Frank Gibson Jr was born to play the drums. Growing up in Balmoral, Auckland, he watched the Sunday jam sessions his father Frank Gibson Sr organised with his friends, Auckland’s leading professional musicians. Frank Jr’s career began at the age of eight, when he performed a drum duet with his father at the Auckland Town Hall. As a teenager he played in jazz and rock’n’roll bands, and his reputation spread around the world. In 1971, he helped form Dr Tree, New Zealand’s pioneering jazz-fusion band; in the early 80s he formed Space Case, which was more jazz funk oriented and recorded three albums. Both featured Gibson’s high-school friend, keyboardist Murray McNabb. Overseas he played on hundreds of albums, including sessions for Nat Adderley, Lee Konitz, Dusty Springfield, Dionne Warwick and many others.

This interview with Frank Gibson Jr was done at his home in Hillsborough, Auckland, in 2007, as part of the research for the book Blue Smoke: the Lost Dawn of New Zealand Popular Music, 1918-1964. Because of that, the conversation concentrated on the beginnings of his career, the 1950s scene, and the musicians who influenced him, especially his father.

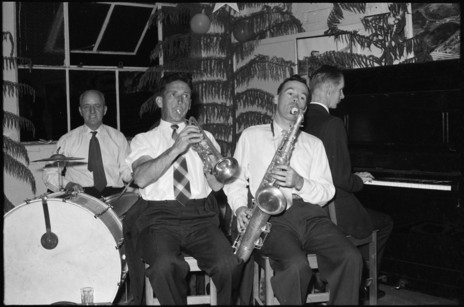

The Embers with Frank Gibson Jr. (right) in the mid-1960s. With Frank is bassist Yuk Harrison and jamming guest drummers Roger Sellers and Alan Nash. - Frank Gibson Jr. collection

Your first gig was as Frank the Boy Wonder in 1954 …

Yeah, I remember that. When you’re eight you’re so naive you don’t understand anything. Of course, walking on the Auckland Town Hall stage with my father to play a drum duet – which we’d worked out beforehand – was to me just like we were playing at home. I just walked out and did it. There were people then who were very worried about my nerves.I remember I played noughts and crosses with somebody before I went on and did that. I was calmer than I became much later, I became nervous. But [at that time], nothing. It was nice just to play, and I remember the audience applause.

Frank Gibson Sr and Frank Jr, Auckland Town Hall, 1954 - Frank Gibson Jr. Collection

They paid me – they bought me a portable radio for my room because they thought I was too young to be paid money. But later on, they paid me.

How did they treat you at school with all this going on?

Well, I was doing gigs while I was at primary school, and of course I was out late. One of the local schoolteachers at Maungawhau School, where I went, used to come and check things out: to make sure I was having a siesta, a nap, before I went out to play. Mr Snow – Trevor Snow. He’d come around and I’d be in bed, and he’d talk to mum, take a look and make sure everything was cool. But he was totally in support of it, of course. Some of the kids at school knew what I was doing but when you’re eight, it doesn’t mean anything to you.

The Juvenolians with UK bandleader Ted Heath. From left: Rodger Curtice (piano accordion), Bob Williams (piano), Ted Heath, Denis Duvall (trumpet). Frank Gibson Jr is in front of Heath, who said to Frank Gibson Sr that if he brought the band to the UK, a gig at the London Palladium would be organised. - Frank Gibson Jr. collection

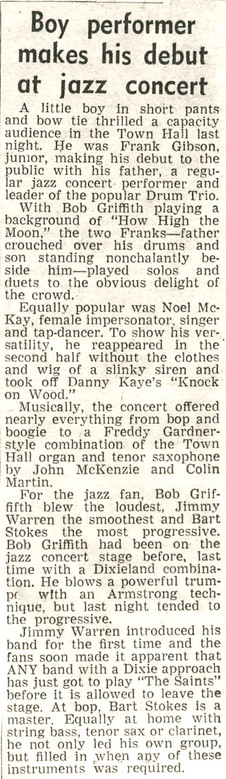

Frank Gibson Jr plays the Auckland Town Hall "in short pants" - Auckland Star, 20 September 1954

I didn’t know I was a child prodigy, which I was. And [visiting UK bandleader] Ted Heath invited Dad to take me to London when he heard me play when I was 10 years old. He said he’d put me on in the London Palladium, on TV, and make me the new Victor Feldman – a child prodigy in London. He worked with people like Cannonball Adderley, in the States.

