The York Street Neve desk in 2014

York Street arrived in 1992 and immediately took its place as Auckland’s premier recording studio. It was originally associated with the big rock sound of Shihad and The Feelers, though it has also been used by indie acts, pop stars, and even orchestras. Yet its location in Parnell meant that the land's value gradually began to far outweigh the slender profits it was making. In 2014, the owner decided to shut down the premises.

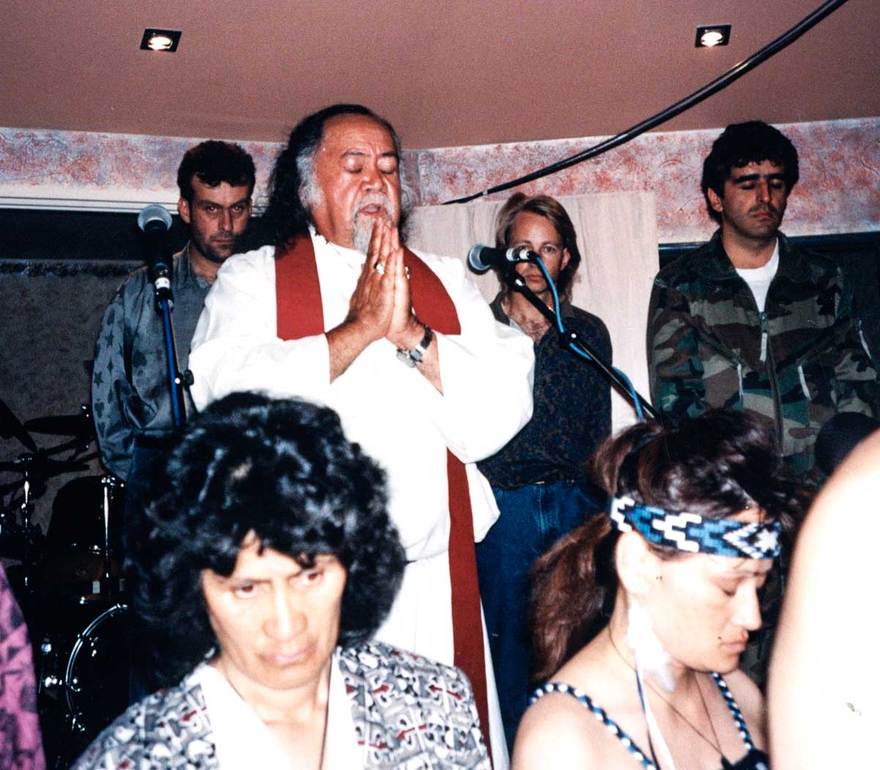

Jaz Coleman, Martin Williams and Malcolm Welsford at the opening of York Street, 1993

York Street was started by three men, who each had a depth of experience in music – sound engineers Malcom Welsford and Martin Williams, along with UK expat post-punk musician, Jaz Coleman. Welsford was best known for the work he’d done at Marmalade studios in Wellington, while Williams ran Last Laugh Studios in Vulcan Lane, Auckland (a relatively small space that could only be reached via a set of near-vertical stairs). The pair met when they were asked to mix the DVS single, ‘Big Love’, at Airforce Studios and, after getting to know each other further, they came up with the idea of starting a studio together.

In 1992, Williams and Welsford began searching for a new space that would suit being turned into a studio and their project reached the ears of Jaz Coleman. Not only was he the frontman of famous UK post-punk group Killing Joke, he had produced five out of eight of their albums at that point (as well as albums by Art of Noise and The Mission). He brought both solid financial backing and a level of gravitas to the project, but it still proved difficult to find the right premises. Finally, a rental agent took Williams to a large brick and concrete building in Parnell that had once been a car factory. After months of searching, the final location turned out to just over the back fence from Williams’ own house.

The space ...

Construction begins

The control room during construction with Malcolm Welsford coming up for air and Steve Kennedy on the right

Malcolm during construction, 1992

The creation of York Street

The interior space of the building was huge and they decided that the bare brick should be left showing to provide a sturdy feel to the surroundings. The set-up of the main studio was designed by Steve Kennedy (from Big Noise Productions) and featured a massive central space (20m high ceilings and an overall space of 93m²) with vocal booths at one end and the control room at the other. The team also installed kitchen, dining, and lounge facilities in a separate section so musicians could feel at home.

