Mention music and Invercargill and – Keith Richards’s slur notwithstanding – a rich tradition comes to mind. Many have been honoured in recent years by the Southland Rock’n’Roll Hall of Fame: Jimmy Hill and Wally Scott of the Invaders, Dave Hogan of The Unknown Blues, Dave Kennedy of Link, Murray Burns of Mi-Sex, Jason Kerrison of Opshop. In country music, legendary steel guitarist Les Thomas, and singers Suzanne Prentice and Kylie Harris.

A piano arrangement of Alex Lithgow’s ‘Invercargill March’ (download link below). - National Library of New Zealand.

But for over a century, a piece of music written in tribute to Invercargill – by a composer who spent his childhood there – has been a perennial hit, around the world. After ‘On the Ball’, it was the next biggest hit associated with New Zealand.

Written in 1908, Alex Lithgow’s ‘Invercargill March’ is still known and played worldwide; it remains one of the most famous pieces in the international brass band repertoire. Shortly after it was written, it quickly became a standard for bands; as early as 1913 – and perhaps even 1911 – it was recorded by the New York Military Band, and released on an Edison cylinder.

A 1913 recording – on an Edison cylinder – of the ‘Invercargill March’, performed by the New York Military Band.

The popularity of the ‘Invercargill March’ intensified in 1915 during the Gallipoli campaign. Anzac troops, weary from fighting at the front, often asked their band to play the piece when they marched back to camp. At Anzac Cove the bandsmen knew the piece so well they didn’t need to see the music, and could play it in the dark, a veteran musician told New Zealand brass band historian Stanley Newcomb. “To these men ‘Invercargill’ was more than just a march – it inspired patriotism, built up their morale and above all, was a national tune which they all knew and loved so much.”

An Otago Regimental Band performing in the transport lines under trees near Louvencourt, France during World War I. Photograph taken 20 April 1918 by Henry Armytage Sanders. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, ref: 1/2-013146-G.

Lithgow, the composer of the ‘Invercargill March’, was sometimes called “the Sousa of the Antipodes”. The two composers were contemporaries but while the internationally famous American bandmaster was an extroverted showman, Lithgow was more reserved, and happy working and living in the musical backwater of Launceston, Tasmania. (John Philip Sousa and his 60-piece band performed in Launceston in 1911, but it is unknown whether the band master met Lithgow. Sousa reportedly referred to the ‘Invercargill March’ as a masterpiece, and occasionally included it and other Lithgow works in his band’s concert repertoire.)

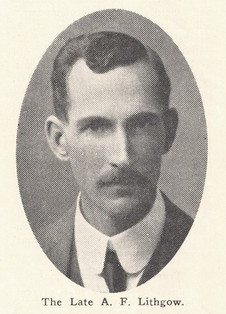

Alex F. Lithgow, composer, who died in 1929. Band musicians often nickname his most famous piece, ‘In for a Gargle’. Photo courtesy John Whiteoak.

Alexander Frame Lithgow was born in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1870, the son of a tinsmith who also repaired musical instruments. The family immigrated to New Zealand when Alexander was six, and he attended Invercargill Grammar School. His father gave him his first music lessons when he was nine, and he performed with his siblings as the Lithgow Concert Company (his brother Sam could play the piano and cornet simultaneously).

In his teens, Lithgow became a renowned cornettist. He was invited to join the Invercargill Garrison Band at 11, and by 16 he was the band’s principal cornet soloist, winning competitions in New Zealand and Australia. Between 1890 and 1893, Lithgow won the soloist’s prize three times at the annual contests of the United Brass Band Association of New Zealand, receiving a solid gold medal each time.

The exquisite tone he achieved with his cornet led him to be nicknamed “the Bellbird”. He believed that when practising, musicians should think about the music for 10 minutes, and then practice it for five. Also, that three hours practice a day was needed for those who wanted to become champions.

The ‘Invercargill March’ as played on a pianola.