But that was unheard of in those days, I didn’t even bat an eyelid at that. Mum and Dad were talking about it, and they didn’t even consider it either. It just wasn’t done, you didn’t do stuff like that in 1956.

In 1956 your father assembled the first New Zealand rock’n’roll band.

Yeah, Frank Gibson Sr’s Rock’n’Roll. I used to go with him on the Sundays to help pack up his gear at the Trades Hall [on Hobson Street], where they’d play on the Saturday beforehand. And it was smokey, drink and stuff, but it was a hell of an experience. When you’re so impressionable your eyes are wide open, you soak it all in, you don’t even know that you’ve done that until years later.

And that was my experience with the early thing with Dad. I knew that he was like a hero. New Zealand’s Gene Krupa, for sure. He was like a household name in this country as a musician. And that hadn’t happened before, particularly with that instrument. But he brought that kind of popularity to it.

Did he perform showcase pieces in that era, solos etc?

Yes he did. He played solos that I heard. Playing fast. Played a lot of rim shots on the snare drum, that always impressed people. I recall hearing Cozy Cole – [not just] ‘Topsy Part 1 and Part 2’ – but I remember hearing those when I was pretty young, 10, around then. Dad played things like that, but it was mainly solos in the form of a tune, like in a 32-bar song he’d play a chorus. But the crowd just loved him, he had a kind of charisma. He was a very charismatic man, I realised that later, but then he was my dad. That’s all.

What was his attitude to rock’n’roll?

He made one comment many years later in a magazine, he said when he heard ‘See You Later, Alligator’ he gave up music and started playing rock’n’roll. Which people won’t say today, but he was a straight arrow. He liked it, he cashed in on it, had the first rock’n’roll band, I remember it very well, he was also the first drummer in this country to play two bass drums. That was another thing. He backed Johnny Devlin …

The thing to remember of course is after Bill Haley came people like Fats Domino, Bo Diddley, the New Orleans people. Now, that music was great, but the white rock’n’roll music ...

To the swing guys, this was teenage music …

Yeah, but Dad was still young when he formed the rock’n’roll band. In 1956, Dad would have been 34, still a young man. But he got into it and did it properly, it sounded good.

Did he tell you about the Devlin sessions he played?

Yeah he mentioned that later in his life to me. He read something in a book once that said Johnny Devlin’s first backing band. The quality was questionable. But I know that the backing would have been very good, because it was jazz musicians, and there was jazz before there was ever rock’n’roll, and the jazz swing beat influenced the shuffles they played in rock’n’roll. They still had acoustic basses then too, Bill Haley’s band. Electric basses didn’t come till much later. The shuffle rhythm is a direct link, right back to New Orleans music, in 1916, the parade bands, that’s where the shuffle comes from.

I’m told New Zealand drummers struggled with shuffles …

But they did it later on. Claude Papesch did, he could play R&B. He was in a band we had, a kid’s band, and the old boy stole him and put him in his band. And we were really pissed off, even though I was only about 10 or 12 years old.

Claude Papesch at the piano, as part of a quartet playing at Henderson and Pollard Ltd's Christmas Party in the staff dining hall, 1959. - Rykenberg photo, Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections 1269-B0135-17

What sort of gigs did you do with Claude at that time?

Saturday night dances, when I was 10, 12, 13 – going right out to, like, Dairy Flat, doing stuff there, going to South Auckland playing gigs, and concerts with my dad. And The Juvenolians, the kids’ band, that was in 1956, the same year Dad formed the rock band.

Claude was in a band I had later on, not for very long. Dad got him when he was 14, because Claude could play alto sax and was a great piano player. He was one of the first sincere R&B guys here. I didn’t know that until I was much older and played with him.

What was Claude’s first instrument?

