Former Cleves/Bitch bass guitarist Rob Aickin was always the band member with the tape recorder capturing rehearsals, but he had no production experience when he called on Eldred Stebbing in early 1977.

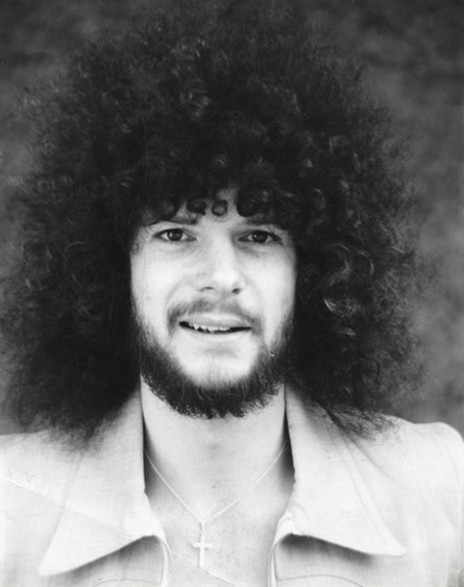

Rob Aickin, early 1970s. - Rob Aickin collection

Stebbing saw something in him and hired Aickin as Stebbing Recording Studios’ in-house producer. A year later he had produced four gold-selling records for Toni Williams, Hello Sailor and Golden Harvest, and been named the nation’s producer of the year at the New Zealand music awards.

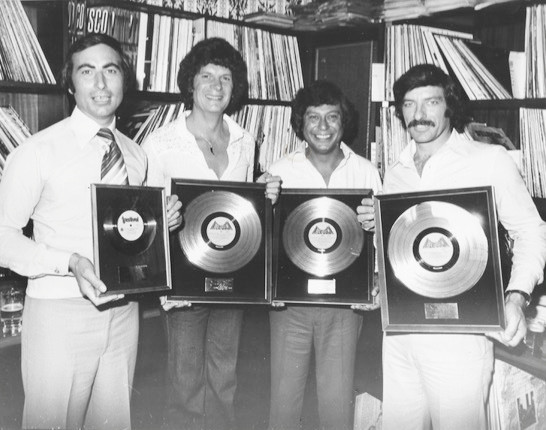

Rob Aickin's gold records and awards. - Rob Aickin collection

When Aickin joined Stebbing’s, they ran a 3M 16-track tape recorder, but a state-of-the-art computerised Quad 8 control panel and a 24-track recorder were installed in mid-1980 in time for Th’ Dudes’ second album Where Are The Boys? (1980) and two platinum-selling Patsy Riggir LPs, Lay Down Beside Me (1981) and Are You Lonely (1982). By the middle of 1981, Aickin had quit the music industry altogether.

Make it more commercial

The first assignment Stebbing gave Aickin was to make ex-Underdogs and Cruise Lane singer Murray Grindlay’s newly finished album more radio friendly. The sessions had been produced by Grindlay and engineered by Phil Yule. Stebbing played Aickin some tracks and Aickin boasted he could make it sound more commercial.

Aickin: “I told him [Stebbing] what I’d been doing and he said, ‘Oh, we’ve just done an album with Murray Grindlay. Why don’t you have a go at remixing,’ or something like that. So that’s exactly what I did, much to Murray’s disgust, I think, because it wasn’t just … There was ego involved in it as well, you know, Murray being a producer himself, I suppose, and musician. I went in and tampered with his little baby, if you like.

“I didn’t even put any overdubbing on Murray’s, I just had to work with what had been recorded; all effects basically and just the mixing. He’s a very fussy and meticulous sort of a character and if it’s not done his way, you know … But I used to get on real well with him. You know, he respected me anyway, in the end. Initially he wasn’t too sure, but there you go.”

Get an album together

Aickin produced Rarotonga-born singer Toni Williams’ 1977 single ‘The One I Sing My Love Songs To’, the follow-up to ‘Rose (Can I Share A Bed With You)’, produced and written by Peter Posa. Both singles brought Williams gold records.

