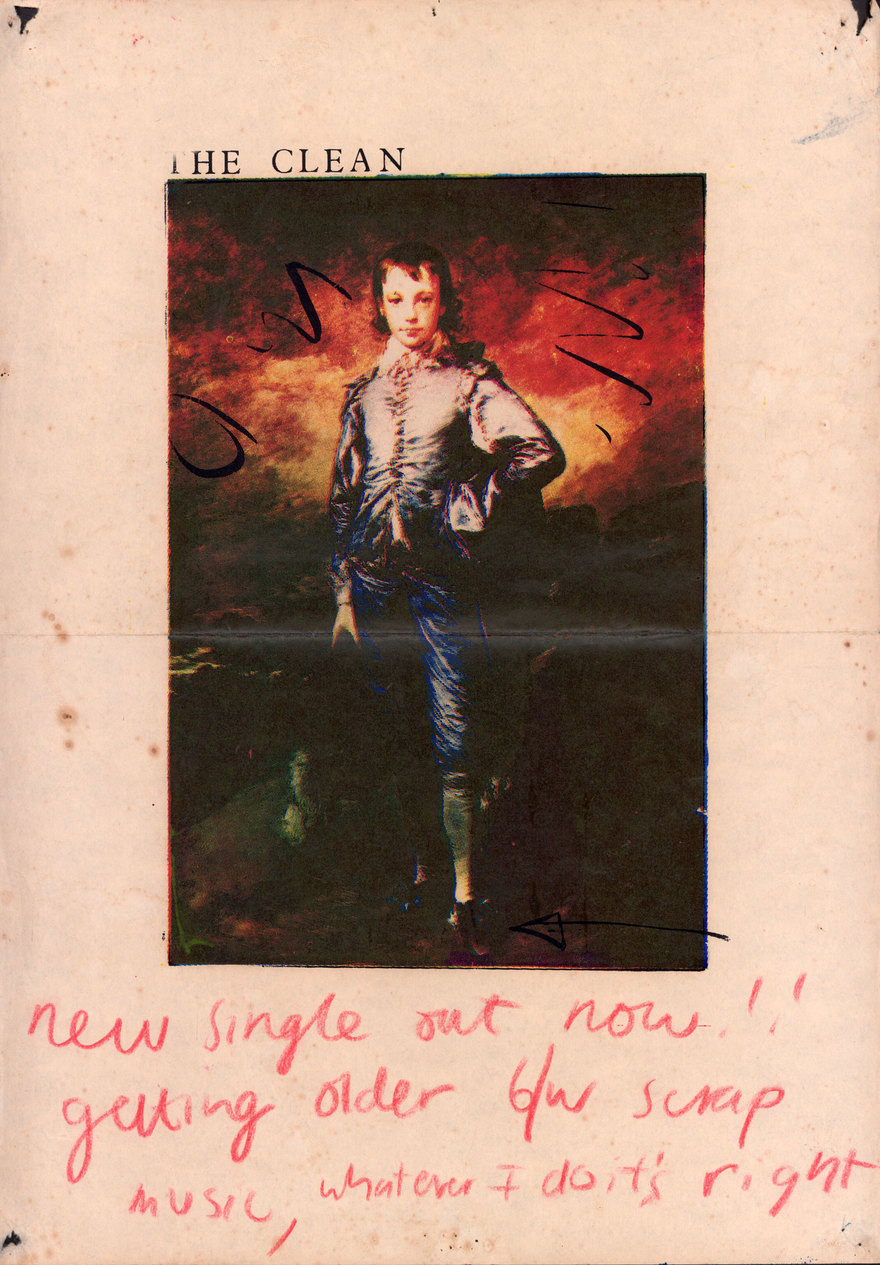

'Getting Older' poster, hand-written by Roger Shepherd - Andrew Schmidt Collection

The cultural politics came mainly from Hamish: “I think one of the most important things is getting our own musical identity – getting rid of our colonial mentality. Other New Zealand art forms like our films have been accepted overseas. There’s no reason why our records shouldn’t.”

If you needed a mission statement for the provincial indie scene of the 1980s, there it was. Clear, concise and highly relevant, these were ideas with a much discussed and mulled air about them.

The single, which the interview promoted, ‘Tally Ho!’ largely passed us by despite climbing to No.19 in the pop charts in September 1981. I can remember it peeking out from the basement wall in Tandy’s Victoria Street shop with an elaborate, silver graphic that sat strong against a pitch-black die cut sleeve. It was just one of many enduring and relevant indie records from New Zealand groups that year.

