For over a century Auckland was the main meeting place for blind and vision-impaired musicians. Until at least the 1960s New Zealand’s Education Department policy was to send children with impaired sight to the school for the blind in Auckland as a kind of insurance policy: to teach us Braille etc, just in case we completely lost our sight later. The state school system didn’t have the resources to cope well with minorities in those days. Consequently, the Royal New Zealand Foundation For The Blind became a big part of life growing up.

Jubilee Institute for the Blind, Parnell, c. 1915. - Photo by William Thompson, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 35-R0072

The “Foundation” school in Parnell was a Dickensian institution, with an 1890s Edwardian brick buildings, student dining hall, asphalt playground, grey uniforms, boys’ and girls’ dormitories. A pipe organ played English protestant hymns at assembly. A friendly place, though, with only 100 pupils – most of them boarders. I was a day pupil there in the early 1960s. It was good to be able to go home each night, but sometimes I wondered if I might be missing out on some exciting stuff by not living in.

Julian Lee was aged 12 when he toured New Zealand for three months with the Jubilee Institute for the Blind band in 1935. He is pictured here in the front row, at the far right. George "The General" Bowes, the bandmaster, is third from left in the same row. Along with the sight-impaired music teacher Vivienne Martin, Bowes was an inspiration to countless music students in the 1930s. - Royal New Zealand Foundation of the Blind

During the Depression years touring concert parties of Foundation performers were a major fundraising stream. Students were encouraged into piano and choir lessons, the brass band and girls’ string orchestra. “We used to say they weren’t any good, but they were,” said Lyall Laurent, jazz pianist.

The Station Hotel Quartet, with Lyall Laurent at the piano, far right, Brian Spence on drums, Stu Parsons on bass, and Morrin Cooper on trumpet and vibraphone. - Mark Laurent Collection

More or less everybody got a start in music, whether they wanted it or not. A number of accomplished church and concert organists learned their craft at the Blind Institute, including Joseph Papesch.

Joe Papesch, organist and father of Claude Papesch, was director of music at the Institute by 1957. - RNZ Sound Archives

“Uncle Joe” was Claude Papesch’s dad (and my godfather). Claude – also totally blind – was the pianist with Johnny Devlin and The Devils, and became a bit of a New Zealand rock’n’roll legend in his own right. “The Foundation over the years has produced some brilliant musicians,” says Ken Smith (saxophone, flugelhorn, trumpet, flute).

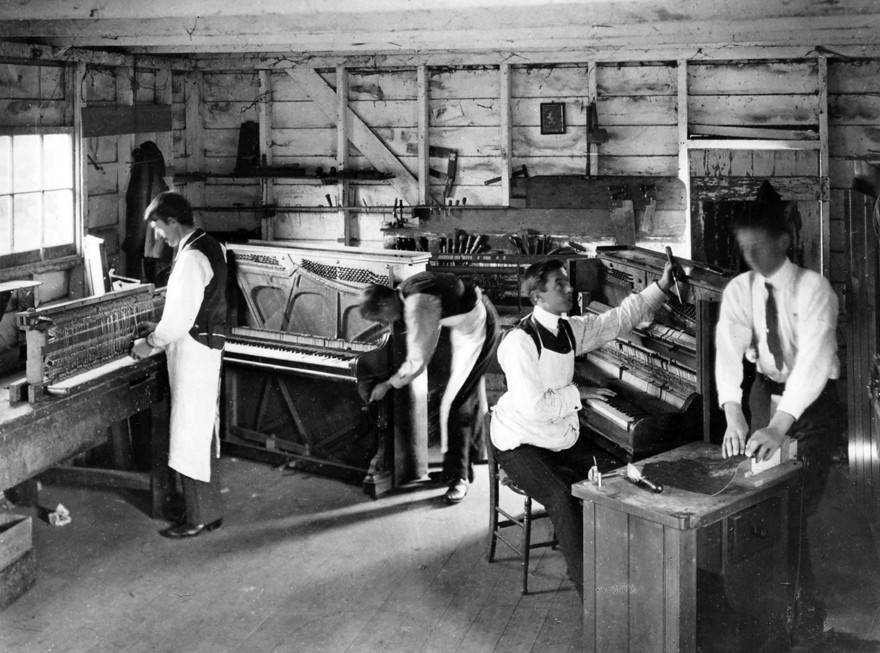

Piano tuners at the Blind Institute, c. 1920s. The Institute trained over 20 sight-impaired tuners after they became injured in the First World War. - Royal New Zealand Foundation of the Blind

Piano tuners – over 20 of them – were trained at the Foundation’s own workshop. My grandfather, Morton Laurent, was born with congenital cataracts (thus my connection to the blind community). Grandpa and three of his brothers became piano tuners, and it turned out to be a really good, independent profession for blind men. Tuning requires really good ears and a finely honed feel for tensions and balance. Also, most homes had a piano in those days so there was plenty of work. My grandma, Hazel, drove her husband to his tuning jobs, and helped him with piano repairs, the things he couldn’t see to do.

In 1964 the institute moved to Homai, South Auckland. This photo shows Homai College under construction in 1963. - Murray Freer Photos/ Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Footprints 06581

A 2021 photo of The Hub, part of the Outdoor Learning Environment at the Homai campus of BLENNZ (the Blind and Low Vision Education Network NZ). The garden has a compass in the centre with planter boxes around the outside. The different plants provide sensory and experiences for the sight-impaired students. - BLENNZ

Out of the classroom, sports presented difficulties for many, and as most of the kids were boarders, music became a large part of their social life. There were pianos in the common rooms and they got a lot of use. The school moved to South Auckland in 1964 and became Homai College. The strong music tradition migrated too.