Piano. But he could play alto, he was like Ray Charles, New Zealand’s first Ray Charles. He was very close to that. So his R&B roots – he had a feel alright, the genuine New Orleans thing.

What was Claude’s personality like?

Claude Papesch, circa 1965 - David Ross collection

Oh, he was totally interesting. A blind guy. He used to mow the lawns in his bare feet so he could feel where he’d been. He and his dad used to do the dishes – he was blind too – and their mum was sighted. I remember walking round to their house in Haverstock Road, Mt Albert. And he used to walk round to Denis Duvall’s place – the trumpet player, when we had the Juvenolians, so the connection with Claude goes back that early. Then Dad took him off us, and we didn’t know what was going on anyway. That would have been for a rock’n’roll band, but it would have been after 1956. Claude was about 14 when he went to Dad.

That’s how he would have ended up in the Devils

That’s right. I was still doing other kids’ things.

What kind of gigs did the Juvenolians do?

We did concerts, jazz concerts. Town Hall concerts and gigs. We’d go to Thames and play the RSA, and stay overnight. It was jazz material but we didn’t have a bass player. It was an odd lineup, piano accordian, piano, drums and trumpet. But Denis Duvall ended up in Claude’s major R&B bands from that time. He was a great trumpet player, but he never was professional. Claude did this thing with a lot of great musicians, and he had backup singers, it was just like a Ray Charles thing. It was that good.

A 10-year-old Frank Gibson Jr. with his band, The Juvenolians. From left: Rodger Curtice (piano accordion), Frank Gibson Jr, Bob Williams (piano), Denis Duvall (trumpet). - Frank Gibson Jr collection

I went to see him – after he played with me, when I was younger – I can’t remember what year, it was after Devlin. He had a great group, with backup singers – Lottie Latimer, who was Derek Neville’s partner. He was a baritone sax player that came from London, with a hell of a reputation. When Duke Ellington went to London, he was asked to comment on what he’d liked about London. And he said, “tea and Derek Neville.” He came out here to live, and I remember when I first started playing with him it was a hell of an influence. Baritone sax, but he played them all, probably clarinet too.

[A sudden aside] “If you see a dead frog on the road, and a dead man, what’s the difference? Well, the frog’s probably on the way to a gig, and the dead guy is a trombone player.”

Your Dad got quite serious about drummer jokes …

As in, he was insulted, as a musician who played the drums. It’s like the old drummer jokes became bass player jokes, then they became trombone jokes.

Derek Neville stayed out here until he died. He used to live in the same street that Crombie [Murdoch] lived in, in Herne Bay. Wharf Road. That’s where Derek lived with Lottie [Latimer], who was a backup singer in Claude’s band.

This would be around 63, 64 – the Picasso was going, the Montmartre was going – that was my first professional gig. Mike Walker was in the Montmartre for a long time.

It was an older, hipper crowd than that for rock’n’roll?

Absolutely, no teenagers – but the same guy was selling illegal booze to the guys who went to the Montmartre as went to the Embers – Happy Jack. He was making a living selling illegal spirits and stuff because it was still six o’clock closing. He used to drive around with a boot full of it, and when I was playing at the Embers when I was very young, we used to buy our Scotch off Happy Jack as well. My Dad had done that a generation before. We’d mix it with Coke, a waste of good Scotch but we learnt better later.

The Montmartre was very hip. Murray McNabb and I had a band at school, a jazz group, when we were teenagers. I had a set of drums at school that just stayed there, and we used the science lab, and there was an upright piano in that room. So we used to cut classes and go in there and play, McNabb and myself. I remember one of the teachers coming in one day and saying, “What are you guys doing?” We said “rehearsing for the school concert” – and it was about March, and the school concert was in November.

[Back to the inner-city clubs] We used to go and watch Mike Walker, Les Still and Tony Hopkins, they were our heroes. McNabb and myself, when we were still going to school. We would go and watch the first set in the Montmatre, two or three times a week, then have to get back and do our homework and be at home by 9/9.30pm. After that it used to become more commercial, so we got all the jazz in the first set. Real serious shit. Mike was like a hero to us. And so was Tony Hopkins – he was a huge influence on me. I told him later and he wouldn’t wear it. He said “You’ve gone much further than I have.” But I said, “Yeah but if it wasn’t for you, I wouldn’t have done anything.”

