Born in Auckland on 18 July 1959, Don remembers his grandfather singing him songs from the Boer War, and with both Scottish and Irish blood it’s perhaps not surprising that many years later his voice often carried a classic Celtic yearning on the wings of its melodies.

Don’s parents were both teachers, and although neither of them was a serious musician, both were musical and loved music, and they encouraged him to try different instruments. He started learning cello and piano from the age of seven, with many other instruments added to his musical artillery during his teenage years. Attending Westlake Boys’ High School on Auckland’s North Shore, he played keyboards in local bands but things ratcheted up a few notches while studying at University of Auckland, where he put his abilities on the French horn and percussion to good use in the Symphonia of Auckland (later called the Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra, or APO).

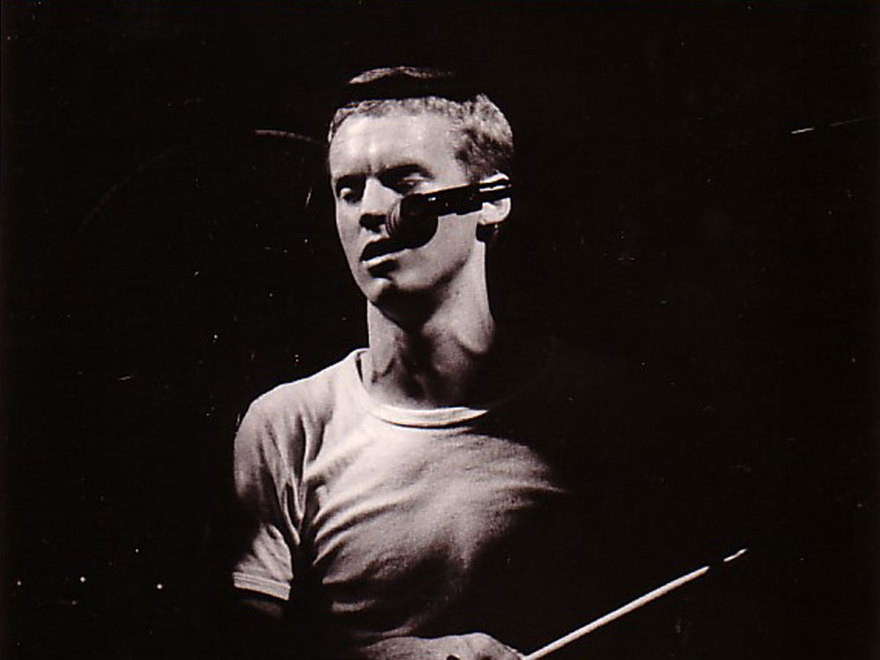

Don McGlashan, 1981.

“I thought I was going to be a classical French horn player from the age of 15,” says McGlashan. “I started with percussion so I could play percussion in orchestras as well. So for a while I was holding down a job as a second horn in the Auckland Symphonia and playing percussion sometimes, and really loving it, soaking up all this wonderful music … and then From Scratch turned up.”

In Phil Dadson’s unique ensemble From Scratch, the participants learnt to bang on and blow an inventive array of made-up percussion instruments, including tuned PVC piping. It was as visually arresting as it was sonically entrancing. Admired internationally in experimental music circles, From Scratch was a project that Don returned to between other projects over the years, and the experience shaped him.

“I was really interested in a kind of compositional, mathematical, philosophical, political way, and From Scratch was a juncture of all these ideas, and opened me up to the visual arts world because we’d go to these festivals and we’d be in panels with all these painters and looking at their practice and what they were trying to do. I’ve not got much of a visual sense but could appreciate all the things that you have in common when you’re painting, trying to grab the world and filter it through your craft and put it on a canvas.

Don McGlashan in From Scratch.