Festival Records MD Ray Porter, Rob Aickin, Toni Williams and Festival A&R man Kevin Williams. - Rob Aickin collection

Aickin: “After the success of the single [‘The One I Sing My Love Songs To’], it was like, ‘Shit, we’ve got to get an album together,’ so we just went straight in and did the album. Just used the same band, it was just a process after that. Ripped through that in no time.

“There was a list of songs. I was sort of given the songs and [told], ‘Deal with them.’ So I did. I put the orders together on the album, but didn’t really get too deep into the picking of the songs. That was more up to Toni and [Festival managing director] Ray Porter, I think, who were coming up with tracks. Because they had a huge library of songs to pick from, from unreleased or obscure albums, and that was where all the material was coming from.”

Plume of beer foam

Immediately on commencing work in the Jervois Road studio, Aickin utilised the session musicians Murray Grindlay had assembled over the previous years to record his jingles. A sort of New Zealand Wrecking Crew, they worked fast and they were highly skilled but they also enjoyed a drink or two.

Aickin: “Session keyboard muso Peter Woods has arrived at the studio for a session, and is sitting at the Stebbings’ pride and joy, the grand piano, which is heavily mic’d up with the finest of microphones. Red McKelvie offers him a can of beer, which he gladly accepts, but what he didn’t know was Red had shaken the shit out of the can just before handing it to him.

“I can still see this plume of beer foam squirting like a geyser across the studio and the look of horror on Peter’s face as he tried to stop it. Eldred would have had a heart attack had he seen it. We sort of tried to clean it up, but everything stunk of stale beer for a couple of days after that. There was a lot of alcohol and smoke around the studio in those days.”

Save me

Not long after the Williams success, former Happen Inn regular Yolande Gibson was looking to relaunch her career after three years in Christchurch and a Vera Lynn tribute LP. An HMV artist of the late 1960s, Gibson was brought to Stebbing’s by Festival and chose to record ‘Save Me’, which had also been the closing track on Williams’ The One I Sing My Love Songs To.

Aickin: “I got in trouble over that one. A couple of the tracks that she recorded were the same songs that Toni Williams had recorded, so I conveniently thought we might as well just use the backing tracks, we’re gonna use the same musicians. Rather than replay it, I thought I’d just use those backing tracks, and she took offence to that and took Eldred to court over it. But they settled out of court.

“So I didn’t like her much for that because I was being economical. It seemed ludicrous to get the same guys in to play the same song to do a thing that had already been done, the same key and everything. Take Toni’s voice off and put hers on, but it didn’t go down too well. She wasn’t really a country singer; she was a bit more operatic, if you like, than Patsy [Riggir] was.”

A very cocky sort of bunch

Hello Sailor had one Radio New Zealand-recorded single under their belt when they strode into Stebbing Recording Studios to record demos in 1977. During studio downtime, Rob Aickin and engineer Ian Morris would polish their sound and help create a New Zealand institution.

Rob Aickin and Hello Sailor with gold records at Stebbing Recording Studio. Hello Sailor manager David Gapes is at left; Festival Records managing director Ray Porter is at right. - Rob Aickin collection

Aickin: “Someone said there’s a really good band playing at The Gluepot. We went up and had a look and it was Hello Sailor of course. Went up and had a chat with them after the gig and said, ‘Come and do some demos down at Stebbing’s.’ They agreed to do that and the rest is history.

“Got them in the studio, which was no mean feat. They were a hard bunch of guys to pull together all at the same time. Dave McArtney had a flat, like, two doors away from the studio at that point, so they’d all go and hang out there and get up to all sorts of mischief. But then I’d get them all together in the studio and let it rip. It was good.

“We did a demo at first and I think when we put it down there were a few arrangement issues so we changed the arrangement of the thing a bit because it went on somewhat. I managed to talk them into changing it around, anyway, and making it more commercial.