Can you mention any other drummers in Auckland at that time ...

Owen Kneebone was one of my dad’s greatest students, also Don Smith, who was also in the drum trio early. They used to worship my old man. Dave May was another one, he is in Sydney now.

If the Montmartre had jazz early in the evening – what was the commercial stuff later at night?

We were reading Downbeat and giving each other blindfold tests when we were 15, 16 – we thought we knew a lot then. But as soon as they started playing stuff like bossas, bossa novas, easy listening …

You’d bail – the visiting vocalists came on …

Yeah, they used to have floorshows, stuff like that. I remember backing Marlene Tong when I first got together with Mike. In 64, a great singer. And Les Still was still playing bass in the band.

Marlene Tong, in scarf, relaxing at the Tauranga National Jazz Festival, 1965; bassist Les Still at right.

You have such a strong connection with several eras, including your predecessors …

We had respect for the guys who came before us. And people that my father respected had a lot of respect for him, too. Later on, the political crap came in. It became competitive rather than cooperative. But it’s always been cooperation with the drummers. Not so much now, I’m afraid. But when I was coming up, I loved all the drummers I heard, and I always liked to play like them, Tony Hopkins, Lachie Jamieson.

The first taste I had of bebop was recorded music, and people like Lachie. He played great vibes too, so I used to take my drums around, and he’d play vibes and I’d play drums, Denny Boreham played bass – and then he’d tell me what to play on the drum set, how to play bebop.

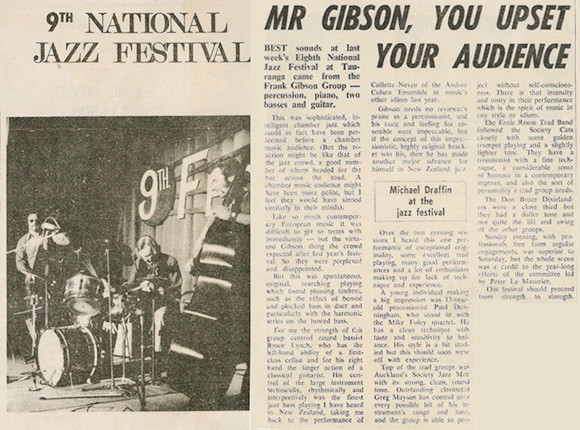

Frank Gibson Jr at the Tauranga Jazz Festival. Left: in 1971 with bass players Andy Brown and Bruce Lynch. Right: in 1970 reviewer Michael Draffin found the Frank Gibson Group's material too challenging.

Both your father and Mike Walker’s father came from Thames ...

My dad played with his band, that was the first band he ever played in, in Thames. And my dad’s brother Jim, my uncle, was the piano player in that band. And I used to see Mike when I used to go to Thames in my school holidays. I didn’t speak to him then because I didn’t know him, and we were too afraid then to say hello. Until later. Too shy. Same with Andy Brown when I first saw him. I thought, man, that guy’s so good. I told Andy later on when we were playing together, I said I was in awe of you, and so in awe that I couldn’t even come up and say how great I thought you were.

Don Branch I knew when I was very young. He was encouraging to me, and a great drummer too. He was like one of Dad’s era, but a little younger.

They worked in with each other, thanks to the Musicians Union – “I can’t do this gig, you do it.”

That’s right, the camaraderie that went on between the musicians makes what went on later ridiculous. Those guys had so much respect for each other, and they learnt off each other.

I saw that happening when I was a very young boy, and I didn’t realise what they were doing at the time, but they were all totally supporting each other and I was gleaning this knowledge from being around the house, I didn’t even have to go anywhere.

But I remember Dad used to take me to sessions at 1YA, when I was about six or seven, and I’d take my drumsticks everywhere, so when they were doing their thing, I’d be playing, hitting the chair – though when they were recording, I was quiet. They’d say yeah, you’re doing well. I had encouragement from most people. When I played at eight, Neil Dunningham was very helpful.