The sound was no great surprise either. The 1960s turn in NZ indie music had already happened. Toy Love and The Swingers successfully fished around in that particular pond. Auckland’s North Shore bands plus the Prime Movers and The Dabs were full of it. How Was The Air Up There? – NZ’s Nuggets – put 1960s psychedelic pop side by side with wild white R&B and weepy big ballads on release in 1979. The first two albums by The La De Da’s and Ray Columbus and The Invaders’ Anthology were in the shops again by early 1981. Christchurch groups were playing songs from Pebbles and other garage punk collections.

The original 1981 pop-up press release for Boodle Boodle Boodle. It was hand glued by the band.

What The Clean’s ‘Tally Ho!’ added was a very real freshness. Its chirpy, keyboard-driven hook (from The Chills’ Martin Phillipps) and happy gung-ho lyrics conveyed the sense of relief and mission that came in the weeks after the violent Springbok tour.

The Clean was already three years old in 1981. Their early years only leaked out sparingly in interviews in the decades to come. It was a surprise to find the Kilgour brothers had only recently moved to Dunedin from North Canterbury then Central Otago in the mid-1970s.

Talking to Simon Sweetman in January 2012, Hamish pointed to his early rural schooling as influential. “I had experienced radical young schoolteachers out of Christchurch in a small country high school at Cheviot in North Canterbury,” he remembered. “We had a cool art teacher, we did photography, sculptures for a small ceramic kiln and we’d be listening to radical socialist schoolteachers talking about Malthus, playing us ‘Revolution No.9’, digging Hendrix, Joe Cocker, The Who, The Stones, Led Zeppelin, The Byrds, Jim Morrison’s lyrics...”

“As a teen I devoured all of Jack Kerouac’s writing, went hitchhiking around New Zealand and hung out around the fringes and insides of Kiwi hippie, surf and glam counterculture.”

After university study in History and English at Otago University, he played briefly with The Enemy before forming The Clean with younger brother David in 1978. He was 22 and David still just 17. Early Dunedin shows with Doug Hood singing and David Kilgour’s high school friend Peter Gutteridge on bass displayed plenty of daring, but they were still finding their feet musically in Dunedin halls and at Christchurch and Invercargill shows with The Enemy in July and August 1978.

