Every Labour Weekend out Wainuiomata way, 40 minutes from the hustle and bustle of Te Whanganui-a-Tara, among the 260 hectares of native bush and parkland known as the Brookfield Outdoor Education Centre, the Wellington Folk Festival does what it’s been doing since 1965: gathering around the light of folk music, and passing its warmth among the people.

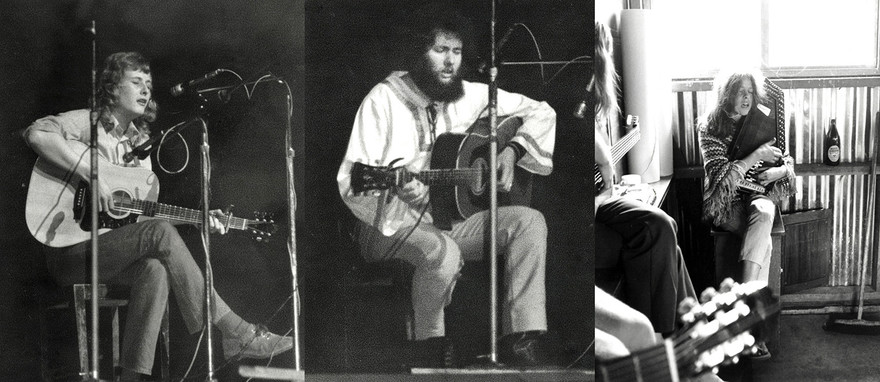

The Warren Brothers at an early festival. - Wellington Folk Festival Collection

The gates to a Wellyfest (as it is fondly known) weekend open at 3pm on the Friday to a Village Green atmosphere, complete with folk-related craft stalls, some of which pop out of the house trucks their proprietors arrived in. There are food and drink vendors on site, children’s entertainment and youth programming, and events – including ceilidhs – running right through until the Sunday night. With a variety of camping options available (the property is owned by Scouts NZ), tickets are available for half-days, days, evenings, or the whole weekend. The 2025 festival is extra special, being the 60th anniversary of the first event. Like many of the most legendary festivals, there may sometimes be mud, but there will always be dancing; the legendary Michael Parmenter MNZM was a dance host in 2023, teaching balfolk (a revival of traditional European folk dances).

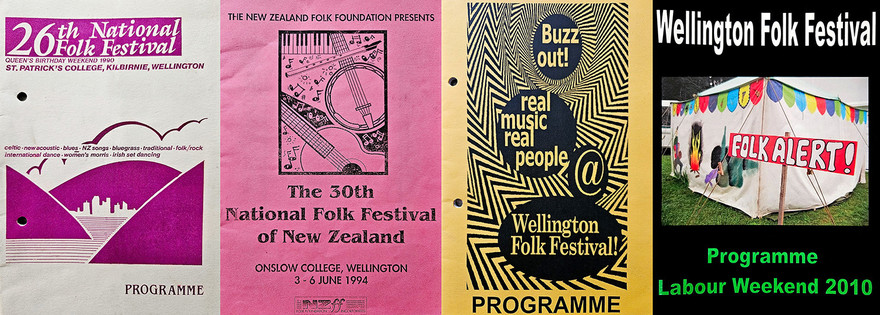

Wellington Folk Festival programmes (L-R): 1990, 1994, 2002, 2010. - Wellington Folk Festival Collection

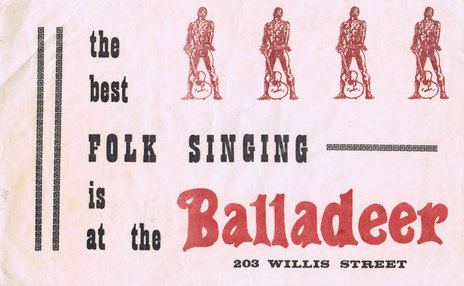

A folk festival has been held in the Wellington Region since 1965, growing from popular sessions at the Monde Marie and The Balladeer Coffee Bar. According to its most comprehensive historically recorded source – Folk in Wellington, penned by country/bluegrass musician and longtime chronicler Sharyn Staley in 2005 – the actual years of anniversaries jumps around a bit (sometimes marked on a fourth year of the decade, and sometimes the fifth). One thing for certain is that, when it began in the 1960s, there was a folk revival happening worldwide, which influenced much enthusiasm for folk music in Wellington.