So you didn’t swagger round like a child prodigy

No, I was unaffected by it, thankfully. I didn’t even know. I read something years later where Neil Dunningham said, “His efforts are prodigious”. And I thought, Oh yeah, that’s what I had, the child prodigy tag. But it didn’t go to my head. I lead a relatively normal teenage life, played cricket and soccer with my friends, and playing gigs on the weekend, and being in a rock’n’roll band before I left school, all of that.

We used to play the Mt Albert War Memorial Hall, with a rock’n’roll band that Brian Henderson had. Now Brian was a piano player in Rodger Fox’s band, he’s still with Rodger, he’s been with him for years. At the War Memorial Hall, and the Hell’s Angels used to come along to our gigs, because they liked us. They existed then, I went to school with the head of the New Zealand chapter of the Hell’s Angels, in history class. He became that later on, he wasn’t when we were going to school.

Did you get involved with any of the 1960s rock’n’roll groups?

Yeah, sure, I was in one with Gray Bartlett, and we did private gigs in Remuera, and I remember stealing cigars from the people. The first recordings I ever did, I was just out of school and that was The Munsters theme with Gray Bartlett. At Saratoga Avenue, under Eldred Stebbing’s house before he even had the studio on Jervois Rd.

And my dad did jingles for Eldred, and I know that because of the stories Eldred used to tell me. They used to stay there for hours to get the perfect product, and he really didn’t know why we were that different. We’d go in and try and get it done as quickly as possible, because it was money for us. Those people were never professional musicians. And I’ve got nothing against that at all, I have only praise for those people who worked with my father in that era, they were great musicians but they had to work day jobs, too. We didn’t. So we’d go in there and in the first one or two takes, we’d get it. Or try and get it. And Eldred used to remind us of the pride that my father had in making a commercial.

But I remember doing that thing with Gray Bartlett because I had a friend at school that liked to play the tambourine, and I told Gray that this guy was a percussion player, and he wasn’t, he just my buddy. And he came on and he played tambourine on this track, and halfway through it his right arm got so tired he had to stop and use his left hand. Things like that went unnoticed. I was playing rock beats then.

I also played with early guitar players too, I played with Dave Donovan, who was a great jazz guitarist. He used to memorise Barney Kessel songs note for note, and I played with him in the 60s. And then he went to Sydney and became a huge studio musician. He’s dead now. He was a big influence on all of us, too.

Sunday jam session, Epi Shalfoon band, early 1950s: Jack Clague (trombone), Julian Lee (trumpet), Frank Gibson (drums), Bob Ewing (bass), Allen Posley (piano), Ray Gunter (guitar). Bandleader Epi Shalfoon was Frank Gibson Jr's godfather. - Frank Gibson Jr. Collection

Did you witness any of your father’s Sunday morning jam sessions?

I remember my dad ringing people up … there’s a story of my dad calling up [bassist] Bob Ewing for a jam session on Sunday, and his mother said to Dad, “Oh Bob’s at church.” And Dad didn’t know he had any affiliations. But he then became “the Reverend Bob Ewing,” and later “the Reverend Bob Spewing.” True story – Bob told me that himself.

So they were jamming a lot. I went to some of them. There was no jamming going on in our household, there was just a lot of people listening and playing poker and drinking, hanging out.

So you had lots of musicians coming round, socialising?

Oh yeah, absolutely. There was always music stuff happening in our household. There were musicians coming round to play poker – Bobby Griffith, Bob Ewing, Nolan Rafferty. We were in Balmoral. They’d come on Sundays too and play the new albums. Drummers were coming round all the time, like Don Branch, Barry Simpson, who used to write me out little exercises, and I’d hum them to him. Those were the first lessons I had, other than a few with Dad. These people were totally encouraging to me when I was eight years old. Dad, too: I was learning off him from the age of six.

Formal lessons?

Yeah. I sat with my practice pad, and he sat with his practice pad, but there was no [sheet] music involved, it was rote learning, he would spell the sticking out for me for a certain rhythm, and say “play slowly and evenly”. That was always what he said, it was a very correct way to teach – but it was all by ear.

--