Mahina Tocker – musician, singer, songwriter, lesbian mother – is of Ngāti Raukawa and Tainui descent. Most of her music is directly about her being a Māori woman, and her songs are also gifts to her young daughter Hinewairangi, telling her of her language and her heritage. Mahina explains how the album came about.

“Lesley Smith from Emmatruck Music wanted a woman’s record made and she asked me to do it. She’s an engineer who is learning the ropes and she’s working with Paul Streekstra. I really admire what she’s doing, and the energy that’s there from the other women is so supportive.

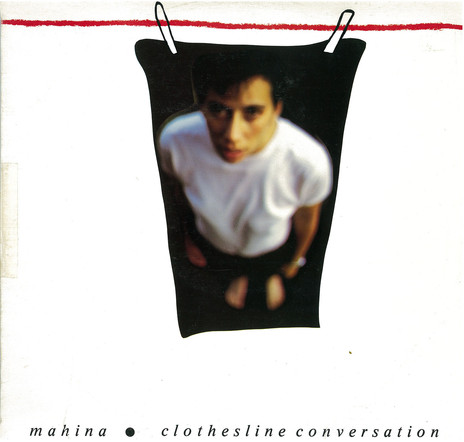

Cover of Mahinaarangi Tocker's 'Clothesline Conversation' album (Emmatruck, 1985).

“We’re having to fork out of our own pockets for bills so it’s a bit of a struggle. I can’t see that we’re going to make a large profit, but if it means the record is going to get out and women are going to hear it and learn something from it and maybe think, ‘Oh fuck, I can do that too,’ then that’s really neat.”

Mahina goes on to talk about her background. “I identify as Māori but there’s also the Jewish aspect. The song ‘No Lines On My Face’ on the album – that’s to do with my father’s heritage [Jewish] and to do with my struggle as a Māori woman. Like identifying myself as Māori but knowing that my father, who I’m really close to, has another heritage. He speaks Māori fluently and he and my mother are really strong with Māoritanga. He never denied being Jewish, but he also went through a lot of pain because of it and he was on his own without a Jewish group around for support. ‘No Lines On My Face’ is a sort of anti-war song, but it’s also a whole mixture of things – self love … identity …

“I went to Israel and went through a whole thing of sorting out who I am. ‘No Lines’ is the only song I think I’ve written that’s to do with me being Semitic. I’m not actually Jewish because my mother’s not Jewish, but the Semitic ties I have are Jewish ties.”

We talked about the new album and how she wrote quite a lot of the songs a long time ago and some were brand new. I asked about the song that gave the album its name, ‘Clothesline Conversation’.

“I wrote that in 1979 when I was still identifying myself to myself as a lesbian. I hadn’t got into the whole domestic heterosexual scene. I don’t know why I wrote it. It probably came from just watching people, and I think I was looking at myself as standing up for myself – a strong woman – but I didn’t recognise the song’s significance then. I lived it afterwards and then it made sense. Lots of stuff that I wrote years ago when I was really young – a teenager – I’m still writing music to now, because I can understand it. It’s much stronger than it would have been when I was 15 or 16 because I didn’t know exactly what it meant then.”

‘Clothesline Conversation’, according to Mahina, is one of the strongest songs on the album. It’s an amazing piece, full of compound timing and a mixture of jazz, rock and roll and classical sound and influences. Each instrument symbolises for Mahina a different aspect of a woman’s story: the steady bass line is her constant existence, her heartbeat; the changeable guitar rhythm is the frustration and confusion felt by her male counterpart and reflecting the woman’s own feelings; the lyrics are her thoughts, bringing the slow realisation that freedom is possible; and the clarinet is the woman’s soaring spirit, tentative at first, then finally breaking free. Mahina says, “It’s all about her taking her dignity back.”

The story is part of Mahina’s own life. The original poem was written for four years before she realised that she had subsequently lived her own words. The music has been written in the last year.

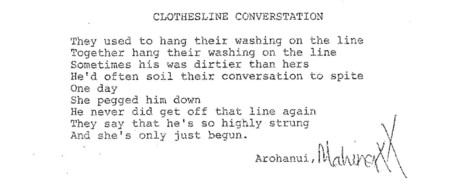

Original lyrics/poem included with Mahinaarangi Tocker's 1985 album 'Clothesline Conversation'.