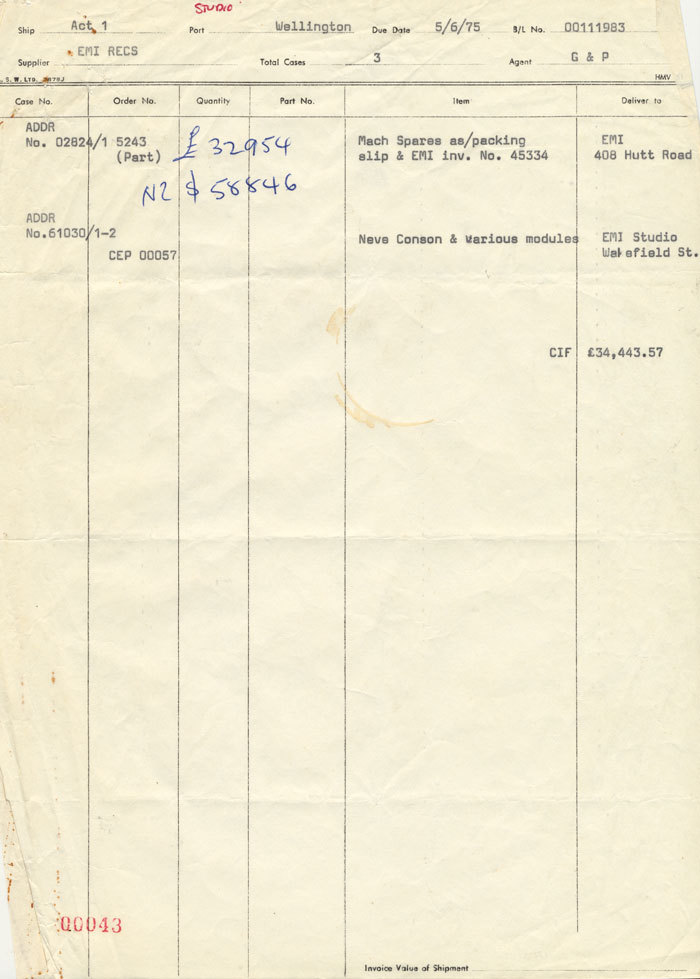

The studio’s crowning glory was a mixing desk designed by legendary engineer, Rupert Neve (whose work had been honoured with a Lifetime Achievement Technical Grammy Award in 1989). York Street’s Neve console spent the first nine months of its working life at the legendary Abbey Rd Studios in England, before being shipped to the EMI studio in Wellington in 1975. It was eventually purchased by a Christian Fellowship group, who had it set up in a house in Johnsonville. Welsford used it in the EMI days and was excited when Williams told him that it was up for sale. The pair drove to Wellington to see it and found that an American company had already offered $20,000 for it. The bidding was fierce, but eventually the team from York Street won out.

The Neve desk at York Street in the mid-1990s

The original 1975 shipping invoice for the Neve desk

The first album to be recorded at York Street was the debut by Shihad, Churn, with Jaz Coleman on the controls. His production leaned heavily toward the industrial metal popular at the time, but more importantly the drum sound on the album set a new standard for rock music in New Zealand. This factor in particular would see Shihad returning again and again to York Street for successive albums. Next up was the even more successful debut album by Supergroove, with production duties shared between Welsford and the band’s lead singer, Karl Steven. These two success stories set the idea in people’s minds that if you wanted to create a professional rock album, then York Street was the place to record it.