“There’s so much to learn about making stuff and putting it in front of people, and all the disciplines have got so much to talk to each other about. So that was a wonderful gift, and also to just be around people like Phil Dadson … just breathing in the world and it comes out as art, but it takes enormous discipline and waking up early and staying focused, and the lifelong dedication of it gave me a template.”

McGlashan performed on and off with From Scratch from 1979 through the end of the following decade, and he is on every one of the aggregation’s highly prized recordings from that era. But of course, he was an equal part of a highly democratised vision, and these weren’t songs.

While the discipline and vision of Dadson was enormously important to McGlashan, he always felt a little like an observer. Besides, “I just wanted to play all the instruments I could and learn everything under the sun, and play in all these different groups and collaborate. Some people have a burning passion to put their ideas out in front of people and be the centre of something, have a band around them, but I think that happened to me quite a bit later.”

Rock music was never specifically on McGlashan’s agenda, but he was open to anything, so when asked to play occasional onstage horns for theatrical, punk-influenced group The Plague, he would run between gigs, sometimes appearing still dressed in his orchestral tuxedo. This group of punk-influenced politicos – led by writer-poet Richard von Sturmer – wasn’t built to last. A riot of art-punk contradictions, when von Sturmer exited stage left, the group was rechristened The Whizz Kids. Consisting of vocalist Andrew Snoid/McLennan (later of Pop Mechanix), Tim Mahon (bass), Mark Bell (guitar) and drummer Ian Gilroy (later of The Crocodiles and The Swingers), the group hired McGlashan to play rhythm guitar and saxophone. Shortly afterwards, it combusted when both Snoid and Gilroy opted out. And when that happened, Don became the group’s singing drummer.

Don McGlashan - Jenny Pullar

“I was in From Scratch at the time,” he says. “We went to the South Pacific Arts Festival in Papua New Guinea in July 1980, along with Limbs, the Waihirere kapa haka party and some poets. When Andrew and Ian left, Tim, Mark and I decided to carry on as a band. Richard suggested the name Blam Blam Blam, and I locked myself away in Frank Stark and Mary-Louise Brown's warehouse gallery on Federal Street for a few weeks, and learnt how to play kit by listening to The Specials, Booker T and The MGs and Clash records.”

