Written for Mushroom magazine, 1981.

The most intriguing thing about Dunedin’s second-hand record shop is that it doesn’t have a name. No name at all. You might think it has one, but try looking it up in the phone book. Mind you, there have been a few quarter-hearted attempts at getting one.

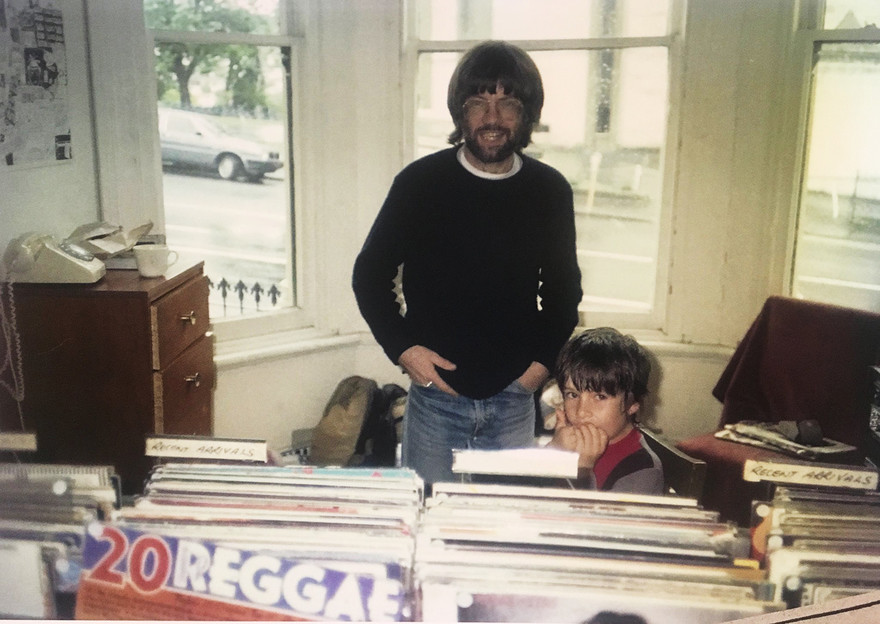

Roy Colbert inside Records Records with son Jesse, 1984. Photo by Pat O'Neill.

Record bags have been at the root of the matter. The shop started around 1970 and progressed happily through to about 1975 using record bags belonging to other shops and various record companies and so on. Caused a bit of havoc at the bank with cheques and stuff, but the more liberal tellers soon learnt to totally disregard whom cheques cashed at the shop were actually made to. Then around 1975 the bags ran out. Panic.

UEB Industries didn’t appear to have any overt connections with South Africa, so we decided to accept their tender for the bag-producing, even though they hadn’t actually lodged a tender for the job at that actual point in time. We felt they would eventually, once the word got around the industry, so we gave them the contract out of respect for that future decision. What’s the name of your shop, asks the UEB man, business-like. Our shop has no name we reply somewhat proudly. But UEB certainly weren’t about to do business with people with no name so sort of instantly I said “Astral Weeks Records”. I thought that would look as good as anything on the bags and besides, I happen to think that particular record is a nugget.

Astral Weeks Records, soon to be renamed Records Records. - Murray Cammick Collection

So for a couple of years it was “Astral Weeks Records”. Not in the phone book and not in the ads either, coz there hardly ever were any ads (picture the demoralisation when a customer hands a fistful of albums over the counter and asks “how long have you guys been going” – thinking three days because he’s always prided himself at being up with the play – and you reply “eight years”).

Inevitably the “Astral Weeks” record bags ran out and it was back to UEB. Same man, a little greyer and slower with pen but still business-like. What was the name of the shop again, he asks. Our shop has no name came the reply, firm and filled with stubbornness, we wish the bags to be brown with nothing on them. We cannot charge a shop with no name he replies wearily. We will pay cash comes the reply, triumphant.

So the problem appeared to be solved. But then, Fresh Developments. The Upper Stuart Street terraced houses were bought – bought and redecorated. Suddenly there are more shops and the talk went to signs and names. Three names loomed as the most worthy candidates to be painted on the wall adjoining the front door: “Acme Records”, “Records Records” and the sublime “Records Records Records”.

The feeling on the Board regarding “Acme Records” was that it was a little subtle for all those Joe 90s who walk the pavements of Dunedin, dollars in hand, waiting for their eyes to be caught by catchy signs. The people who matter we said, imperiously and with a certain degree of verve, were already coming to the shop. But the Joe 90s must be attracted if the shop is to progress came the reply. So, reluctantly, the tribute to the once-astoundingly fine television flick Roadrunner (where everything was “Acme”) was shelved.