“But they didn’t really have too much say in it, you know. Ian and me just went ahead and did what we wanted to do and the guys really didn’t have much to say about it apart from, ‘Shit, that sounds really good,’ you know. So everyone went along with it, but no one could really argue with it.

“Hello Sailor was a classic example of egos. They were a very cocky sort of bunch of guys, especially Graham [Brazier] and Dave. Harry [Lyon] was more mellow, he was the anchor, if you like. The other two guys were off on another planet. There was a lot of ego involved there. They were very hard to pull together. The secret with those guys was when you pulled it together, they were magic, you know, and they just fired.”

Studio trickery

Before returning to New Zealand at the end of 1976, Aickin had spent time in some of London’s best recording studios as bass player in Bitch and Raw Glory, working with producers such as Jimmy Ryan (Carly Simon, Loudon Wainwright III), Tony Ashton (Ashton, Gardner & Dyke, McGuinness Flint), Chris Kimsey (Peter Frampton, Ten Years After) and Muff Winwood (Sutherland Brothers, Mott The Hoople). He picked up plenty of tricks he pulled out during his time at Stebbing’s.

Bitch in the UK around 1971: Ace Follington, Ron Brown, Rob Aickin with Gaye Brown in the front.

Aickin: “Vocals were just standard reverb in a lot of the cases, I think. Actually a lot of the reverb we did was delayed reverb, so, you know, you’d say something and instead of reverb straightaway it would be delayed. So it sort of gave it that bizarre echoey sound. It was quite common in those days. David Bowie used to do it, and that’s where the ideas came.

“We used to listen to a lot of what was going on with the other big artists and pinch their ideas. ‘Oh, that sounds good. Let’s try that.’ And bits of tricks and things picked up overseas with multitracking. It was like the classic George Harrison sound where you’d multitrack your guitar, so when you double track it you detune it. The second track is out of tune and it gives it that big, fat George Harrison-type sound.

“I learnt a lot of that from [Bitch producer] Jimmy Ryan, because he was a brilliant guitar player. He played on a lot of the Bitch stuff on the recordings. There’s a track on the Bitch album called ‘Horizon’, and if you listen to the guitar work on that, it’s bloody brilliant – him and Ron [Brown] playing together. He’s an absolutely amazing guitar player, Jim Ryan. He used to jam with us in rehearsals. When he started playing everything just went up another notch. Best player I’ve ever played with. He was just astounding.

“They were some of the tricks I learned overseas, you know, get the thing to cut through the little transistor. That’s where you want it to jump out because you don’t normally listen to that stuff on a big stereo system at home until you’ve already purchased it from what you’ve heard on the radio. That was the secret. So in spite of the huge, big studio speakers, that was just a bonus listening through them. Most of the stuff was done through little, wee speakers, listening to it, and get a good sound on that, the rest of it was automatic after that.”

Gotta get a good song

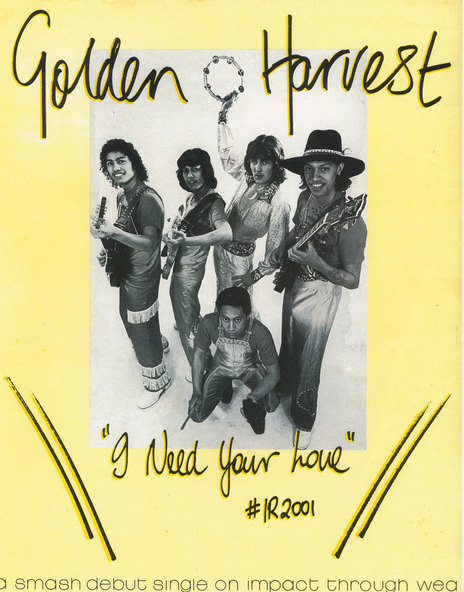

Golden Harvest were long on enthusiasm and short on experience when they showed up at Stebbing’s with the catchy ‘I Need Your Love’. The song would bring the band and Aickin a gold single.