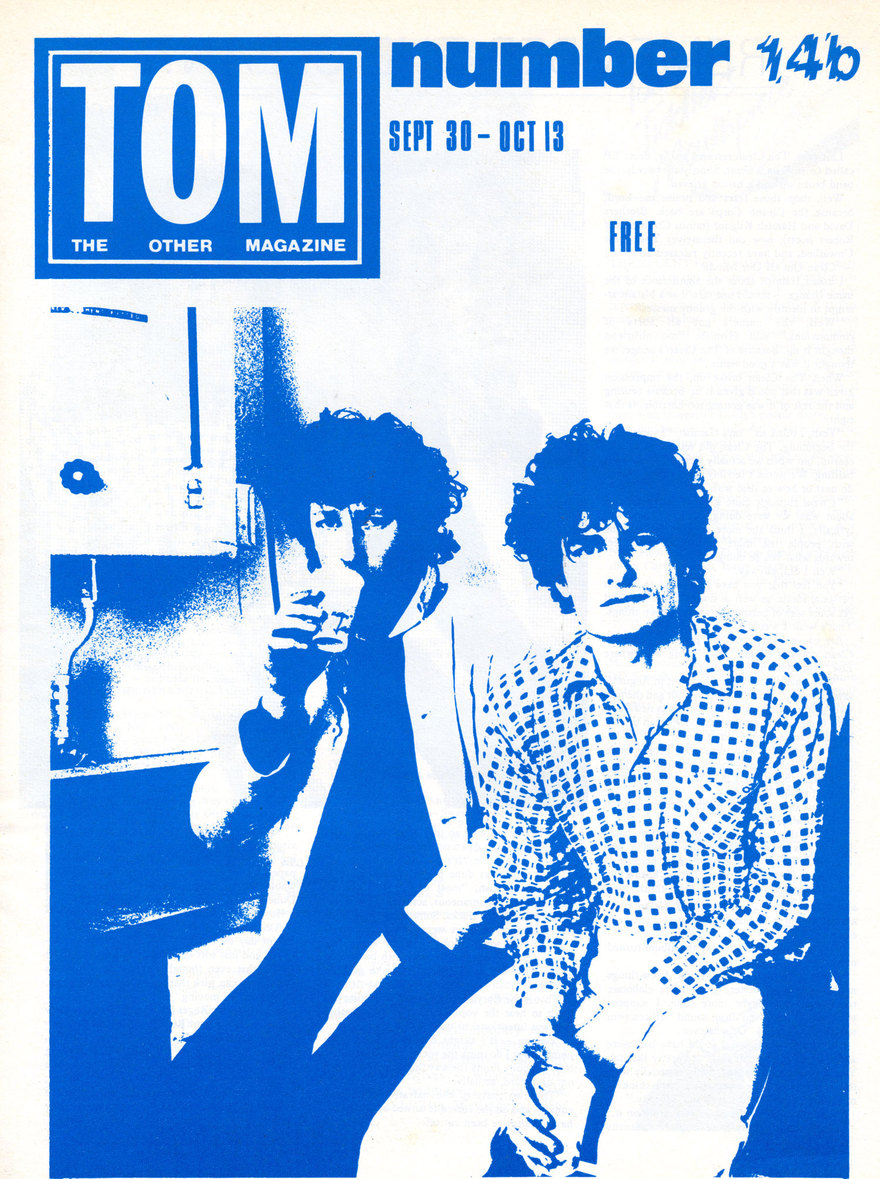

The Kilgour brothers on the cover of TOM, 1984, for The Great Unwashed

I’m in love (with these times)

The Clean hit an early peak in 1979 with the “really fast Buzzcocks/Saints guitar” of ‘Quickstep’, ‘I’m In Love (With These Times)’ and ‘Point That Thing’. That’s what Hamish told Garage’s Richard Langston in the mid-1980s. He briefly worked alongside the fanzine editor in 1978 as a Hunter S. Thompson-influenced trainee journalist at Dunedin’s Evening Star, under the guidance of Roy Colbert.

A new look Clean took those songs to Auckland in September 1979. Hamish Kilgour was up front singing, having relinquished the drum stool to Lyndsay Hooke, and Peter Gutteridge had departed to form The Cameras with Terry Moore (guitar) and Alan Haig (drums), leaving them without a bass player.

Auckland the first time proved frustrating. The Clean played just a handful of shows at Squeeze and Windsor Castle. With Hamish fronting and singing, they still lacked a regular bass player, despite trying many out, including Debbie Shadbolt and Jessica Walker (soon to form Shoes This High). An interview with Auckland Star’s Scene revealed all this and The Clean’s name’s origins in a surf movie character called Mr Clean.

David Kilgour returned to Dunedin in late 1979, where he briefly joined schoolboy punk group The Stains. Hamish stayed put in Auckland, fronting The SOBs with second-generation punks’ Michael Lawry, Pete Mesmer and Gary Hunt.

The SOBs survived into April 1980 when Hamish rejoined David and new bass player Robert Scott in a fresh-look Clean in Dunedin. The Clean’s second peak period had begun.

With Hamish drumming, The Clean linked up with teenage punks Bored Games and The Drones for a well-attended Coronation Hall show in May 1980. They were on the bill with Auckland post-punks The Features and Christchurch noiseniks The Gordons at Otago University in June for another big show, which was stopped by police for underage drinking.

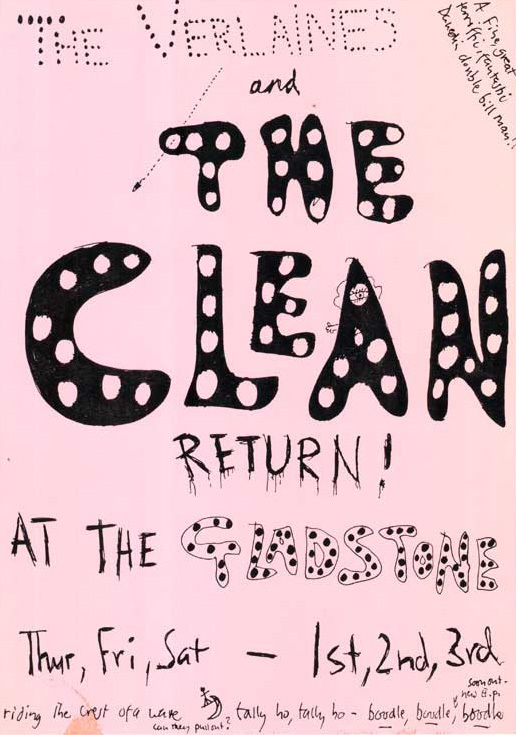

Partnering up with Heavenly Bodies, Bored Games, a touring Toy Love, The Same and The Chills for live outings at Dunedin halls, concert chambers and pubs, The Clean continued to perform and improve until late April 1981 when Christchurch’s DB Gladstone beckoned.