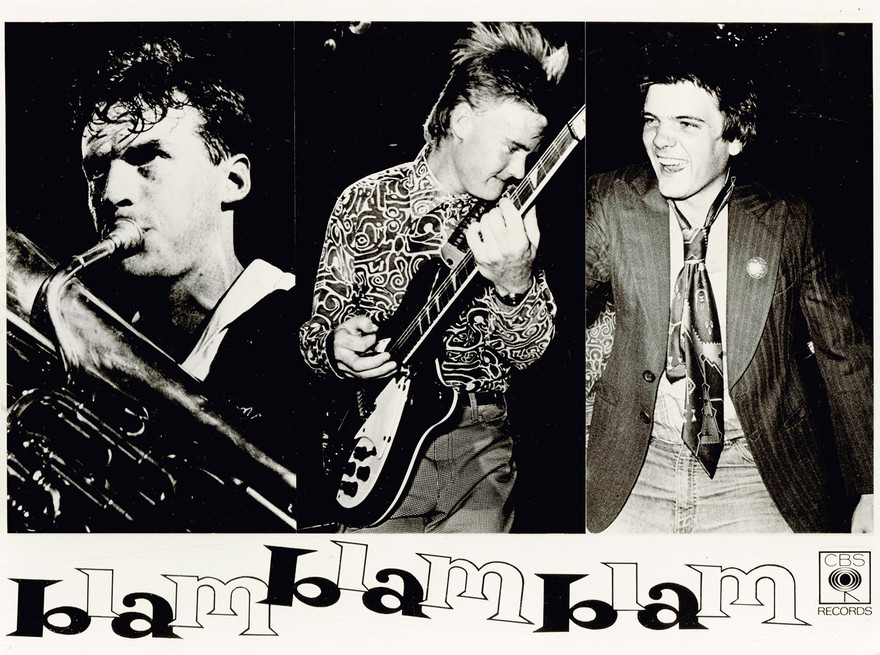

Blam Blam Blam would instantly become New Zealand’s quintessential art-pop band

Blam Blam Blam would instantly become New Zealand’s quintessential art-pop band with their blend of acute, political and cultural references and a smart mix of contemporary musical influences, and the group’s music remains as fresh and vital today as it ever was. In fact, if McGlashan had disappeared off the map after the group’s short lifespan was over, he’d still have attained a very special place in New Zealand’s music culture, despite the fact that he wrote very few of the group’s songs.

Although von Sturmer physically left The Plague before its evolution into The Whizz Kids and then Blam Blam Blam, his lyrics provided the group with some of its most memorable moments.

McGlashan’s contention, however, that he contributed minimally to Blam Blam Blam’s songs is disingenuous. While the lyrics of perhaps their most well-known song, ‘There Is No Depression In New Zealand’, are von Sturmer’s, McGlashan wrote the music. Mark Bell’s politically oriented writing capture the mood of the times and give the group much of its flavour, but the few songs that McGlashan wrote alone are something else: cryptic, mysterious, otherworldly, and absolute classics.

“I’d just started writing stuff,” he says. “Initially, most of the Blam Blam Blam songs were us realising lyrics by Richard. That was a way that we could get lots of music out there and learn how to be a band, and it was kind of like a nursery forest, we could grow up through it. And I’d written a few things: ‘Marsha’ and ‘Call For Help’ and a few other songs.”

Blam Blam Blam: Don McGlashan, Mark Bell, Tim Mahon.

Few songwriters, first flexing their nascent writing muscles, have started out better than McGlashan. The first real hint of his writing talent was ‘Respect’, a cut on the 12-inch Blam Blam Blam EP released in May 1981. McGlashan has claimed that it’s an experiment in the hip-hop style. Whatever inspired it, ‘Respect’ – with anti-authoritarian lyrics that cleave close to the social commentary template of the band, is an astounding piece – with its ticking drum machine, echoed military drums, distinctive bassline, parping euphonium and declamatory vocals. It’s an experiment, but one that works.

‘Don’t Fight It Marsha, It’s Bigger Than Both Of Us’ is an alternative anthem, an instant classic that never gets old, with a lyric that is supposedly about political power struggles, and ambiguous enough to also sound like a creepy, post-relationship lament. It’s undoubtedly one of our greatest songs, and it consistently gets voted as such. Then there’s ‘Call For Help’, a spooky piece of genius with the addition of Ivan Zagni’s astringent 11-string guitar. Amazingly, all the signature characteristics of McGlashan’s songwriting are in ‘Call For Help’: the slightly doleful melodies, and words that are at once descriptive and deeply mysterious. This song, all by itself, is a master class in songwriting, and yet it’s right at the beginning of his writing career.

The Blams came along at a politically tumultuous period in New Zealand, with families and friendships wrenched apart by opposing views on the contentious 1981 Springbok rugby tour, and the group was emblematic of the times, as well as being at the head of a genuine renaissance of New Zealand pop. The group – signed to Simon Grigg and Paul Rose’s legendary Propeller label – managed only one EP, two singles and an album, Luxury Length, before passing into history prematurely when a vehicle accident at the end of a tour promoting their album in May 1982 resulted in Tim Mahon losing most of a couple of fingers.

Given his background, it was never certain that McGlashan would form, or get involved in, another rock band. And for quite a while, he didn’t. Soon after the demise of Blam Blam Blam, he was off to live in New York for a year to play drums for Laura Dean’s dance company, and it was another radical change of direction.