Promotional poster for the Balladeer. - Robyn Park collection

Major early influences on the Wellington folk scene included Mary Seddon and Max Winnie. The latter was an enthusiast who carried others along with him, introducing new flavours and giving the folk community a much-needed sense of direction and cohesion. Frank and Mary Fyfe arrived in Wellington from Australia in 1965, and took over management of the Balladeer Coffee Bar. It was there, among the make-do furnishings – over coffee, “Jamaica punch”, and toasted sandwiches – that the beginnings of the Wellington Folk Club emerged.

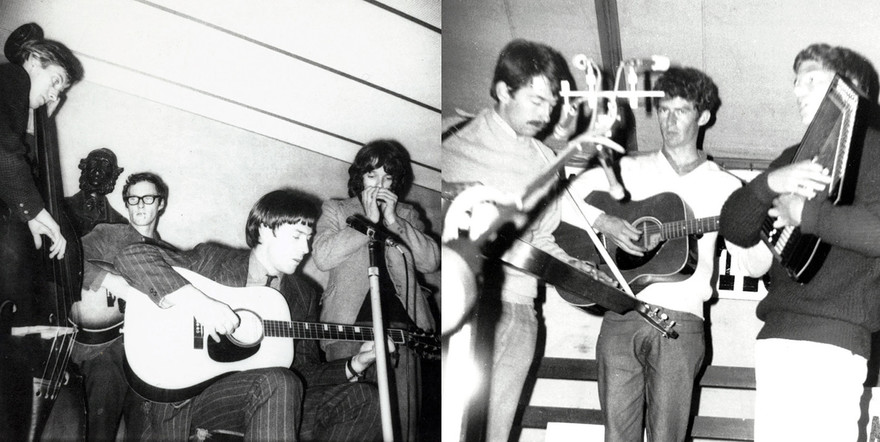

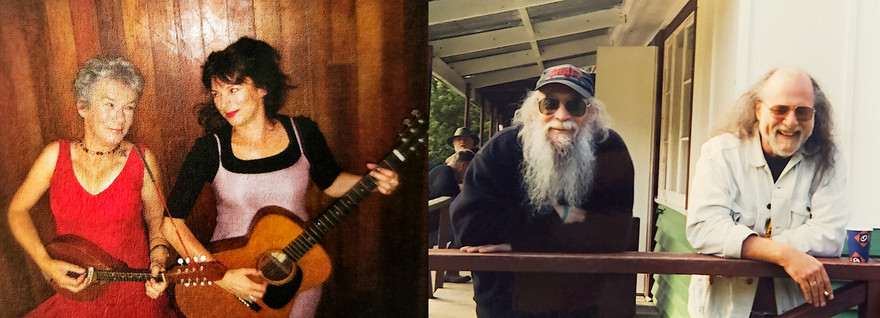

Frank Fyfe and Phil Garland; Frank Sillay and Don Milne. - Wellington Folk Festival Collection

The first wider gathering was a national festival, held over Labour Weekend 1965, at the Blue Triangle YWCA Hall, on Boulcott Street in the city, and in the Victoria University of Wellington (VUW) Memorial Theatre. The brainchild of arts champion Peter Frater (who would later go on to help set up the Newtown Festival, organise the Island Bay Festival, and save the St James Theatre) and Bernie O’Brien, assisted by Winnie and compered by filmmaker and folk fan Hugh Macdonald, it attracted musicians from Christchurch to Auckland. Performers included: Winnie, Val Murphy, Rod MacKinnon, John Sutherland, Warwick Brock, Jae Renaut, Bill Taylor, Frank Scaglione, Hugh Canard, Arthur Toms Trio, John, Geoff & Linda, Debbie Anne, Ron Davis, Bruce King, Hilton Paul, Bruce Holt, Peter Gilmore, Marjie Robson, John Potter, Pauline Harter, and the Wayside Singers.

Ron Craig and Marg Pullar at an early Wellington Folk Festival. - Wellington Folk Festival

The following year it was held on Queen’s Birthday Weekend at the Trades Hall, in Wellington’s Vivian Street. Later in 1966, with backing from a number of folk club members keen on researching New Zealand’s folk music history, Fyfe formed the NZ Folklore Society (NZFLS), with the Wellington branch functioning as the national office. Following shortly after, circa 1967-68, were an Auckland branch (formed by musicologist Angela Annabell) and Christchurch branch (formed by New Zealand folk legend Phil Garland QSM). In his book Faces in the Firelight (Steele Roberts, 2009), Garland said the prime aim of the NZFLS was to create a more widespread awareness of the part our folk culture played in shaping our society. Members collected songs and other folklore materials, promoted folk music, and published the Penny Post newsletter. At the height of the society’s popularity, branches had also sprung up in Taranaki, Manawatū, and Hawke’s Bay. (The NZFLS wound down in the mid 1970s, but the festivals kept the embers glowing.)