For many fans outside Dunedin this is where The Clean story truly begins. With Robert Scott adding musical chemistry and driven, folky originals, the group packed themselves into a newly purchased van with self-customised psychedelic interior and sound system, and headed north in April 1981 for their first genuine taste of popularity.

The Clean’s relationship with Dunedin had always been an awkward one – for Hamish in particular. He saw the southern city as narrow, conservative and violent. “Dunedin had a particular strain of Presbyterian stoic Scottish repression and conformity that spun into aggression, dogmatic moralism and drinking and drug abuse as the only license to be able to let go and be a bit free,” he recalled in 2012.

Now self sufficient with their own van and PA and an ever-growing swag of original songs, The Clean set their sights on the rest of New Zealand. Christchurch warmed to them quickly. The South Island’s biggest city already had a thriving post-punk scene that was serviced by responsive venues in the DB Gladstone and Hillsborough Tavern, and a little later, the Star & Garter Tavern. It was a music scene that record shop manager Roger Shepherd, who’d travelled south for shows by The Enemy, was determined to capture and make available on record through his embryonic indie, Flying Nun Records.

After a brief trip home, Auckland beckoned the trio again in late May 1981. An extended stay in the Queen City included shows at The Rumba Bar with The Screaming Meemees and a Battle of the Bands finals performance at Mainstreet. June dates with Tall Dwarfs, The Androidss and Smelly Feet followed at The Reverb Room and Rumba Bar.

The Clean were back in Christchurch for shows in early July with The Pin Group at the Gladstone and 3ZM’s Kool Sundays at Christchurch Town Hall. They also got ‘Tally Ho!’ down in a session at Nightshift studios. Previous attempts to make vinyl had failed when their instrumental ‘At The Bottom’ arrived too late for inclusion on Propeller Records’ new band compilation, Class of ’81. They also sent songs to Auckland DJ Barry Jenkin for airplay.

‘Tally Ho!’ was no surprise hit on release in September 1981. There was already a large, demonstrated appetite for the new sounds. Post-punk scenes existed in all the major cities and NZ (and overseas) indie records peppered what was then one of the world’s most adventurous pop charts.

The impact of ‘Tally Ho!’ was most likely strongest in Dunedin where The Clean found themselves at the centre of a circle of new groups. The band’s high school performances had been already been noted by youngsters like The Verlaines’ Graeme Downes, and new venues, including the low key Pandora’s Place in South Dunedin, were appearing.

Matthew Bannister, whose Sneaky Feelings would become one of the principal new groups, recounted a Pandora’s Place show by The Clean in his memoir, Positively George Street: A personal history of Sneaky Feelings and the Dunedin Sound (1999).

“(The Clean) were at their best at a short-lived venue called Pandora’s Place near the docks in Dunedin,” Bannister wrote. “The lighting set-up was unorthodox, the room being lit normally except for the band who were in an alcove, playing in darkness. I suppose this was the ultimate statement of invisibility. The sound, however, was huge, especially when David Kilgour switched on the reverb in the Gunn amp for ‘Point That Thing’. I found it hard to believe one guy could make so much sound. It was like the room was full of flying saucers.”

A more enduring home for the extrusion of southern indie sounds wasn’t long in coming. The Empire Tavern opened in mid-August 1981 for new groups with The Clean and The Verlaines the first to grace its slender stage. The following week, The Clean returned to Christchurch. By early September, they were in Auckland before taking in Hamilton and Wellington on the trip home.

In the capital, David McLennan cornered them for an interview for the city’s free music media monthly, In Touch, which ran in the magazine’s December issue. Hamish the thinker described their music as “taking up where a lot of bands left off in 1967, 1968 with psychedelic music. That sort of crossover point between straight pop and psychedelia – an area that was never completely explored.” And their future in music? David Kilgour saw it as “a long term thing, but on a casual basis.” Another typically prescient summation from the guitarist.

In November The Clean hit the highway to promote Boodle Boodle Boodle before gathering up the rising crop of Dunedin groups – The Verlaines, The Chills, The Stones and Sneaky Feelings – for a four-date stand at the Captain Cook in mid-December.

