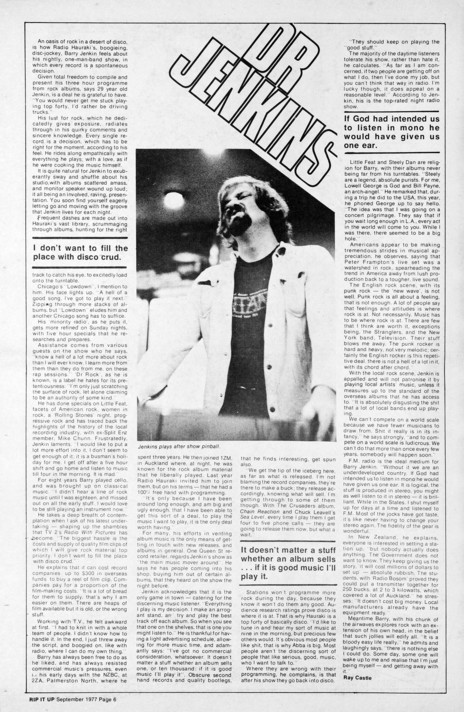

When Rip It Up spoke to Barry Jenkin for its fourth issue, in September 1977, the legendary radio host was about to undergo his punk epiphany.

--

An oasis of rock in a desert of disco, is how Radio Hauraki’s boogieing disc-jockey Barry Jenkin feels about his nightly one-man-band show, in which every record is a spontaneous decision.

Given total freedom to compile and present his three-hour programme from rock albums, says 29-year-old Jenkin, is a deal he is grateful to have. “You would never get me stuck playing Top 40, I’d rather be driving trucks.”

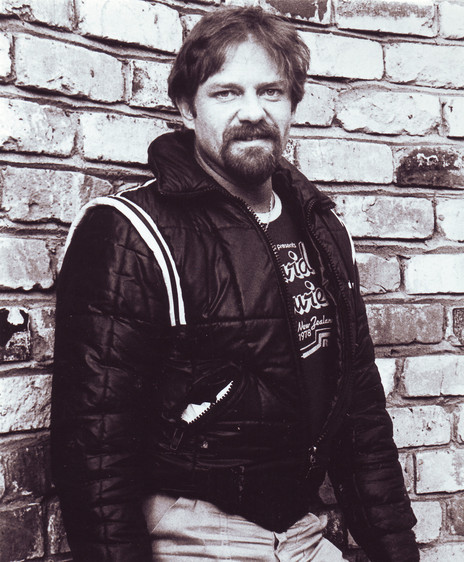

Barry Jenkin in the late 70s.

His lust for rock, which he dedicatedly gives exposure, radiates through in his quirky comments and sincere knowledge. Every single record is a decision which has to be right for the moment, according to his feel. He rides along in empathy with everything he plays; with a love, as if he were cooking the music himself.

It is quite natural for Jenkin to exuberantly sway and shuffle about his studio, with albums scattered amass, and monitor speaker wound up loud, it all being an involved, raving, presentation. You soon find yourself eagerly letting go and moving with the groove that Jenkin lives for each night.

Frequent dashes are made out into Hauraki’s vast library, scrummaging through albums, hunting for the right track to catch his eye, to excitedly load onto the turntable.

Chicago’s ‘Lowdown’, I mention to him. His face lights up. “A hell of a good song, I’ve got to play it next.” Zipping through more stacks of albums, but ‘Lowdown’ eludes him and another Chicago song has to suffice.

His “minority radio”, as he puts it, gets more refined on Sunday nights, with five-hour specials that he researches and prepares.

Assistance comes from various guests on the show who, he says, “know a hell of a lot more about rock than I will ever know. I learn more from them than they do from me, on these rap sessions.”

“Dr Rock” – as he is known – is a label he hates for its pretentiousness: “I’m only scratching the surface of rock, let along claiming to be an authority of some kind.”

He has done specials on Little Feat, facets of American rock, women in rock, a Rolling Stones night, progressive rock, and has traced back the highlights of the history of the local recording industry, with ex-Split Enz member Mike Chunn. Frustratedly, Jenkin laments, “I would like to put a lot more effort into it, I don’t seem to get enough of it; it is a busman’s holiday for me. I get off after a five-hour shift and go home and listen to music till four in the morning. It is mad.”

For eight years Barry played cello, and was brought up on classical music. “I didn’t hear a line of rock music until I was 18, and missed out on all the early stuff. I would love to be still playing an instrument now.”

He takes a deep breath of contemplation when I ask of his latest undertaking – shaping up the shambles that TV2’s Radio With Pictures has come. “The biggest hassle is the cost and supply of quality film clips of which I will give rock material top priority. I don’t want to fill the place with disco crud.”

Working with TV, he felt awkward at first. “I just threw away the script, and boogied on.”

He explains that it can cost record companies up to $300 in overseas funds to buy a reel of film clip. Companies pay for a proportion of the film-making costs. “It is a lot of bread for them to supply, that’s why I am easier on them. There’s heaps of film available but it is old, or the wrong stuff.”

Working with TV, he felt awkward at first. “I had to knit in with a whole team of people. I didn’t know how to handle it. In the end, I just threw away the script, and boogied on – like with radio, where I can do my own thing.”

Barry has always been free to do as he liked, and has always resisted commercial music’s pressures – even in his early days with the NZBC at Wellington, or 2ZA, Palmerston North, where he spent three years. He then joined 1ZM in Auckland, where, at night, he was known for the rock album material that he liberally played. Last year Radio Hauraki invited him to join them, but on his terms – that he had a 100% free hand with programming.