Each instrument in the song works in a different rhythm to all the others, and prior to going into the studio to record the song Mahina had heard the full piece only in her head.

“It was really scary going into the studio. It was all there in my head, but I thought ‘God! Everyone will panic because they’re going to hear all the different rhythms and they’re not going to click until it’s finished. It was so exciting getting to the point where it clicked. Paul and Lesley were just amazing. They just showed so much respect. I’d told them the song was going to be hard to understand at first and I asked them to accept that and just be patient and wait and they did that. I’ve not had to stop and explain any of the music. They have never said to me, ‘This feels wrong’. They’ve just accepted that I know what I’m doing and that’s also been the case with the other performers on the album. They know that I know what I’m doing and that what’s in my head will make sense when they hear the result. And I feel really good about it all too, because when I’ve heard it through my ears, it has made sense!”

Mahina is on guitar, percussion, lead vocals and harmonies on the album. The other performers are Clare Bear on bass, Nicky May on clarinet and saxophone, and Kimai Tocker and Mahara Valkman – Mahina’s sisters – on vocal harmonies. There is also one song which is not Mahina’s. ‘Young Māori Woman’ is written and performed by Hinepounamu, and Mahina and Mahara perform backing vocals.

“I’m not into standing up and making big speeches, but I say how I’m feeling about an issue or in my life in songs. Takes away a hell of a lot of explanation and verbalising the emotions! The music itself often provides the emotions even if you don’t fully understand what the words are about. All of my songs are love songs in one way or another. A protest song is still a love song to me. To say that something makes me feel sick or that I hate something means I must love something else. To be anti-war means I love life. Long ago I knew there was something for me that was really relevant.

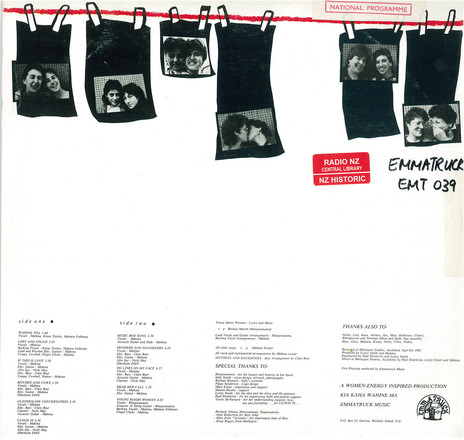

Back cover of Mahinaarangi Tocker's 'Clothesline Conversation' album, recorded at Harlequin, Auckland, 1985.

“It’s only now I can say that my vessel for communication is music. I find it really hard when people ask what a song means, because it’s so individual. People can take from a song what suits them. It’s important that they keep what makes sense to them – rather than me tell them what it means - because I’m not like everybody else. They have to hear it themselves and feel what they feel.

“‘Lost and Found’ – which has a reggae/ska feel – is about my respect to my ancestors, my respect to my mother. There are lots of songs I don’t know why I wrote [them]. They just happened, like I was meant to write them but I don’t know why. It’s like somebody else wrote them and they just came through me. It’s probably because I live my being as a Māori woman and it’s difficult to explain what that means. Maybe that’s what is happening with these songs. ‘Wahine Toa’ I wrote for Kimai and Mahara and me. It’s our song. It talks about calling myself black, which isn’t a colour thing, it’s a strength thing. The song says, ‘My mother is strong, my sisters are proud’. My mother and my sisters are really strong women. And I know who I am. I don’t have to explain to other people about my being Māori. Other people are responsible for their own ignorance!”

--

Jess Hawk Oakenstar is a widely traveled solo guitarist/singer/songwriter and “one-woman band” who was born and raised in Zimbabwe. During her 10 years in New Zealand, she was part of the Web Women's Collective that released the compilation album Out of the Corners in 1982. This album featured recordings by women such as The Topp Twins, Mahinaarangi Tocker, Diane Cadwallader, Hilary King, Val Murphy, and Hattie St John. Currently living in Arizona, Jess performs solo and with a duo, Wayward Maggie.

--

© Jess Hawk Oakenstar – published with her permission. First published in Broadsheet, November 1985.