The Verlaines and The Clean at The Gladstone, 1982 - Christchurch City Library Collection

Great sounds great…

The Clean started the New Year quietly, sparking to life in February 1982 with an After Clash Party at Christchurch nightclub PJ’s, for those who had spent money on the petition to bring The Clash south. Another round of university orientation shows in Dunedin and Christchurch followed.

With their first EP still in the Top 40, The Clean headed to Christchurch in March 1982 to capture their second 12-inch EP with chief Flying Nun enablers Chris Knox and Doug Hood. To be called Great Sounds Great, Good Sounds Good, So-so Sounds So-so, Bad Sounds Bad, Rotten Sounds Rotten, it was their best collection yet. The Clean spent the rest of their time in the garden city with orientation and pub gigs, taking time out to head over the Southern Alps to the West Coast for the Nile River Festival.

In April, The Clean appeared on the cover of Rip It Up in a stark, shadowed black and white portrait. Inside, Rip It Up’s Christchurch correspondent Michael Higgins quizzed them on their “shambolic majesty”. There was talk about how being away from the centre gave them freedom, self-reliance and resilience from trends, and of potential fans in Europe and parts of America.

David: “But we’d probably be regarded as passé because we’re not futuristic and image wise and it wouldn’t help because we probably look like we’re just off the farm.”

And yet, more cultural politics from Hamish, railing against big PAs, lights and how drum rostrums elevated the drummer above the audience, with David adding, “Music is trying to talk to people on a human basis. We hate the concept of pop stars.”

Hamish: “It would be good to break down the whole ritualised behaviour pattern of the audience facing bands and getting pissed. The best thing would be to move away from hotels, but that’s difficult.”

On release in May 1982, Great Sounds Great… debuted at No.4 on the pop charts. This time there was a witty, bang-on video ready to roll, set in a bohemian coffee bar. The songs also sparkled. Despite some critical reviews, the EP is in retrospect a stronger and more consistent record than Boodle. ‘Beatnik’ is a fabulous keyboard driven pop song. ‘Slug Song’ mined similar territory while ‘Fish’ was a trademark Krautrock/psych instrumental, ‘Side On’ a biting Fall-ish riffer, and ‘End Of My Dream’, a thoughtful and persistent psych-folk tune.

The Clean returned to Auckland that month, playing packed shows at The Reverb Room and The Rumba Bar, the latter of which was filmed. Two long years on from their first abortive Auckland visit, they had returned with little left to prove. That’s when it all began to unravel. By June 1982, something was amiss and The Clean were strangely quiet.