Malcolm and Jaz recording Shihad

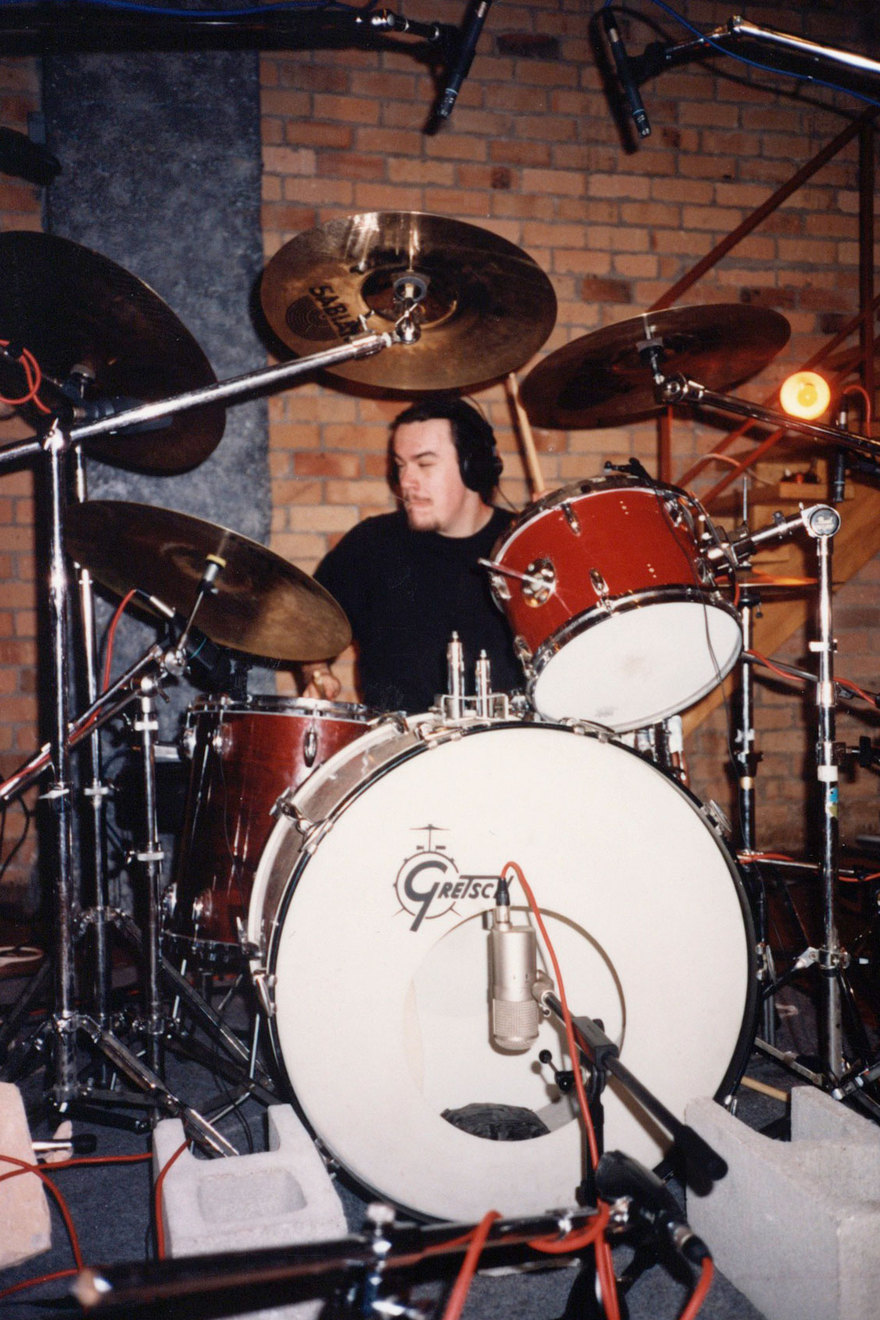

Shihad's Tom Larkin recording at York Street

Shihad's Jon Toogood at York Street during the Churn sessions

According to Welsford, the heart of the studio’s success couldn’t just be put down to its professional set-up. “The success of the studio just came from hard work. We did a lot of long hours in the studio – me and the bands I was recording – and that’s how we produced great sounding albums.

Coleman departs, York Street One and Two are born

Two years after opening, Williams and Welsford bought out Coleman’s share. By this stage, York Street was already beginning to be seen as a facility for only top end musical acts, though by world standards its fees were relatively cheap – and its rates were similar to the former best-place-in-town-to-record, Harlequin Studios. In 1995, a second branch of York Street was set up in central Auckland to cater to cheaper end of the market (competing against The Lab and Ground Zero), though Welsford admits he was driven by another motive. “I’d always loved the old TVNZ building on Shortland Street, that was the main reason we set up a studio there.”