“It’s only because I have been around long enough, and am big and ugly enough, that I have been able to get this sort of a deal, to play the music I want to play, it is the only deal worth having.”

For many, his efforts in venting album music are the only means of getting in touch with new releases, and albums in general. One Queen St retailer regards Jenkin’s show as “the main music-mover around”. He says he has people coming into his shop, buying him out of certain albums that they heard on the show the night before.

Jenkin acknowledges that it is the only game in town catering for the discerning music listener. “Everything I play is my decision. I make an arrogant stand, and try and play the best track off each album. So when you see that one on the shelves, that is one you might listen to.” He is thankful for having a light advertising schedule, allowing for more music time, and adamantly says, “I’ve got no commercial consideration, whatsoever. It doesn’t matter a stuff whether an album sells one, or 10,000: if it is good music, I’ll play it.” Obscure second-hand records and quality bootlegs, that he finds interesting, get spun also.

“We get the tip of the iceberg here, as far as what is released. I’m not blaming the record companies, they’re there to make a buck; they release accordingly, knowing what will sell. I’m getting through to some of them though. With the Crusaders album, Chain Reaction and Chuck Leavell’s Sea Level, every time I play them, I get four to five phone calls – they are going to release them now, but what a wait.”

Stations won’t programme more rock during the day because they know it won’t do them any good. Audience research ratings prove disco is where it is at. That is why Hauraki is a Top 40 of basically disco. “I’d like to tune in and hear my sort of music at nine in the morning, but precious few others would. It’s obvious most people like shit, that is why Abba is big. Most people aren’t the discerning sort of people that like serious, good music, who I want to talk to.”

Where they are wrong with their programming, he complains, is that after his show they go back into disco.

“They should keep on playing the good stuff.”

The majority of the daytime listeners tolerate his show, rather than hate it, he calculates. “As far as I am concerned, if two people are getting off on what I do, then I’ve done my job. But you can’t think that way in radio. I’m lucky though, it does appeal to a reasonable level.” According to Jenkin, his is the top-rated night radio show.

Little Feat and Steely Dan are religion for Barry, with their albums never being far from his turntables. “Steely are a legend, absolute purists. For me, Lowell George is God and Bill Payne, an archangel.” He remarked that, during a trip he did to the US this year, he phoned George up to say hello. “The idea was that I was going on a concert pilgrimage. They say that if you wait long enough in LA, every act in the world will come to you. While I was there, there seemed to be a big hole.”

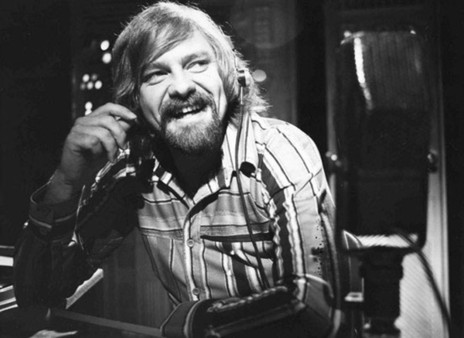

Barry Jenkin, 1978

Americans appear to be making tremendous strides in musical appreciation, he observes, saying that Peter Frampton’s live set was a watershed in rock, spearheading the trend in America away from lush production back to a tougher, live sound.

The English rock scene, with its punk rock – the “new wave”, is not well. “Punk rock is all about a feeling, that is not enough. A lot of people say that feelings and attitudes is where rock is at. Not necessarily. Music has to be where rock is at. There are few that I think are worth it, exceptions being the Stranglers, and the New York band, Television. Their stuff blows me away. The punk rocker is hard and heavy, not very melodic; certainly, the English rocker is this repetitive deal, there is not a hell of a lot in it, with its chord after chord.”

With the local rock scene, Jenkin is appalled and will not patronise it by playing local artists’ music, unless it measures up to the standard of the overseas albums that he has access to. “It is absolutely disgusting the shit that a lot of local bands end up playing.

FM RADIO IS THE IDEAL MEDIUM. “IF GOD HAD INTENDED US TO LISTEN IN MONO HE WOULD HAVE GIVEN US ONE EAR.”

“We can’t compete on a world scale because we have fewer musicians to draw from. Shit it really is in its infancy,” he says strongly, “and to compete on a world scale is ludicrous. We can’t do that more than once every few years, somebody will happen soon.”

In New Zealand, he explains, everyone is interested in setting a station up, “but nobody actually does anything. The Government does not want to know. They keep giving us the story, ‘It will cost millions of dollars to set up’ – absolute rubbish. The students, with Radio Bosom, proved they could put a transmitter together for 250 bucks, at 2-to-3 kilowatts, which covered a lot of Auckland.” He stresses: “It doesn’t cost big money. Local manufacturers already have the equipment ready.”

FM radio is the ideal medium for Barry Jenkin. “Without it we are an underdeveloped country. If God had intended us to listen in mono he would have given us one ear. It is logical, the stuff is produced in stereo, you might as well listen to it in stereo – it is brilliant. While in the States, I shut myself up for days at a time and listened to FM. Most of the jocks have got taste, it’s like never having to change your stereo again. The fidelity of the gear is wonderful.”

Meantime Barry, with his chunk of the airwaves, explores rock with an extension of his own head, in the belief that such jollies will edify all. “It is a bloody easy life really,” he admits, and laughingly says, “there is nothing else I could do. Someday, someone will wake up to me and realise that I’m just being myself – and getting away with it.”

--

This originally appeared in issue four of Rip It Up, September 1977, and is republished with permission. At the time, FM radio was still five years away.

Barry Jenkin in Rip It Up, September 1977.