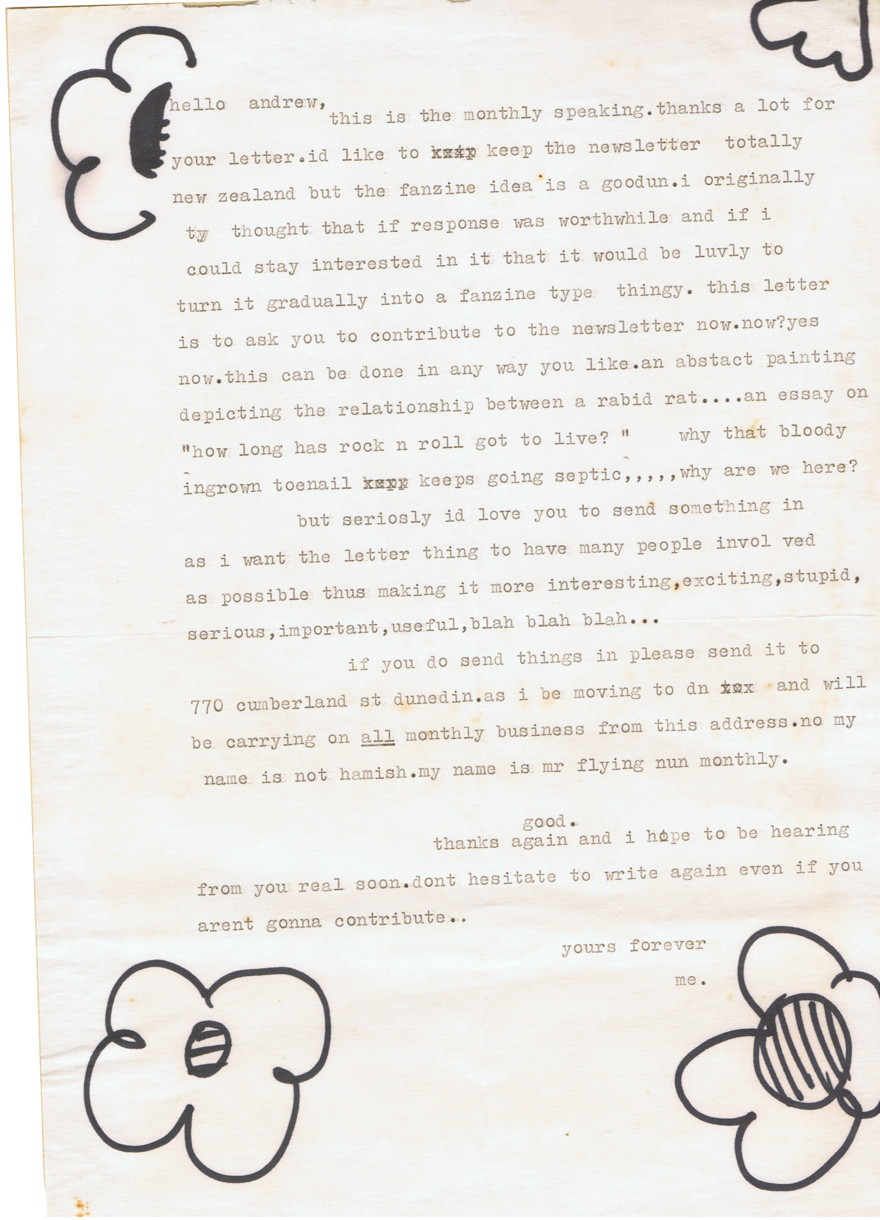

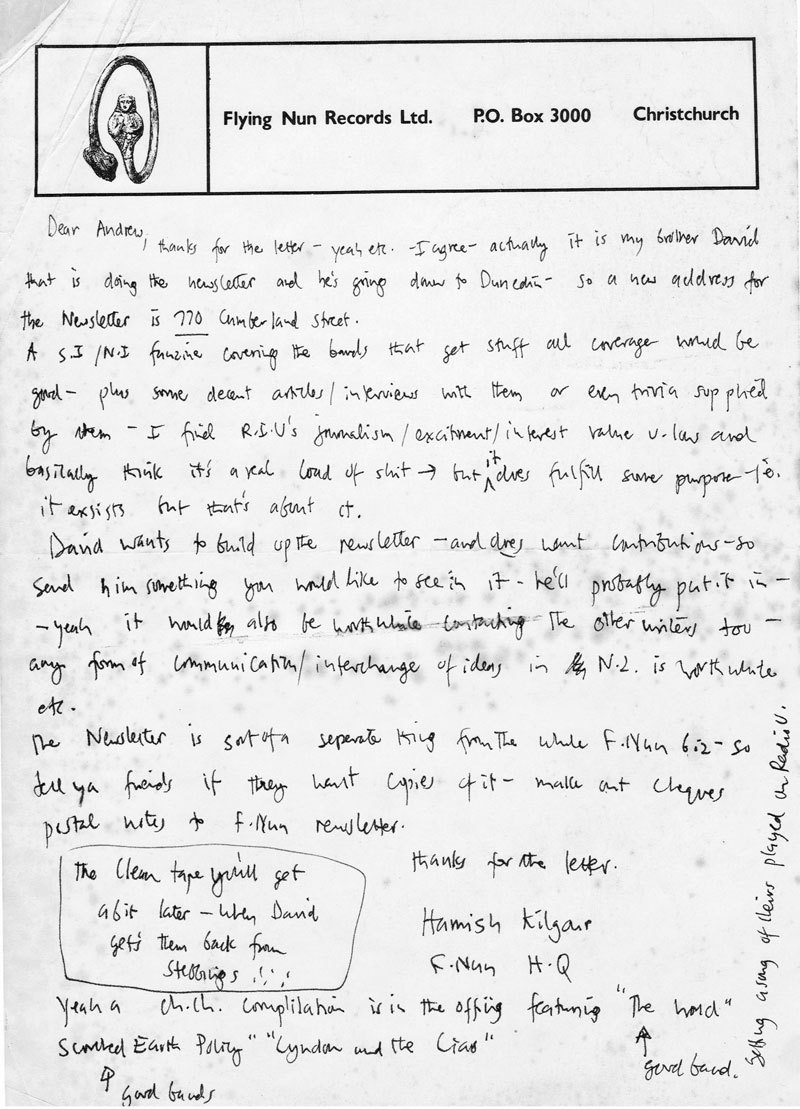

The letter from David Kilgour to Andrew Schmidt

Getting Older

In a state of semi-disbandment, The Clean rallied when offered Christchurch support slots before Mark E. Smith’s The Fall in mid-August 1982. They’d been asked to open for Teardrop Explodes in April, and turned them down, but the confrontational Fall were chart, fan and critic favourites in New Zealand, where their Northern UK provincial and indie roots struck a real chord.