Lithgow was also involved in many musical groups while growing up; he played cornet to accompany the Invercargill Choral Union, and violin in dance bands that played at balls across Southland, travelling by train before returning to Invercargill the next morning.

‘Land of the Moa March’ by Alex F Lithgow (download link below). - National Library of New Zealand.

His first published composition was ‘Wairoa’. When he was about 17, he took the piece to band practice, and the conductor chose to play it at a regatta on board the steamer Wairoa. The captain of the ship enjoyed the march and asked what it was called. When he was told that one of the young musicians had written the piece, and that it had no name, the captain said, “Well it has now: ‘Wairoa’.” To celebrate, he invited the band for a drink. “By nightfall, the march had been played many times,” wrote Newcombe, “and young Alex remained the only sober member of the band.”

Lithgow was briefly a member of the Woolston Brass Band, just prior to leaving New Zealand in 1894 to become the conductor of the St Joseph Band in Launceston, Tasmania. He also led the Launceston City and 12th Battalion Bands.

Despite being based in Australia for the rest of his life, Lithgow’s compositions often reflected his lasting connection with New Zealand. He gave his marches titles such as ‘Wairoa’, ‘Sons of New Zealand’, ‘Land of the Moa’ and ‘The Southlanders’ – as well as ‘The Wallabies’, ‘Boomerang’, ‘Victoria’ and ‘Sons of Australia’.

The ‘Invercargill March’ recorded by the Band of the Royal Air Force on the Columbia label.

After an early performance at Bathurst, NSW, the ‘Invercargill March’ first came to prominence in November 1909, when Lithgow sent the piece to the Invercargill Garrison Band. His brother Thomas was the conductor, and they were about to perform in a national bands’ contest in Christchurch. Lithgow dedicated the march to his birthplace, “Invercargill, the Southernmost City in New Zealand (End of the World), and its Citizens … as a memento of the many pleasant years spent there in my boyhood.”

The ‘Invercargill March’ – a recent performance by the Band of the Royal Regiment of New Zealand Artillery.

In the next few years ‘Invercargill’ achieved worldwide fame through “familiarity, publication in the United States of America and the First World War”. Newcomb doubted that any tune had brought such fame to a single city. Lithgow was known to call the piece “blessed Invercargill”, exasperated that he had written so many other works that received little attention, yet he considered them superior. Among his many New Zealand-themed marches were ‘Rauparaha’, ‘Haere Mai’ and ‘Kia Ora’.

Lithgow published his own compositions using the imprint Commonwealth until 1913, after which he was represented by Paling’s. Already, several of his works had been published in pirate editions in the USA. He received royalties for most of his music, but he wasn’t driven by the desire to make money. “I simply have to write marches, for two reasons,” he wrote in 1918. “They sell best and take least time.”

The ‘Invercargill March’ on Tanza 78rpm disc #Z281, recorded by the Wellington Institute Senior Silver Band.

Other patriotic marches written by Lithgow during the First World War include ‘Gallipoli’ – which he sold to Paling’s in July 1915 for £2/10/0 – and ‘Pozieres’, named after a village at the centre of the Battle of the Somme.

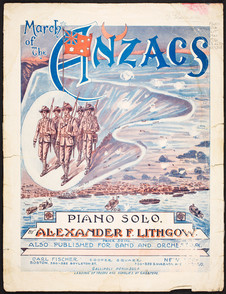

On 21 December 1918, six weeks after the Armistice was signed, the Second Battalion Otago Band crossed the Rhine at midnight by marching over a pontoon bridge, performing the ‘Invercargill March’. Also popular during the war were ‘The Southlanders’ (sometimes called ‘8th Regiment’), ‘Sons of Australia’ and, in 1916, ‘March of the Anzacs’. Described as a “sprightly march”, the cover of ‘March of the Anzacs’ depicts “the landing of troops and supplies at Kabateple” – an early portrayal of New Zealand soldiers at the front.