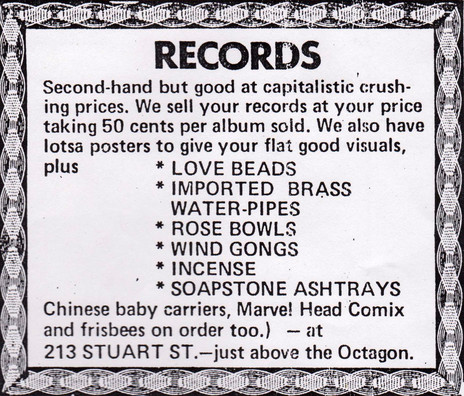

Advertisement for a shop with no name, Crux magazine, 1971. - Burny Brosnan

The choice now lay between “Records Records” and “Records Records Records”. It was a tough one. The former lacked the latter’s marketable overkill, the latter seemed a trifle gross: the former didn’t seem to reveal enough, the latter could even be seen as wordy. The debates raged but in the end modesty and underkill prevailed. We are not selling used cars or fire-damaged women’s clothes we resolved, we will lay back.

“Records Records” was also a cheaper by one-third to have painted on the wall.

But it still didn’t go into the phone book, the question of shop name was dexterously avoided in the ads, and we still asked all the customers to write “cash” on the cheques.

When the shop began it introduced the rather unique concept of commission selling (unique for second-hand shops that is). We will take 50 cents, you price the record yourselves we proclaimed boldly. If the record deserves to sell at the price you put on it, it will sell, and you will be paid. It did occur to us also at this time that all shops should be run on this principle … this obviated a whole number of irksome things. Principally it meant a vast stock was quickly acquired without shelling out vast capital (we didn’t have vast capital) but just as enjoyably it took away the haggling that is part and parcel of second-hand shops everywhere.

(And also, I think people who run a shop work on the premise that the customers are assuming you’re ripping them off blindly.) But so what, they want the goods and you’ve got them for sale, so can I have this this please? But with the customers doing the record-pricing, it was kind of hard to say we were ripping anyone off.

There was a drawback or two doing it this way. The paper work drove you right up the goddamn wall. And you had to sell a mountainous number of albums at 50 cents a time to have what us in the second-hand trade refer to, crypto-semantically, as a “good week”. But simultaneously I was being employed by a number of newspapers and periodicals around the country and being grossly over-paid by them, so it wasn’t desperately important to sell as many records as EMI or Pink Floyd each week to eat a square meal.

But gradually the drawbacks of the 50 cents commission system started to gnaw irreparably deep at the Board, and the command went out to introduce actual “buying and selling”. The 50 cents thing was retained of course as an option (record prices, incidentally, had more than doubled since the shop’s inception) but as at September 1981, it forms only about one-third of the intake.

when the shop began it was closed for 20 minutes each afternoon for a snack or whatever. More often than not, a whatever.

The hours also lengthened as the shop moved into the 1980s. Previously it had been midday till 5, and then open again for two more hours Friday nights. In fact no, I lie, when the shop began it was closed for 20 minutes mid-afternoon for a snack or whatever. More often than not, a whatever. But now it opens at 11am – and doesn’t close for a two-hour tea break Friday nights. No Saturdays. Still hardly what the Taiwanese work (they having recently fought bitterly and successfully to have their 65-hour week reduced to 60) but record people don’t really hit the streets early morning. Unless someone somewhere is having a sale, and even then many of them don’t take it.

The final development of note for the shop was a move through the wall (well, down the hall and back into a room which was actually, as the borer flew, through the wall) at the same time as the outsides were done up. At least a lease, and the Board celebrated by throwing out the cardboard cartons, getting real record bins, putting in some warm carpet, painting the old cash register originally housed at the now-no-more Otago Boys High School tuck shop at the top of Cargill Street (it fell off the back of a truck – the cash register, not the tuck shop), sticking some nice things on the wall, painting the wall… and most importantly, remembering to move through the wall first.