“I was in the orbit of people who’d worked in the Steve Reich ensemble, so there was a lot of that really interesting minimalist stuff, which was great because it really chimed in with what I’d been doing with From Scratch,” he says. “We did a lot of touring but I’d always come back to New York. There were six dancers and two musicians. And so it was like this whole grocery bag of possibilities at the time. I went hungrily after all that and listened to as much music as I could. I was flatting with one of Steve Reich’s pianists. She played on a piece of music I wrote and it was all a great learning experience. I was going out and listening to Richard Hell and the Voidoids and the Golden Palominos. Laura Dean took me in hand and got me tickets to everything, including the whole eight hours – stretched over two nights – of Laurie Anderson’s United States Of America show.

In New York, McGlashan was “bombarding” himself with musical possibilities

“I was bombarding myself with all these different possibilities. I didn’t really want to start a band and thought that maybe I could come back to New Zealand and do solo stuff involving spoken word and technology.”

And then, a revelation. “I was seeing a lovely woman who was also part of the Steve Reich orbit, a vocalist who sang on records like Tehillim and Music For 18 Musicians, and she had this wonderful collection of Irish folk music. So I’d be out there listening to all this crazy stuff, but then I’d go back to her place and listen to these songs of yearning and loss, very simple chord structures, beautifully made, mostly really old songs, mostly anonymous, old songs passed down. And I guess that went in most deeply.”

However it took a while to find the right vehicle in his own music for his newfound interest. Back in New Zealand, he re-joined From Scratch, and lent a hand to various projects. Late in 1982 he had collaborated with experimental guitarist Ivan Zagni on a 12-inch EP, ironically named Standards, and it’s a good example of a project that doesn’t quite come off. Mostly instrumental, ‘This Is A Love Song’ bears enough McGlashan character to warrant attention, but mostly it’s pleasant tinkering that may have ended up in something more coherent had there been an album-length budget.

There would be numerous other ways to keep busy, including his first foray into film soundtrack work and, in 1985, an anti-South African rugby tour single, ‘Don’t Go’, recorded as Right Left And Centre, with an all-star cast including Chris Knox and Rick Bryant. In the same year, McGlashan really found his feet again when he teamed up with actor Harry Sinclair in the audacious musical-theatrical show, The Front Lawn.

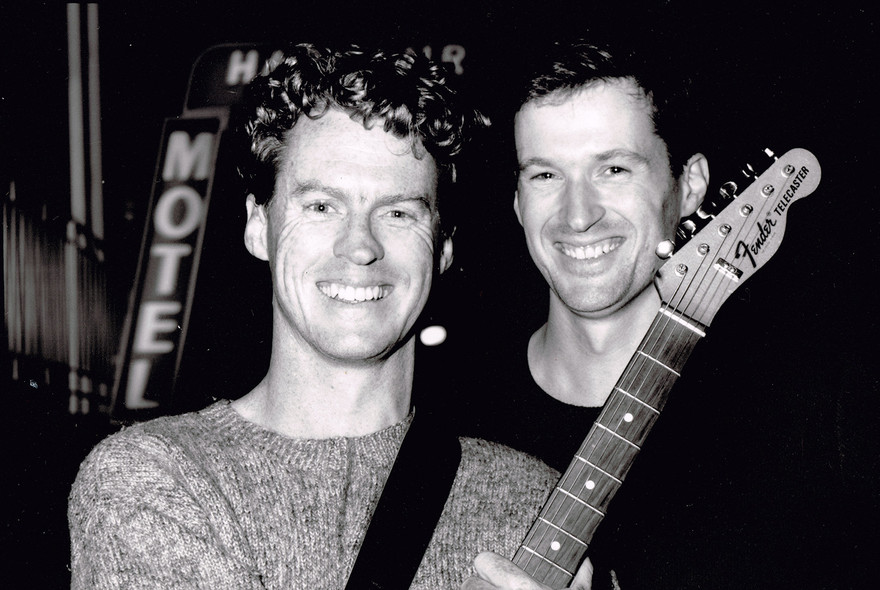

Don McGlashan and Harry Sinclair, The Front Lawn.