Lithgow wrote approximately 200 marches, as well as pieces for band, orchestra, piano and voice. In 1916, Metronome magazine described the appeal that Lithgow’s compositions had for bandsmen: “There is an irresistible catchiness in his melodies and a maximum amount of effect generally with a minimum amount of effort.” A New York critic wrote, “There is something so different and so wonderfully snappy about the marches of Lithgow. Once you have a Lithgow march you won’t rest till you have them all.”

Lithgow’s skill at orchestration was a key element to the success of his marches, wrote the Australasian Band & Orchestra News. “His writing of the many separate parts necessary for the instruments of a large military band displayed an extraordinary grip of technique, supported by an originality of conception little short of genius.”

Alex Lithgow’s ‘Sons of New Zealand’ performed by the Västmanland brass band, Sweden.

Newcomb wrote that Lithgow was “not only known for his outstanding ability as a composer, conductor and cornet virtuoso, but also for his character, charm, and great modesty.” His grand-daughter and biographer Pat Ward said, “It is curious that such rousing martial music should be the forte of this quiet and gentle man.”

He was proudest of his post-war music, especially ‘At the Movies’, a suite for silent film orchestras.

‘March of the Anzacs’ from 1916. The sheet music cover depicted “the landing of troops and supplies at Kabateple [Gallipoli]” – an early portrayal of New Zealand soldiers at the front. - National Library of New Zealand.

While the relaxed life in Launceston had its attractions for bringing up the three children Lithgow had with his wife Bessie, it also limited what he could achieve in his musical career, compared with living in more cosmopolitan cities. By day, he worked as a compositor, and his after-hours musical life was intense. Besides leading the Launceston St Joseph’s Band for many years, he composed and conducted music for silent films, and founded the Launceston Concert Orchestra to perform symphonic jazz and his own pieces in the mid-1920s.

Lithgow died in Launceston of a cerebral haemorrhage on 12 July 1929. At his funeral, several massed bands played the ‘Invercargill March’. When he died the piece’s popularity was already widespread, and it would increase as the century progressed.

Forty years after Lithgow left New Zealand, in 1934, the Woolston Brass Band recorded ‘Invercargill March’ while visiting Australia, and for two decades it was a best seller. During the Second World War, it lifted the spirits of Australian prisoners-of-war at Changi, Singapore, and it was one of several Lithgow pieces performed at a victory march in Tokyo in 1946. Invercargill acknowledged Lithgow’s success publicising the city by unveiling a stature of him in 2019.

Among many military bandsmen around the world, the ‘Invercargill March’ is affectionately nicknamed ‘In for a Gargle’.

--

First published in Good-bye Maoriland: the Songs and Sounds of New Zealand’s Great War, by Chris Bourke (AUP, 2017).

--

YouTube link:

Footage of the unveiling of a statue of Alex F Lithgow in Invercargill, 2019.

Audio link:

The New York Military Band’s 1913 recording can be heard online courtesy of the Donald C. Davidson Library at UCLA, Santa Barbara.

Links:

Download a piano version of the ‘Invercargill March’ at the National Library website.

Download a piano and band version of ‘Kia Ora: Maori March’ at the National Library website.

Download a piano solo version of the ‘Land of the Moa March’ at the National Library website.

Listen to a 1933 recording of the Woolston Brass Band performing the ‘Invercargill March’.

Stuff: Statue of Alex Lithgow unveiled in Invercargill, 14 April 2019

Sources:

Pat Ward, Alex F. Lithgow 1870-1929: March Music King, P. Ward, Armadale, 1990.

S P Newcomb, ‘The Man who composed the “Invercargill March” – Alex F. Lithgow’, The Mouthpiece, November 1957.

Amanda Mills, ‘“This beautiful song should be in all homes”: First World War sheet music at Hocken Collections’, Crescendo 93, Aug/Sept 2013.

‘Sousa Played His Marches’, Australian Band & Orchestral News, 26 July 1929.

J F Firth and Margaret Glover, ‘Lithgow, Alexander Frame (1870-1929)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, volume 10, 1986.