Bootboy anger and ignorance marred The Clean’s set with spitting, abuse and thrown objects, forcing them and guest Martin Phillipps from the stage. Mark E. Smith, however, was impressed, giving them the thumbs up and comparing David Kilgour to Alex Chilton.

There would be one more record – the surging shambolic ‘Getting Older’, which wasn’t about the group, rather an annoying Dunedin scenester. Recorded with Knox and Hood in Auckland, the world weary/wise guitar pop gem seemed eternally on the verge of falling apart, but never quite did. It hardly dented the charts, staying barely three weeks and only making No.36 in October 1982. The Clean bowed for the second time in November 1982 with appearances at the Captain Cook Tavern in Dunedin with The Stones.

Clean out of our minds

It wasn’t unusual for groups to break up after two or three years in the early 1980s, even with substantial chart and live success. Early 1980s indie bands played more shows than later indie groups would and the charts were fickle. Even so, it felt like The Clean had short-changed us. Many young fans hadn’t had the opportunity to see them live. And what about that full songbook we’d been hearing about?

I was a regular buyer of mail order NZ indie records and tapes, dispatching letters and money with some frequency to groups and to Flying Nun Records, pestering them about future records. That’s how I first came in contact with Hamish Kilgour, who was living in Christchurch and working at Flying Nun Records. When the southern label announced a Flying Nun newsletter, I wrote to them and suggested doing a fanzine. Replies from David (the newsletter editor) in Dunedin complete with hand-drawn Warhol-ish flowers, and Hamish in Christchurch, were soon received.

When the first Ha Ha Ha appeared, Hamish’s response on Flying Nun’s letterhead was brimming with ideas and contact addresses. “Probably the first of its kind in New Zealand – it’s a real fanzine!!! Yeah!!!” he said. “Go for colour, photos etc!!!”

In July 1983, Odditties, a collection of 21 previously unreleased Clean songs, mostly recorded on the trio’s Revox B77, was made available by the group through Flying Nun. We flogged that tape to death, marvelling that The Clean’s songbook was extensive enough to relegate standout numbers such as ‘Odditty’, ‘Success Story’, ‘David Bowie’, ‘Mudchucker Blues’, ‘Hold On To The Rail’, ‘At The Bottom’, ‘In The Back’ and ‘Fats Domino’ to a retrospective tape, when they could have sat comfortably on any of the hit releases.

The Great Unwashed’s Clean Out Of Our Minds followed in September 1983. Clearly there was plenty of creative gas left in the Kilgour’s tank as songs such as ‘Small Girl’, ‘What U Should Be Now’, ‘Hold On To The Rail’, ‘Obscurity Blues’ and ‘Quickstep’ showed.

David Kilgour would remember the album as “really sloppy. It’s like its always falling apart but somehow keeps going. It was really immediate, just us waking up in the morning and recording. It’s like an extension of Odditites, the bedroom mentality.”

With Hamish living in Christchurch, Rip It Up reported his younger brother was playing in The Cartilage Family (with Peter Gutteridge) and jamming with David Pine and two members of The Blue Meanies (Andrew Brough’s first group). By year’s end, The Great Unwashed were playing out with Peter Gutteridge at Dunedin’s Oriental and Empire taverns. The Clean may have left the room, but they hadn’t left the building.

I Go Wild

Meanwhile, Robert Scott, whose songs had littered The Clean’s sets, was getting on with it. His Thanks To Llamas with Toy Love’s Paul Kean (bass) and Jane Walker (drums) evolved on Walker’s departure into The Bats, with Malcolm Grant drumming and Kaye Woodward on second guitar.

Before 1983 was out, Scott’s new group would have ‘I Go Wild’, a raw primal chunk of folk rock available on the Krypton Hits tape. In October 1984, it would be the key song on The Bats’ Top 40 EP By Night. Those early Bats songs have a ramshackle joy about them that still sounds fresh today.

The urge to inform and promote was still there as well. I was sending to Dunedin for Scott’s cartoon heavy fanzine Every Secret Thing and his compilation tapes of groups from the still rising Christchurch and Dunedin indie scenes such as Songs from The Lowland (1984) and Big Southern Hits (1984).