Above left: the final concert at the 1966 festival. Left (L-R): Colin Heath, Gordon Collier, Max Winnie, Andrew Delahunty. Right: Graeme Lovejoy, Bruce Gardener, John Butt. - Wellington Folk Festival Collection

The National Folk Foundation was established in 1967, and this group ran the next five festivals. The fourth National Folk Festival (1968) gained sponsorship from Rothmans, as well as Victoria University FMC and the NZ Folklore Society. A new approach was taken, with genre sections being delineated (traditional, blues, contemporary, country, instrumental) and an increasing focus on workshops and talks. Workshop leaders included Winnie, Fyfe, and singer/songwriter, bluegrass and folk musicians such as Frank Scaglione, Dave Jordan, Paul Metsers, Arthur Toms, Peter Trenwith, Gordon Collier, fiddler Colleen Bain, banjo man Don Milne – and the charismatic manager of Auckland’s Poles Apart Folk Club, Curly Del’Monte.

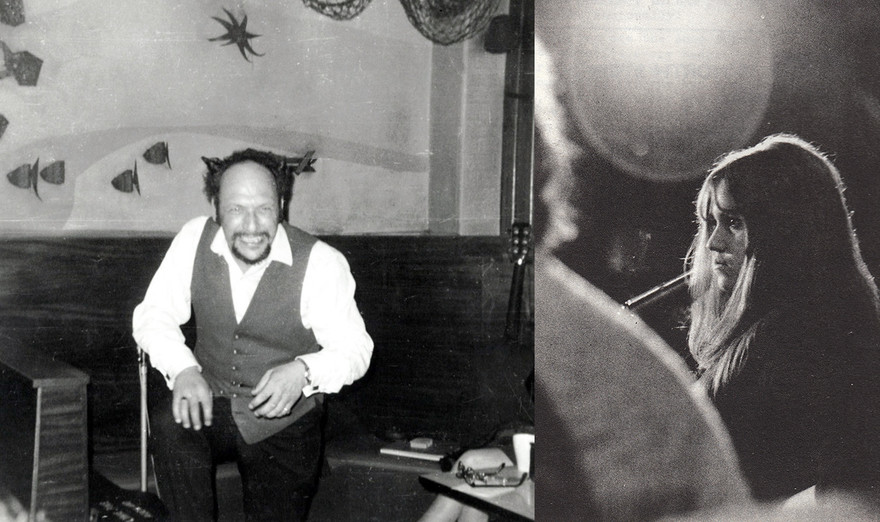

Above: Curley Del’Monte (at Monde Marie café); and Val Murphy, at the 1969 National Folk Festival, Wellington - Wellington Folk Festival Collection; David Colquhoun Collection

Fyfe, who was now chairman of the Folk Foundation, worked very hard with his committee for the 1968 event’s success – also spending the weekend commuting between the festival and Hutt Hospital Maternity Ward, where a daughter was being born. Attendance at the festival’s Final Concert exceeded everyone’s expectations, and the audience overflow was moved into another room. The performers were doubly applauded for the stamina they displayed, having come off one stage in the first hall, then repeating their act for a second audience. Both crowds agreed it was a concert for the ages.

Those early festivals brought mostly (but not exclusively) New Zealand musicians and enthusiasts together for jamming and performances. In 1968 an official programme of workshops was introduced, formalising the “passing on of skills” aspect of each gathering.

The Balladeer, which had played such large part in the Folk Club scene, closed in 1968, but the Monde Marie partied on. New clubs sprang up, with the Kāpiti Folk Club opening early in the year, the Port Nicholson Folk Club later on. The music was diversifying, with more British traditional music being performed, and bluegrass gaining national attention when The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band was featured on television. With import restrictions impacting the flow of music into the country, this band was instrumental in disseminating the latest bluegrass music, on 7” reel-to-reel tapes.

Above, from left: Alistair Hulett, Richard Doctors, and Sharyn Staley - Wellington Folk Festival Collection

On Sunday 31 August 1969 a combined meeting of the Wellington area clubs was held to discuss the establishment of a Wellington Folk Centre, merging the Wellington and Port Nicholson clubs to run it. On 12 October, the Wellington Folk Centre was formally incorporated as a society, with the Wellington and Port Nicholson clubs disbanding.