There are now plenty of second-hand record shops around New Zealand, from Invercargill to Auckland. They’re fun to run and while retail records continue to rise at dangerous speed they’re obviously worth doing. Record companies assume punters get to know a record the moment it hits the stores so if sales are bleak after nine months – bang! They delete, and suddenly records which people are only then discovering, are no longer available. The second-hand and record dealer thrives on such impatient industry folly. Gram Parsons’ flawless Grievous Angel is one of a thousand examples of records that just weren’t given a chance. Sure, many of the hard-to-gets are subsequently re-released, but in the interim the second-hand price climbs. And of course some, like J D Blackfoot’s curiously revered Song of Crazy Horse, don’t (can’t) come out again.

$20 and $30 albums aren’t found at the Dunedin shop and probably because commission customers aren’t allowed to put $30 on an album, we miss out on a percentage of the genuinely rare stuff. But it does seem that some of the prices being asked for various records around the country are palpably absurd, even if the defence – people are paying the prices asked – is unanswerable.

America started all of this of course. American record collectors are legendary for their fanaticism. One of them spent an Easter with us and unfolded stories that would make even your most resilient albums curl at the edges in astonishment. An old surfing album by The Fantastic Baggys (songwriters Phil Sloan and Steve Barri) which he spied in my collection, occasioned a tale of a collector in San Diego who paid $400 for it. Only he didn’t have the money right at that minute, so he drove home, got the money and drove straight back. A round trip of just under 500 miles. (The album, incidentally, is quite average.)

The premise that if someone will pay $30 for something then that shall become that record’s price is a dubious one indeed.

The friend also told tales of California’s “swap meets” (Joey Ramone refers to one on the excellent ‘7-11’ track on the latest Ramones album). These began rather like the parking building car boot sales in Auckland’s K Road a few years ago – people would turn up with their boot full of old records, pay a nominal fee for a space at a giant parking lot, and the collectors and vinyl junkies would swoop. That was three years ago, and then they were starting at 9am. Now the thirst is so intense that the starting time has been pushed further and further back to the current kick-off time of 1am in the morning – collectors darting from one car to the next, flashlight in hand.

Record auctions have also helped establish the high-priced second-hand record. The premise here, that if someone will pay $30 for something then that shall become that record’s price is a dubious one indeed, but again the evidence tends to make it a hard one to argue against.

Records are bought in at Dunedin’s shop at around two-thirds what they’re put out for. If you know the records you’re dealing with, that’s a marginal but safe enough percentage, but it must be realised that there is nothing more useless than an unwanted record – mint condition notwithstanding. An unwanted tape you can use again, but an unwanted record you cannot sell at any price. Retail shop managers are a lot more painfully aware of that than I or any other second-hand dealer will ever be.

Silvios in Wellington have bins where you can buy 13 albums for $10. We actually have them at 15 for $10 (yes, Silvios’ albums are much better than ours – it’s a great shop), but both our throwaway bins move slowly. Personally I would have thought 15 albums for less than the price of one was a bargain no one could pass up, but that just underlines the disinterest people have in those unwanted records.

At the Dunedin shop we sell all kinds of music after dealing principally in rock for the first few years. Being upstairs cuts our potential easy-listening clientele to shreds (housewives with large prams consequently buy their James Last albums at EMI for $10.50, not realising that we give housewives with prams three James Last albums for free, just for walking through the door) and rock has remained our most saleable item. Classical buyers are rarer in numbers and a lot more fussy as regards record condition (understandable enough) and straight supermarket top twenty pop, perhaps contrary to expectation, is most difficult to shift. Only 78s sit longer, in fact 78s take so long to sell we don’t sell them at all.

45s are better – Echo Records in Christchurch bear testimony to the market there. All the good ones from the magical 60s era are eagerly sought after – often as 45s too, not as tracks on an album. 45s are now seen strictly by the industry as ads for albums, so one can see 45s getting even more collectable still.

So, what else? I could write about the crazy customers, the genuinely certifiable space cases that only record shops seem to dig out, but that would take a thousand pages. At least. I could ruefully recall the time the feminist broadsheet (Broadsheet) cited one of our Critic ads as sexist (it was a reference to a record recalling “a memorable woman” or something – an ahead of its-time plea for tolerance towards lesbians that was grossly misinterpreted) or I could maybe list which famous rock stars have bought at the shop on wet nothing-to-do pre-concert afternoons. Or, or, or, or, …

For a small shop with a pretty small clientele a lot seems to happen. It must be unbelievable working in Woolworths.

--

This article first appeared in Mushroom: a magazine for alternative living in New Zealand (issue 26, October 26, 1981), as “Dunedin’s Second-hand Record Shop”. It is republished here with permission.