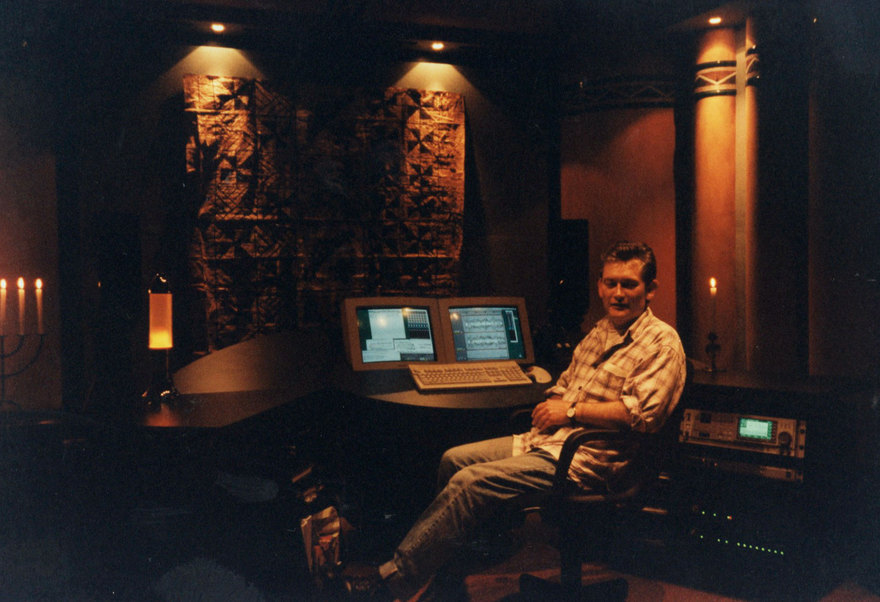

Steve Kennedy at York Street's mastering suite in the old TVNZ studios in Shortland Street. Kennedy, a producer / engineer with a list of credits that includes countless iconic New Zealand recordings, was part of the York Street story from the very beginning.

This meant bands could record drums in Studio One, then finish the other parts more cheaply in Studio Two. It provided a link to the indie scene and many of 95bFM’s live-to-air recordings around this time were broadcast out of here. A year later, a third space was opened, which could be used for mastering and this meant bands could now avoid having to fly to Australia (or further) to professionally master their recordings.