Aickin: “That was actually Benny Levin’s band. Not too sure what deal they had together, whether Benny was paying studio time. But it was sort of fairly limited and restricted, I think. You know, again, we ripped the crap out of them. You know, we got [John Hanlon producer] Mike Harvey in to play that lead keyboard thing. They weren’t really crash-hot, they were a pretty loose band, if you like, but they had a couple of good songs. That’s really all it takes; gotta get a good song and then take it from there.”

A bunch of young kids

Eventually engineer Ian Morris asked Aickin if his band Th’ Dudes could record some demos during studio downtime. The band’s success with single ‘Be Mine Tonight’ and album Right First Time (both 1979) would ultimately bring an end to Morris’s time at Stebbing’s.

Aickin: “They were a bunch of young kids. Dave [Dobbyn] was a way better singer than Peter [Urlich], you know, and I used to scratch my head. But what they were trying to do was, like, a punky/new wave thing was out at the time, you know, sort of like The Clash and all that. The vocal that Peter would do was sort of more in favour with the times, if you like.”

A shitload of records

Rob Aickin’s biggest success in terms of sales was country singer Patsy Riggir. She had been dropped by EMI in 1980, but Eldred Stebbing signed her up and licensed her output to CBS label Epic. Her Aickin-produced records Lay Down Beside Me (1981) and Are You Lonely (1982) were both platinum sellers, helped no end by her national television exposure on That’s Country.

Patsy Riggir with engineer Tony Moan (left) and producer Rob Aickin at Stebbing Recording Studios in the early 1980s.

Aickin: “She probably sold more records than all the others put together. I’ve got two platinums out of her, two platinum albums, and I’m sure she got double, triple platinums out of those. She sold a shitload of records. Ian was gone at that time too. Tony Moan was the house engineer then, so he engineered all that stuff.

“She was very easy to record, whereas a lot of other ones were really difficult to record, if you like. A lot of them, you had to cut in bits and pieces and, you know, just wasn’t quite right. So a lot of them were take after take after take, and then cut this bit in here and that bit there and mix it all together. But Patsy wasn’t like that so much. She was very easy.”

Turn on your lipstick power

When Th’ Dudes came to a halt in 1980, guitarist and songwriter and occasional lead vocalist Dave Dobbyn took the opportunity to record his new songs at Stebbing’s with Aickin and Ian Morris. A single, ‘Lipstick Power’, was unsuccessful but all concerned were excited at what lay ahead. That is, until Dobbyn was locked out when he wouldn’t sign a contract with Stebbing.

Aickin: “It never got the airplay, because no one knew much who Dave Dobbyn was in those days, you know, apart from Th’ Dudes. He was trying to launch a solo career. Again, the promotional machine wasn’t there.

“We used drum loops and everything for drums; we never had a drummer. So just go bash a snare drum and then put it on a loop. Dave played most of the stuff on that and Ian played some of the stuff on it. Dave was a good pianist too. He could pretty much pick up anything and play it. He was good. Clever guy.”

No one’s gonna survive on that

After the failure of the Dobbyn project, Rob Aickin quit Stebbing Recording Studios. Stebbing had consistently rebuffed him when he had asked for a percentage of royalties on the records he had produced. With a second child on the way, he needed to earn some real money and was soon employed as factory manager at a polystyrene packaging manufacturer.

Aickin: “I engineered a lot of Murray Grindlay’s [jingles] stuff too, which was pretty bizarre, because I’d be sitting there operating the desk and everything and Murray’s telling me what to do and I’m sitting there thinking, ‘Yeah, fine.’ Just do as I’m told, sort of thing.

“And that’s what was sort of happening in the end. Everyone else was … Ian had gone, and they were short-handed a lot of the time in the studio with engineers. I even did a demo with Sharon O’Neill. You know, she was a good singer. She was really good. Jacqui Fitzgerald was just as good, she just didn’t get there, if you like, for whatever reason. She was a good singer. Josie Rika was another one too, but Murray used to use them a lot. I used them too on backing up because there was no one else. They were really good backing singers, those girls.

