Playing in soul and R&B-based bands in New Zealand and Australia, Tony Backhouse knew something of the history and singing traditions behind the music.

But it was a particular recording that opened his ears and drew him closer to the music’s roots: ‘You Don’t Know What the Lord Has Done for Me’, an old gospel song, sung by Annie Lee and Oscar Crawford with Annie Mae Jones, recorded in the early 1970s by musicologist David Evans for an album entitled Sorrow Come Pass Me Around: A Survey Of Rural Black Religious Music.

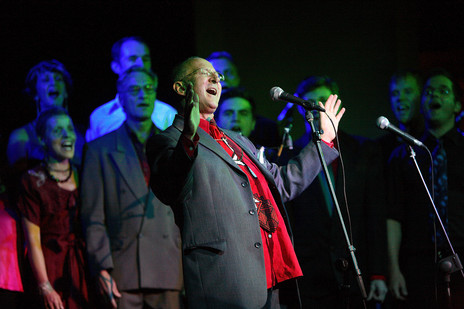

Tony Backhouse, Café of the Gate of Salvation, 20th anniversary, 2006.

“They are not gospel performers”, he explains. “Their names don’t appear anywhere except on this one CD. They are just church folk from Mississippi, sitting on a porch singing this song, a very simple song. And they don’t sing, from an aesthetic point of view, particularly well, but they sing it with such commitment and investment in it that there’s something else. It sounds kind of exotic, beautiful in its own kind of way. It’s like coming through the jungle and finding this really weird and rare kind of flower. It might even be poisonous; it looks so good. And I thought, there’s something here I’ve got to find more out about and put into the sort of music that I do.”

In Sydney, where he was living at the time, there were a couple of local radio shows specialising in American roots music. “I got in touch with these deejays and asked where I could find more of this stuff, because there was nothing in record shops except Mahalia Jackson’s Greatest Hits which wasn’t quite what I wanted. I wanted more of this raw, congregational, semi-improvised harmony sound.”

They directed him to records of Sam Cooke and the Soul Stirrers, The Pilgrim Travellers, Spirit of Memphis Quartet: gospel groups who had consolidated the “quartet” vocal style (though there were often more than four in the groups) in the 1950s.

Determined to find where this music might exist today, he began writing to people currently involved in the gospel scene in the United States, from black performers to white scholars. The Reverend Al Green never replied, but he received warm and helpful responses from Tennessee-based scholars David Evans, Doug Seroff and Lynn Abbott, all of whom were engaged in collecting histories of gospel quartets in the southern United States.

Tony Backhouse and Jann Hing with Rev Malcolm Collins, New Orleans 2018.

Tony began making frequent trips to the US, eventually basing himself for six months in Memphis, Tennessee. He met men who had become his idols, such as R H Harris, founder of the Soul Stirrers and mentor to Sam Cooke, and Claude Jeter, the former coal miner who had founded the sublime Swan Silvertones. “I was determined to seek them out, even if they weren’t still singing, just to pay my respects. And luckily, I got to just about meet everybody, from Jeter and Harris to the Caravans – the great female gospel quartet from the 60s – as I happened to be in Chicago when there was a Caravans reunion.”

Backhouse’s experience in the black churches has been one of “acceptance and humility”

Seroff introduced Tony to existing quartets in Birmingham, Alabama, and he went in search of gospel choirs in Harlem, New York. “We found the best-dressed man on the street in Harlem and asked him ‘Where do you worship?’ And he said, ‘Round the corner at the Baptist House of Prayer. It was a poor church, a small choir, it wasn’t like they were fantastic singers, but it had an infectious spirit and commitment and energy that sucked me in.”

Returning to Sydney, he imparted his own passion for this music, and some of the techniques he had acquired, to The Café Of The Gate Of Salvation, the choir he had formed in 1986. The joy was infectious. Tony was soon in demand as a host of workshops in Australia and New Zealand, in which roomfuls of gospel neophytes would, within a matter of hours, find themselves harmonising, soloing and singing call-and-response in an approximation of an African-American church choir. From these workshops, further choirs would spring, including New Zealand groups Jubilation, Heaven Bent, and Gale Force, though not all focused exclusively on the African-American tradition. Tony began taking groups from down under on “gospel tours” of the United States, visiting churches in New Orleans, Birmingham and New York, where he and his compatriots would often find themselves joining in with the black singers and were sometimes asked to solo or sing something of their own.

While some members of the COTGOS had travelled to the States with Tony on his gospel tours, the choir made its first visit as a performing group in April 1999, guesting in churches from New Orleans to New York.

Inevitably, groups of mostly white, middle-class Antipodeans singing in a tradition rooted in the historic struggles of African-Americans raises issues of authenticity and appropriation. Are choirs like COTGOS – which are not just predominantly white but also largely atheist – really able to channel the same spirit as a black choir in a southern Baptist church? Are they connecting with the oppression of African-Americans, or simply ripping them off?

In 1996, after hearing a recording of The Café Of The Gate Of Salvation, African-American academic and singer Patrick Johnson began a study of white Australian gospel choirs. Though it might sound like an ironic reversal of Tony’s quest, his object was to examine the politics of appropriation. In his essay Performing Blackness Down Under: The Café of the Gate of Salvation Johnson concluded that “their catharsis is brought on not by the universality of gospel ‘touching’ them in the same way it does African-Americans, but rather by the shedding of residual traces of British propriety … It is as if they are discovering for the first time a hidden part of themselves. What they are ‘connecting with’ … is not the oppression of African-Americans but rather a part of themselves that has been underdeveloped or lying dormant.”

Tony Backhouse, singing in an Australian gorge, 2010.

Though Johnson describes how, at the first Café rehearsal he attended, he was impressed by the power and convincingly ‘black’ sound of the choir, he still felt something was missing, until he witnessed them, in 1999, singing as guests in a black storefront church in Harlem. After performing a couple of songs to mild appreciation, one choir member had stepped forward to tell tearfully of her brother’s death the day before the choir left Sydney, prompting calls of ‘Have mercy!’ and ‘Bless the Lord!’ from the congregation. The Café then launched into a performance of the Clark Sisters’ ‘You Brought The Sunshine’ and, as Johnson notes, ‘something broke’; the church pianist joined in and ‘there was an uproar as the congregants rose to their feet and began to sing along.’ In this moment, he suggests, “performer, Subject and audience” all “traverse[ed] the world of the Other”.

The white gospel choir’s “performance of their own and the Other’s identity”, he concludes, “is never a static process. Rather, it is always in flux and flow, a performance of possibilities.”

As for Tony, his experience in the black churches has been one of acceptance and humility.

“Their response to anyone who comes in is ‘Whosoever comes in, let them come’. They are incredibly generous and welcoming, especially if you are from halfway around the world.”

Tony Backhouse in Heavenly Light Quartet, Sydney 2019.

What he has learned from the gospel churches, he says, “is actually about being more fearless. Because being in a black church and singing in front of a black congregation is challenging, but because it’s also going to be the best audience you’re ever going to get it’s also encouraging, and you feel like you’ve got permission to do whatever you want.

“There’s nothing like being in front of a black church audience and just singing something that sets them off because you just get it back, big time.”

Cultural appropriation? As he told Kim Hill in 2018: “They see what I do as a tribute to their tradition … not as their tradition being plundered. They want this music to belong to the world.

“The only people who come out waving that particular flag tend to be white liberals. All the African-Americans I hang out with love the fact that I’m singing their kind of material. And I do it with as much love and respect as I possibly can.”

--

https://www.australianmusiccentre.com.au/article/on-the-road-with-tony-backhouse