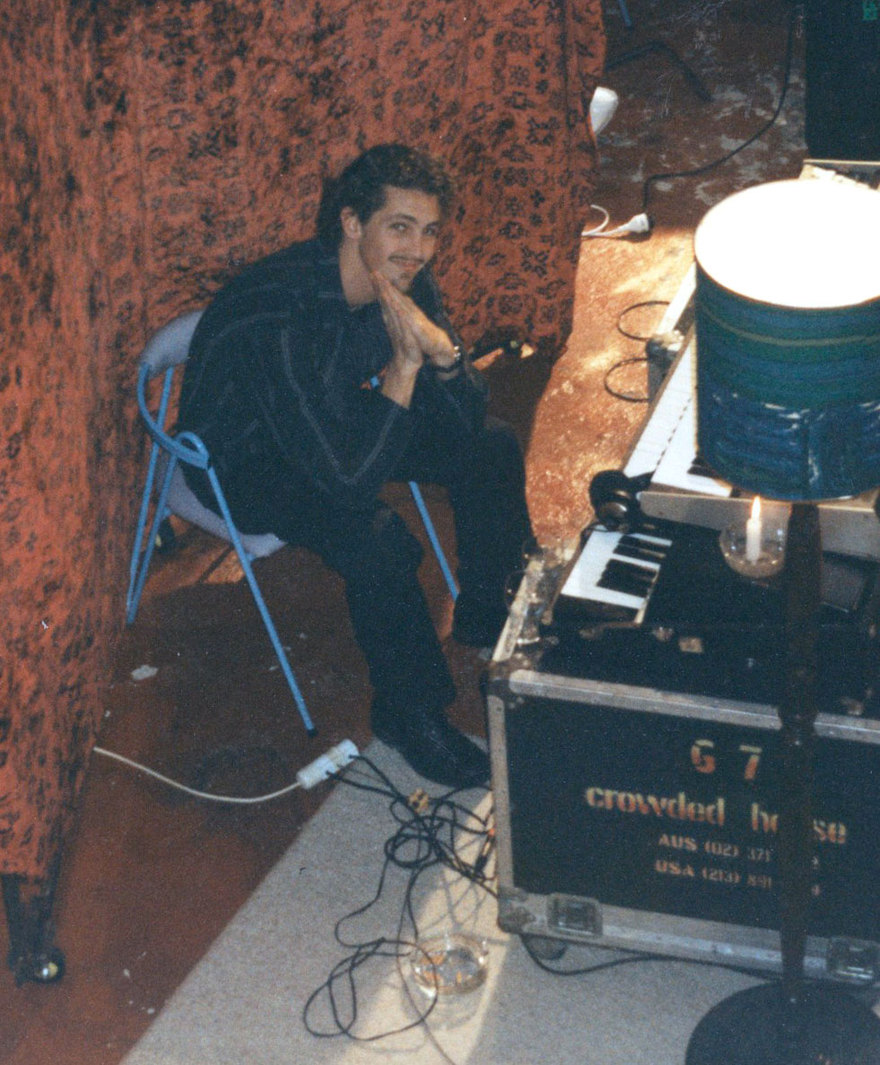

These changes expanded the range of bands that worked within York Street. The next couple of years would see a wide range of people record at the studio, from the most indie of musical acts – Superette and Bailterspace – through to the country’s most successful acts, Bic Runga (who recorded her first single, ‘Drive’, at the studio) and Crowded House (who recorded three tracks there for their compilation, Recurring Dream, 1996).

Crowded House at York Street

In 1998, York Street unintentionally provided support to dozens of young Auckland bands, when their premises were booked out by two badly organised young entrepreneurs, looking to create a compilation album. However, the pair didn’t have the money to pay for the sessions, so Williams and Welsford offered a compromise to the bands involved – the studio would release the compilation directly. This led to Keen As (1998), which captured a number of new bands in their infancy – from Trinket (who went on to be The Datsuns) to Tadpole to Steve Abel.

Supergroove at York Street

Supergroove's Joe Lonie at York Street

Supergroove's Nick Atkinson

Supergroove

Up to this point, the studio was still primarily based around analogue technology and even the loops that Welsford had recorded on Shihad’s ‘Deb’s Night Out’ were done by splicing sections of tape together. Welsford was a big believer in capturing live musicians to tape, though the studio also had digital recording software available. In fact, one of the most successful albums to come out of the studio over this period was The Feelers’ Supersystem (1998), which mixed a huge rock sound with hints of electronica (courtesy of beats created by Paddy Free). Nonetheless, the hallmark of the York Street sound was massive drums, with thick layers of heavily produced guitars. In essence, York Street was known as a studio for modern rock bands who wanted to create professional, full-sounding rock hits. Welsford isn’t surprised that it gained this reputation. “It just reflected the music that I liked at the time and the bands I wanted to work with.”

The end of the first era

A huge change hit York Street just as the New Millennium was dawning. The studio was about to lose Welsford, despite the fact that his name had become synonymous with its output. His own relationship with his fellow co-owner Martin Williams had deteriorated over the years and, these days, Welsford doesn’t have a kind word to say about him or about previous partner, Jaz Coleman.

Malcolm Welsford at the Neve in 1994

Williams apparently held Welsford in similarly low regard. This led to an acrimonious split and Welsford put his focus into other work – he created Karekare Studio and then a second studio on Dominion Road. In 2005, Welsford moved to Hollywood and began looking for new artists to develop. His most lucrative work was producing tracks with Adam Lambert before the singer managed to breakthrough to widespread success by coming second on American Idol. After Lambert’s success, the early recordings that Welsford produced were released as the unofficial album, Take One (2009), which sold 48,000 units. However, it took three years of legal battles with Sony before Welsford finally profited from these sales. He moved back to New Zealand in 2012, which is where he currently lives and works.

Martin Williams

The New Millennium

The new owner of York Street was Adrien de Croy, who was also the man behind a breakthrough piece of internet software (Wingate) in the mid-90s. Mutual friends had introduced him to Jeremy McPike, who was a lecturer at SAE (Auckland’s School of Audio Engineering). McPike had a great deal of knowledge about recording technology and was given his first job at SAE immediately after graduating from the institution with near-perfect marks.