A group of Wellingtonians organised the first Traditional New Year Festival to kick off 1970, held at Taurewa on the edge of the Tongariro National Park. It was followed on 4 January by the Grand Opening Concert of the Wellington Folk Centre, at 41 Palmer St, Te Aro. Featured performers included Fyfe, Winnie, Jim Delahunty, Richard Doctors, and Ian Gorman. The Centre was well-used, open on Wednesday and Friday nights for instrument lessons and informal sing-arounds. Formal concerts were held on Sundays, with occasional special events on Saturdays. Attendance was so good there was often not enough room to accommodate everyone who turned up. The Centre was open each night of the Folk Festival for conviviality and jam sessions after the evening events had finished. (It continues to operate under the Acoustic Routes moniker, currently meeting at the Johnsonville Club).

Above: John Sutherland; Pat Bowley, Bev Young and Colin Bowley. - Wellington Folk Festival Collection

In 1970, the first overseas guests began appearing on the Folk Festival bills in the form of A L (Bert) Lloyd (English folk singer and folk song collector), and Irish expat Declan Affley (one of Australia’s most celebrated folk singers and musicians). Exposure to overseas guests has been an ongoing feature, with many famous names from around the world appearing. Saturday featured lectures and panel discussions. Nothing ran concurrently, and classrooms were set aside for different groups to jam and hui in, if they weren’t attending items in the official program. Saturday night, as was – and has remained – the custom, featured a concert. This rhythm of events and performances – coupled with plenty of opportunities to mingle and spontaneously jam – remains at the heart of the festival.

The festival was run by the Wellington Folk Centre from 1973.

Wellington Regional Folk Foundation committee member Mary Livingston first encountered the festival when she arrived in the capital from the UK, to undertake her PhD at Victoria University in 1976. Friends would join her, donning their hippie finery, and camping for the weekend.

“I absolutely loved the Ballads to Blues concert held annually at the festival … last night, usually followed by everyone meeting somewhere afterwards for mass singing with 10-part harmony,” she recalls.

Left: Paul Metsers, Janet McLennan, Vicki Smith, Bob Silberry. Right: Mitch Park, Arthur Toms, Steve Robinson - Wellington Folk Festival Collection

Livingston suggests advances in domestic and overseas air travel in the 1970s influenced the festival, by making it easier for people to travel between the North and South Islands for a weekend event and, later, also from Australia. Although the music evolves as new ingredients are added, it also retains strong threads of the timeless traditions that bind its adherents.

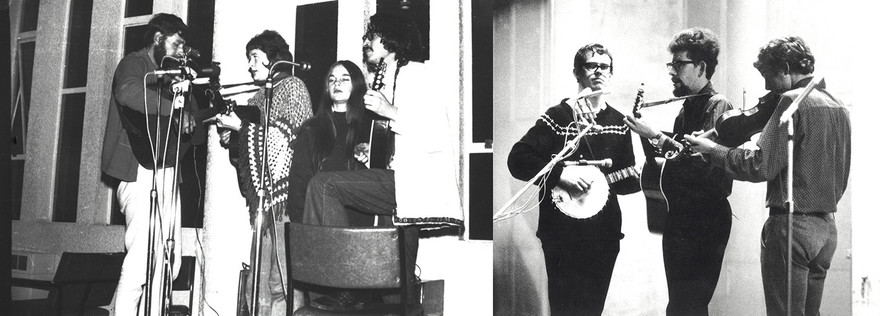

Sharyn Staley's programme for the 25th annual festival in 1989. - Wellington Folk Festival Collection

“There have been phases when we have been dominated by recent music in the folk world, and its reinterpretation. But then there are retro interests and early New Zealand music, for example, has re-emerged. Then, more recently, sea shanties and trad music. The sessions are now often mic’d up, which happened less in the past. Sixty years ago we were not in tents! That was fairly recent, but really took off when the festival secured loan of a large marquee in 2003. The festival became hugely popular as a result.”

The 25th anniversary of the festival, in 1989, was the first anniversary that was officially marked. Colloquially called The Golden Oldies concert, it showcased a range of acts who had played at one or more of the prior 24 festivals. Performers included: Metsers, Sutherland, Dave Hollis, Ron Craig, Dave Hart, Mitch and Robyn Park, Marg Layton, Frank Sillay, Robbie Duncan, and Alan Young. The festival also booked Australian folk singer/songwriter/guitarist Judy Small, for a packed Friday night concert.