These days Homai acts mainly as a resource centre as nearly all students are “mainstreamed” in the “sighted” school system.

Blind people often refer to each other as “totals” or “partials”

Blind people often refer to each other as “totals” or “partials”. Many “blindies” can see a little, even if it’s just awareness of light and darkness, or colour, and “partials” can see to a lesser degree the same things as sighted people can – although they may require thick-lensed glasses, large print or close proximity to objects to make use of the vision they have. A person is technically blind when their vision reaches an acuity of 6/60: that means that what most people can see at 60 metres, a blind person can only see clearly at six metres or closer. You’ll often see blind musicians wearing dark glasses. It’s probably not a badge of “cool,” but rather as protection against light-induced discomfort or to conceal cosmetic abnormalities (“funny eyes”), or occasionally, the absence of eyes.

I spoke to a number of sight-impaired musicians while putting this article together and, perhaps disconcertingly, several told stories of audience members (not all drunk) asking things like, “Can I look at your eyes?” Ken Smith, once asked this by a woman, responded with, “Can I feel your breasts?” “She said okay, so I lifted up my glasses while she had a look. I sort of forgot about it and reached for my drink. Then she grabbed my hand and said, ‘Here you are’. My mates never let me forget it!”

There are three particular challenges for blind musos – transport, moving on stage and reading sheet music. Haywood Amu plays drums and bass, and says, “Transport is our only real problem.” He knows blind musicians who’ve gotten help from WINZ to buy a van for work purposes – of course they had to find a driver too. Ken Kincaid (who works solo with guitar and drum machine) uses taxis and InterCity buses a lot, and likes to be assertively independent. When he gets gigs he tells them he needs somebody at their end to meet him. “There is rarely any problem if you explain your situation.”

In the early 1970s Ken Smith went on his own to Australia in search of work, ending up playing 18 months for US troops in Vietnam, and found people in Sydney so helpful, “I wondered if there was a lottery going if you help a blind person.”

The Radars: Neville Taura, Harvey Baker, Feau Halatau, Andrew Taylor, Ray Lemon

One of New Zealand’s longest running bands is The Radars. Feau Halatau (drums), Andrew Taylor (rhythm and vocals) and Ray Lemon (lead), all founding members, started gigging the traps (“We play everything”) since 1962. “We usually had a sighted muso to do the driving, or else our wives would drive us,” said Feau. “I have a bit of sight so everything (to do with organising) lands on me.”

On stage it’s all too easy to lose track of where the mic is, to stand on a guitar lead and pull it out, to kick in the distortion unit when you meant to hit the chorus, or to miss the edge of the stage in the semi-darkness. It can also be difficult to look right. Lynette Simon says, “If you’ve never seen someone on stage, waving their hands around, etc, you don’t know when to smile. If you turn around you think, ‘Oh God, am I facing the front?’” On the other hand, she says, “Advantages? Well, you can’t see the audience.” John “Lobby” Manchester (bass, drums) agrees. “I think seeing the audience makes you nervous.”

“If I hadn’t been to Homai I wouldn’t have had the piano and theory lessons,” – Lisette Wesseling (1971-2016, soprano, pianist, teacher).

Lisette Wesseling, a soprano, loved baroque music, sang lieder and successfully sat her ATCL qualification. She used Braille sheet music: “But you have to use two hands to read it and therefore have to memorise music before you can play it. It can be hard to get music in Braille, and conductors often have the choir and orchestra make pencil alternations on the score. I have to keep them in my head.” Lottie Trevarthen, who was a fine jazz pianist / vocalist, found it hard at music exams. “The sighted person just sat down and played. The blindie had to go to another room, figure out the braille and then play it.”

On the other hand, everyone I talked to said that imperfect sight tends to make hearing more perceptive. Lyall Laurent: “I made sure I could play everything in every key.”

The other thing is that everybody expects the blind musician to be “hot!” – audiences and sighted musicians alike. They’ve heard Ray Charles, Stevie Wonder, Jeff Healey, and Jose Feliciano, so ... “People always thought you were gonna be good,” says Lynette Simon.

Caitlin Smith, Auckland singer, vocal coach, and music writer

With other musicians it’s no problem as far as credibility goes, but blindness doesn’t in itself make you any better a musician than good sight does.

And sight impairment is a challenge for the sighted, too. “Because your eyes don’t focus they say, ‘Man, you must be high!’, and they want some of whatever you’re on,” says Ken Smith. “You’ve got to be really careful when people start buying you drinks,” says Lottie Trevarthen. As Ken Kincaid sums up, “You know people don’t mean to offend you. They are just not used to the world that you’re in.”

Blind musicians are all over the scene now, both here and all around the world. There’s no longer a central geographical place where they meet, as in the days of the Blind Foundation, but technology and changes in public perception of disability have opened the field in many aspects of life and most aspects of music. Names like Claude Papesch, Julian Lee, Richard Hore, Eddie Low, Jann Rutherford and Caitlin Smith are well known to many New Zealanders. I imagine you can think of a blind musician or two in a venue not too far from you. Don’t be shy to approach them; like all musicians, blindies love nothing better than a chance to share their passion and talent with anyone who’ll listen.

--

With research assistance from Tony Ricketts