“And New Zealand being such a small audience, on the scale of things, a gold record in those days was only 7500, I think. You know, no one’s gonna survive on that. That was the other problem really. A gold record was fine, but monetary-wise, not gonna happen.

“But just recently married, a kid on the way, I should have really packed up and moved to Australia at that point in time, but I didn’t. I got a job first then started a business. I made more money doing that, so there you go. A lot of regrets about it, but, you know, I did what had to be done at that point in time in order to survive I guess, especially with a young family on the way.”

The dynamic duo

Rob Aickin had struck an instant rapport with Stebbing Recording Studios’ young engineer Ian Morris. Having proved themselves with the success of Hello Sailor, they were given carte blanche to do as they wished, so long as it didn’t interfere with Murray Grindlay’s lucrative jingles income.

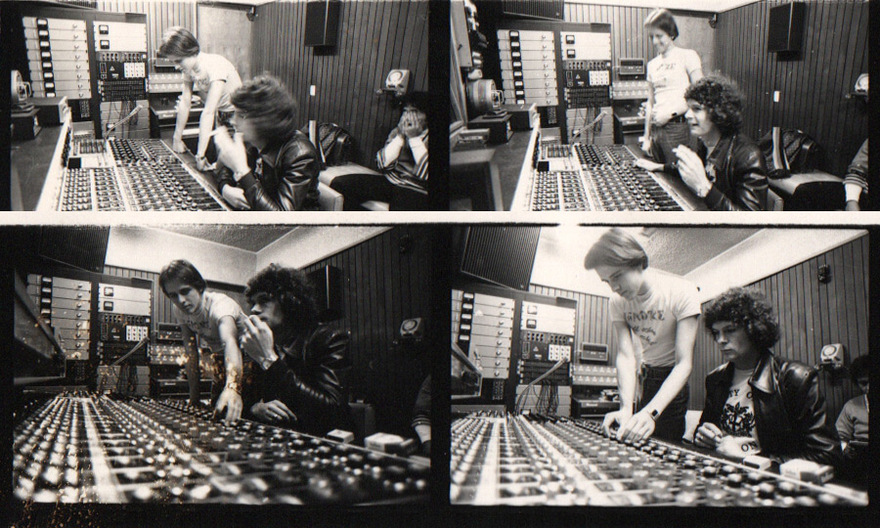

Ian Morris and Rob Aickin recording the debut Hello Sailor album at Stebbing Studios, 6 June, 1977 - Simon Grigg collection

Aickin: “He [Morris] was sort of looking over [former Stebbing engineer] Phil Yule’s shoulder, I think. Because in England when they recorded, all the engineers would have a tape operator, and I would imagine at that point in time Ian was probably looking over Phil’s shoulder and being his tape operator, where he learned his way round the studio.

“But we just sort of clicked straight away. I mean, when I first walked in, he was sort of like, ‘Who the fuck are you,’ sort of thing. But it didn’t take long before he realised what was going on and all of a sudden he thought, ‘Oh, I can see what’s going on here.’ And he jumped on board straightaway and all of a sudden we clicked and everything we did, you know, we both saw the end goal, I guess, and went for it.

“We lost contact when I moved to Australia. I was so busy with my business, trying to get back on my feet again, and had to put my heart and soul into my business and I lost touch with all the New Zealanders and everything.

“Eventually Ian and me stumbled across each other again. He was trying to track me down and he was constantly spelling my name wrong. That’s why he couldn’t track me down. We started to communicate on a regular basis again. So even in the later years we stayed in touch and got in regular contact.

“I was absolutely dumbfounded when he took his life. I was shocked, because my daughter took her life, and when he found out he was absolutely floored. And when he did the same thing I was just gobsmacked. I couldn’t believe it.”

--