While Blam Blam Blam had satirised conservative Kiwi mores and modes, The Front Lawn went the whole hog in a part-acted, part-sung presentation that took the piss out of our safe suburban lifestyles and our way of life in general, but in a generous way that wasn’t just poking the borax at an oppositional “them”, but also gave permission to laugh at ourselves. The Front Lawn was unparalleled, and it’s impossible now to convey just how revolutionary it was at the time, with creative set design (including the duo’s travelling grass-covered sedan), comic turns and great songs. There was ample room for the show to fall flat on its face, and this tension raised the ante, as it does with all good comedy and social commentary.

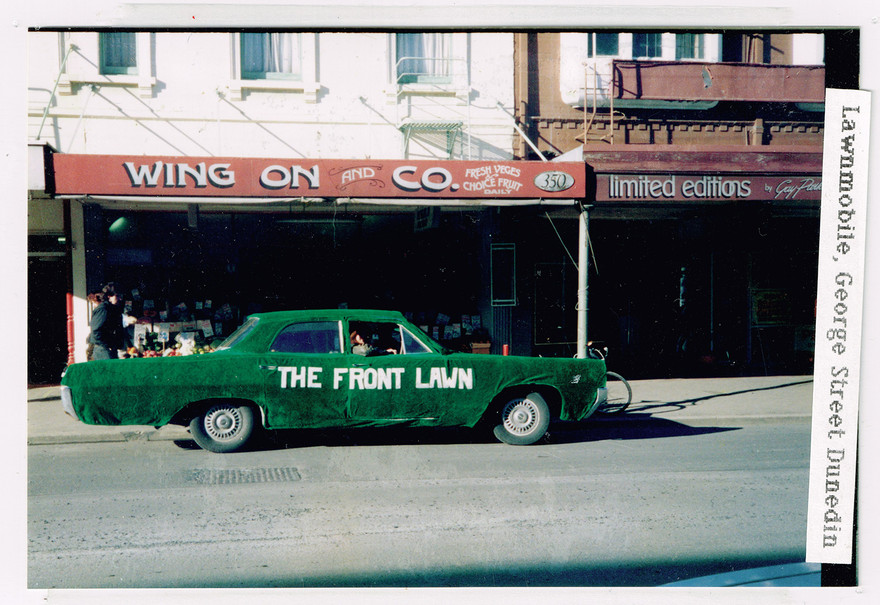

The "Lawnmobile" - Don McGlashan collection

Precisely at the time New Zealand needed it most, The Front Lawn was colloquial, with a surreal absurdity but also genuine emotional resonance. The Front Lawn was also explicit notification of McGlashan’s wicked sense of humour, although there was room in the show for show-stopping seriousness, too. Set pieces with lawnmowers and washing machines were a heck of a lot of fun, and contrasted beautifully with the occasional completely sober ballad. ‘Andy’, a song McGlashan wrote – with help from Sinclair – about his late brother, is the perfect example. With tear-inducing lyrics, it sounds like a cover of an age-old Irish folk song, constructed with a precision that is totally in aid of the gravity of the sentiment. One of the greatest songs from a catalogue of great songs, the potency of ‘Andy’ has never diminished.

“When we started The Front Lawn, the songs I was writing during the process, I was learning about storytelling,” says McGlashan. “There were quite a lot of directions we went in at once – some things which are quite surreal and language based and some ideas which were essentially films, which we did onstage, and then later on we’d make them into films. But the musical side was quite often musical storytelling, which had roots back into the Celtic stuff I’d been opened up to in New York – like ‘Andy’ and ‘Claude Rains’. Quite simple things, which were just a way of telling a story.”