After leaving Hamilton in January 1984, The Great Unwashed headed up state highway one to Auckland, where they performed at Limbs studio and began recording their double 7-inch package, Singles, with Terry King at Progressive. Live, The Great Unwashed were an affirmation of The Clean's best sounds – head down acid instrumentals and rich folk rock. On record, they were thinner and more frantic, and the best songs were Gutteridge’s – ‘Born In The Wrong Time’, ‘Can’t Find Water’ and ‘Boat With No Ocean’ – which swung and stung with frantic ease – although David’s ‘Neck Of The Woods’ and Hamish’s ‘Duane Eddy’ weren’t to be sniffed at.

If sniffing was your game, you always drop a nostril onto Singles’ sewn plastic sleeve, made from the backdrop for ‘Neck Of The Woods’ video with it’s Jackson Pollock-styled dripped paint surface. Singles, a minor chart hit in May 1984, was re-released as a 12-inch EP format with a different sleeve.

In August, Rip It Up reported English DJ John Peel playing ‘Duane Eddy’ on his influential Radio One show, prompting Rough Trade Records in London to request 20 copies for sale. With Peter Gutteridge joining Hamish in Christchurch, The Great Unwashed expanded to a quartet with The Pin Group’s Ross Humphries, although no recordings were released with this line-up. By November 1984, David Kilgour had left the group indefinitely.

Interest in The Clean had yet to ebb away. ‘Point ‘That Thing (Somewhere Else)’ and ‘Billy Two’ from Boodle were placed on Australian compilation Beyond The Southern Cross in early 1985, and were described by NME as “excellent”.

We knew the Clean were world class, but it was always hard to judge their overseas profile. An extraordinary conversation between Rip It Up’s Russell Brown and REM’s Michael Stipe published in September 1984 gave NZ fans some indication of their wider worth and place.

“I’ve only heard the Clean, and what they became, The Great Unwashed – I liked them, The Clean were a good band,” Stipe said. When asked about common influences and musical similarities, he added. “It’s something I’ve thought about myself because places as far apart as New York and Dunedin and Glasgow and Brisbane, a lot of the people we meet seem to have the same musical heritage. I don’t know if its coincidence that most of those bands happen to be really good as well. Maybe its just being away from the centre that gives you a chance to develop independent of the vagaries of fashion and gives you a chance to experiment and seek out different forms of musical expression. But I don’t really know. Most of that music’s idiosyncratic, though, which is something I value.”

Letter from Hamish Kilgour to Andrew Schmidt

Live Dead Clean

New Zealanders maintained an appetite for the group. Live Dead Clean, an EP that collected up live recordings from shows in Auckland and Christchurch in 1981 and 1982 spent five weeks in the charts rising as high as No.23 in August 1986.

The EP title, a cheeky reference to an early Grateful Dead album, showed that The Clean’s insight and humour was still intact. Nor was their songbook depleted, as three of their final compositions’ ‘Caveman’, ‘Two Fat Sisters’ and ‘At The Bottom’ showed.

When Richard Langston’s Garage fanzine emerged from Dunedin in 1984, it was thick with unique history on the trio, particularly the last three issues, one of which had The Clean on the cover. “Safety pin folk, psychedelia, home made rock n roll,” Langston called the music, offering the opinion of “what set them apart was this weird strain of folk. Perhaps the country’s most indigenous pop ever.”

My brother Stu and I were living in Dunedin by then, drawn south by the Celtic city’s musical allure, a good part of which The Clean provided. We caught David Kilgour at arts venue Chippendale House in Stafford Street with a pick up band, including Michael Morley (The Dead C) on keyboards. After a hesitant start with The Clean’s ‘Filling A Hole’, Kilgour left the stage and didn’t return. The following year, he’d have new trio Stephen up and functioning.

Back in Christchurch, Hamish and Ross Humphries had Blue Dolphins (Twin Guitar Orchestra) with drums, cello and flute. He’d soon be drumming with Nelsh Bailter Space on their brilliant debut EP and album. Peter Gutteridge also found firm ground with Snapper while Robert Scott’s The Bats were already well established.

In 1986, Flying Nun Records collected up The Clean’s early records on Compilation, which was released in NZ, Australia, Europe and the UK, where it sold in excess of 7,000 copies. Compilation was released in the USA in 1988 on Homestead Records with six extra live tracks. A second Odditties tape in 1988 gathered up the remaining odds and sods from The Clean and The Great Unwashed.

Which would have been a good place to end it, but The Clean were about to find one hell of a second wind.

–

For part two of The Clean story, please go here.