In 1992, a separate organisation, the NZ Folk Foundation, was established to run the festival. It continued to be held on Queen’s Birthday weekend at various venues around town. In 1994, all stops were pulled out for the 30th festival, providing an all New Zealand line-up, with performers old and new. The Final Concert of that weekend included: Garland, Fyfe, The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band, The Windy City Strugglers, Rosa Shiels and Claddagh. The Hamilton County Bluegrass Band also played a special, standing-room only concert on the Sunday afternoon at Onslow College, which was recorded by Radio NZ and broadcast later in the year.

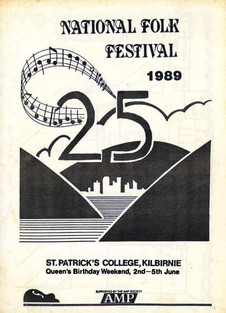

Above: Jo Taylor and Kayte Edwards, 1999 festival (both by Sue Hirst), and Marg Layton. - Wellington Folk Festival Collection

In 1996, the festival date was shifted back to the original Labour Weekend. The change of date was to enable a change to a camping festival, with the Brookfields Scout Camp becoming its new home. The move enabled people to stay overnight at the venue and meant that jamming and informal activities could continue as long as people could keep their eyes open. Several other folk festivals around New Zealand had been established by now, so the National Folk Festival was renamed the Wellington Folk Festival.

In the first years at Brookfield, the main concert was still held at a hall, firstly the Wainuiomata School Hall and thereafter at Wainuiomata College. In 2003, the hiring of a marquee meant that all activities could be held onsite.

Wellington Regional Folk Foundation President since 2023, Tony Burt (Argosy, Madlight, Across the Great Divide) is a musician and filmmaker well known in folk circles – and beyond – for his resonator guitar chops. He first encountered the festival around 2010, rocking up with his pup tent and first Dobro. He recalls: “Just soaking in the atmosphere, strains of bluegrass and morris, fiddlers and hurdy gurdy that permeated the grounds. Unfamiliar faces, many people that over the past 15 years have become my folk whānau and dear friends. Nowadays, on arrival, it takes many hours of hugs and banter just to say hi. That’s the fellowship.”

Cross-pollination between artists – both booked and ticket-bearing – is one of the festival’s most attractive aspects.

Above: the Gazebo Girls (Janet Muggeridge and Penny Bousfield), and Bob Silberry and Alan Young. - Wellington Folk Festival Collection

In terms of the sustainability, the trappings of popularity and success are also its biggest threat. “The marquees alone cost more than 60 percent of the whole festival,” Livingston points out. “The younger performers coming through have little income, as do the older retired folk who dominate the festival. The other important thing is keeping on top of technology … a lot of skills are required to ensure that the electrics, sound and light systems needed for the marquee [work].”

Nevertheless, she thinks the interest in music festivals, including folk, is here to stay. “More and more younger people are showing up, with some very fine performers,” she says.

In 2024, the Youth Performance Awards initiative – aimed at ages 11-16 and 17-25 – was investing in the growth of the future of folk music. Sponsored by the Walker Trust for Traditional Folk Music, participants were simply asked to: ‘Sing us a traditional folk song’; or ‘Play us a traditional folk tune.’ Cash prizes were on offer.

Livingston stresses how much effort goes into giving people a fair go – this is music of the people by the people, after all. Consequently, any one applicant cannot repeatedly perform as a highlighted guest, year after year.

International acts have continued to bring new fuel for the fire. In more recent years, Whitetop Mountaineers visited from the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia in 2012; the Danish band Himmerland – whose members hail from Chile, Denmark, Scotland and Chile – played in 2023; Australian Folk Music Awards Solo Artist of the Year, Fred Smith performed in 2024.

In 2025 the Main Stage guests will include Adam and Marika, Fiona Ross, We Mavericks, Klezmer Rebs, Rhys Crimmin, The Trenwiths, and Two if by Sea: Wellyfest shows no signs of slowing down or going anywhere any time soon. “No one expected it to run for 60 years!,” says Livingston, but the fire is still burning. What’s more, it’s made a home of its current venue since 1996.

“Jamming into the wee dark hours or until daybreak is a highlight,” Burt says, by way of explaining the draw to gather, year after year. “Your brain stops and the fingers take over … you stop only when the need for sleep becomes overwhelming. Wellington Folk Festival is more than just music, it’s a celebration of folk fellowship. A long weekend in which we come together as whānau, meet heartily on the field with old friends, and discover new ones. We share our stories, music, laughter and occasional tears, immersing ourselves in the warmth of community. The joy of music and dance gathers us, but folk fellowship is the essence that binds us. I would like to see that we collectively nurture and encourage the values and expressions of this tradition, ensuring that it thrives for generations to come.”

--

Wellington Folk Festival programmes, 1965-2010