At the beginning, Don’s collaboration with Harry was simply a convenient way for two young men just back from their OE to flex their creative muscles, but it soon grew legs, then wings. “Harry didn’t want to go back into ordinary theatre as an actor and I didn’t want to go back into ordinary bands, and it was a case of us trying to work out what we thought had strength, what could we make that was lasting and what could we do that was using our skills and everything about ourselves but not much else, not much in the way of production … we didn’t need a big PA or lights or smoke.”

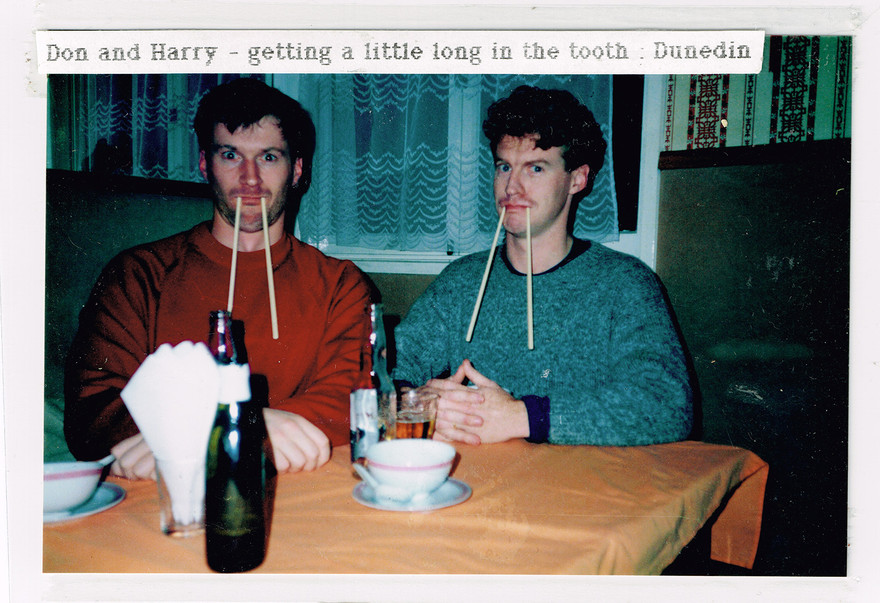

The Front Lawn: Harry Sinclair and Don McGlashan goofing off in Dunedin.

‘How You Doing’ was something like a short film. “I had a piece that I brought to the table which was about madness, because I was dealing with a friend who was really in trouble. And the initial sketch was ‘I’m standing and I’m talking to someone who’s just walked up to me, and I’m reaching into my bag for a response and I keep pulling out the wrong one.’ The idea had a lot of pathos and terror, that the ice that we skate on – which broadcasts our normalness to other people that we meet – is very thin, you could fall through it any minute, and this friend of mine was repeatedly falling through it. And left to my own devices that would have been a really sad song.

“But Harry and I talked about it for a while and then he said, ‘Let’s just workshop it’. And we tried it as just a dialogue and then it turned into a thing called ‘The How You Doing Dance’, which is funny. ‘Where are you living, anyway?’ ‘Well, you’d hardly call it living. I’ve lost my job. Having quite a few emotional problems.’ So we thought, ‘This is interesting, this has gone a completely different direction to what we thought it would do. Does it still carry some of the freight of the original idea?’ And we tried it and just continued working on it until it did. It had dancing in it, and then we ended up putting it on the record and it turned into something else completely with the Six Volts and these wonderful Cairo bazaar-type horns. But that was just emblematic of how we could explore something and learn about it at the same time.”

It’s a great pity that the two extant albums – while they’re entertaining reminders of the some of the songs from those Front Lawn shows – only tell half the story, and sadly, there’s little in the way of filmed evidence of the critically acclaimed shows that they took far and wide internationally. They do, however, have the wonderful short films.

“We both thought it would be really interesting to put our ideas in films, and so we made the short films, and there’s not many of them but they pulled a lot of energy into them. I still have sketch ideas that I put in these books, which I look at and think, ‘That’s essentially a Front Lawn idea’. We’d have all these sketches and bring them along to each other and go, ‘Is that a song? A film? Is it something where we talk to each other and it turns into a song, or we talk to each other and it turns into movement?’