McPike and de Croy began discussing the idea of starting a new studio, but McPike found that his new friend’s aspirations had run ahead of his own: “He ended up going a bit overboard and buying York Street! The people who were lined up to buy it were going to knock it down and build apartments. Adrien paid probably twice what York Street was worth, because he didn’t want that to happen. He’s just a kind person basically and really wanted to contribute to local music. He saved York Street without a doubt and that’s a fact that should be more widely known.”

Shihad's Tom Larkin and Sony Music's Malcolm Black at York Street

McPike was appointed studio manager and decided that his first aim should be to open up the studio to a new range of bands. “When I was at SAE, York Street was seen as this really scary, huge place where famous people recorded and I was very intimidated and so I made it our goal for York Street to be known as a very friendly place to work and a nice place to be around.”

Over the following decade, York Street was the home to an even more impressive run of hit records, including albums by Fur Patrol, Elemeno P, Tadpole, Brooke Fraser, and Pluto. Not surprisingly, it was also used by a number of bands on de Croy’s own label, Siren Records – both Goldenhorse and Opshop recorded some of their biggest selling records at the studio.

Many young, heavy acts also sought to seek time in the studio, even if it was only a few days to capture some thunderous drum sounds before they retired to a cheaper studio to record guitars and vocals. This explains the run of punk and metal acts that went through the doors, which includes Kitsch, Blindspott, 8 Foot Sativa, The Bleeders, and Sommerset.

Even more recently, York Street has continued to provide a recording space for some of New Zealand’s most successful acts. Katchafire used the studio to record the majority of their album, Say What You're Thinking (2007) and Midnight Youth used it for their second album, World Comes Calling (2011). Both of these albums had been supported by NZ On Air’s “Phase Four” album funding scheme, as had dozens of other albums previously recorded at York Street, but this funding scheme came to an end in December 2010. Yet, such was the reputation of the studio that it kept on being used at a high occupancy rate (McPike estimates it was booked around 95% of the time over these final years). Nor did it ever need to rely on doing post-production work to survive – it was a home for bands recording albums and seldom delved into other areas. One of the most high profile pieces of work that was completed during the final years of the studio was the recording of all the music used for the opening ceremony of the Rugby World Cup.

Clint Murphy, Jamie Exiter, Simon Gooding, Justin Maudsley, Chris Winchcombe (mastering engineer) and, in front, Jeremy Mcpike, 2014

The main room of York Street in 2014

The doors finally close

Nonetheless, things had changed for Adrien de Croy over the previous decade and a half. He was now settled down with a family and was acutely aware of the large amount of money that he tied up in the building that York Street was housed in. In 2014, he finally decided to sell up and draw down his money. McPike wasn’t surprised by this decision: “It isn’t about York Street closing because it isn’t well run. The building is just too expensive. The only reason we’re not moving to another building is because the relocation costs would be massive.”

Jeremy Mcpike

It turned out to be a nice coincidence that one of the last acts to book the studio was Shihad, who’d organised for Jaz Coleman to produce their next album – effectively winding the clock back two decades to when the studio first began. McPike bought the brand name “York Street” and all of its equipment, but initially decided to put this aside for the time being and accepted a new job at Neil Finn’s state-of-the-art Roundhead Studios. McPike believes his new workplace will be an equally inspiring place to create music: "Neil has has made a significant commitment in building this beautiful place to make music, and I really hope that the NZ music community will continue to support this world-class facility."

At the York Street farewell, 21 April 2014: Martyn Alexander, Chris Winchcombe, Gavin Botica - Photo by Karsten Schwardt

Despite having to close up shop, McPike has very fond memories of his time at York Street. “I hope it’s remembered as friendly place, where clients soon became friends and where attention to detail was always held as important. Over the years that I ran the studio, we also had around a dozen unpaid interns, who all went on to some of the most well respected sound engineers in New Zealand. So York Street was a training ground and I’m really proud of that too.”

The blessing and lifting of tapu at the official opening of York Street Studios in 1993. The original partners are behind - Martin Williams, Malcolm Welsford and Jaz Coleman.