“I DIDN’T WANT TO BE A SWISS ARMY KNIFE, I JUST WANTED TO BE A KNIFE!” – DON MCGLASHAN

“And that was the cool thing, that we didn’t put any restrictions on where an idea could go, and rock and roll compared to that is very restrictive … And so it was wonderful to have the lid lifted off and I think that we’re both better artists having had that. Harry’s done his really cool films and he’s living in Los Angeles now and writing and directing and he’s done wonderful work, and I think I’m a bit more sure of myself in terms of when I sit down to write, because we had that six years of hammering out things like, what it means and why you get up in front of people.

As great as The Front Lawn was, it was never going to be a forever project. By 1989 they had added actress Jennifer Ward-Lealand, but Sinclair and McGlashan were about to focus on their specific talents and areas of interest.

“With a lot of art forms the paraphernalia that sits around it distracts you from the actuality of it … but if you’re starting something that doesn’t have much context like The Front Lawn … there wasn’t anybody around that had managed, promoted, exploited, husbanded, because there hadn’t really been many things like that. We referred to a lot of old forms, like old duo stand-up, but we weren’t really stand-up, we were more surreal than that. And that meant there were no distractions, just two guys sitting in a room trying to write something going, ‘Why are we doing this?’ Always interrogating what we were doing. And in a way that’s what you have to do when you’re doing anything.”

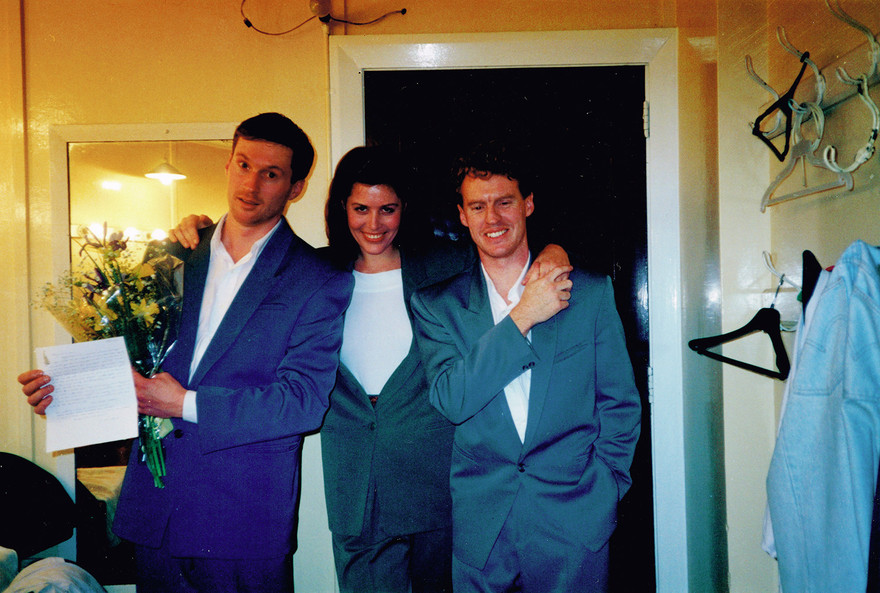

The Front Lawn: Harry Sinclair, Jennifer Ward-Lealand, Don McGlashan.

“We worked together in this amalgam of theatre and film and music and then at a certain point Harry realised that he was a filmmaker. It took me a bit longer to realise that I didn’t want to do these multifarious things – I didn’t want to be a Swiss Army knife, I just wanted to be a knife! And my knife was to write songs and that’s why I started The Mutton Birds. But that was late in the piece. I was already 29, nearly 30. Most people have worked things out a bit earlier than that.”

--

Read Don McGlashan – part 2