5 – Badger the Boxer Loses His Head

Ken Badger was quite different to the other residents at 57a, not just in temperament, but in working habits. He got up early each morning as carpenters do, to go off to work, whereas the musicians stayed up until very late at night, often drinking and playing records and making a bit of noise in the process.

And there was the problem: Badger was permanently aggrieved at being kept awake and decided to retaliate in kind, thus triggering off a dramatic chain of events which could end only in a parting of the ways.

On rising at some unnatural hour of the morning, Badger would turn on his radio loudly and stamp up and down the hall to and from the bathroom, while sometimes whistling and singing as well. Behind the thin walls, Bennie opposite, and Choc and Lachie nearby, would suffer this racket – sometimes only a few hours after getting to bed themselves. After a few days of this, something had to be done.

During one day, Bennie climbed into the ceiling to divert the wiring to Badger’s light socket (which also powered his radio) so that Bennie could control the power going into Badger’s room. By installing a thermal flasher, he arranged that every time Badger turned on the light or radio, after a short time his light would flash on and off and the radio would make a terrible noise. When Badger dashed out to find what was going on, everyone solemnly assured his that they were having the same trouble, and the house wiring or the Power Board were to blame. Everyone except Old George that is, who considered that whenever there was trouble, the musicians were surely at the bottom of it.

Bennie Gunn's ham radio station, 57a Symonds St Auckland. - Merv Thomas Collection

As a result, the radio in the mornings was turned up louder than ever. This time, Bennie built a random noise transmitter which he could control from his bedside. Whenever Badger stamped up the hall with his radio blaring, Bennie turned on the transmitter, and the radio broke into the most terrible static, mixed with an oscillation which threatened to blow the radio apart. By the time Badger tore back from the bathroom the radio was playing sweetly, only to burst into spasms again as soon as he closed the bathroom door.

After he had furiously stamped off up the path to work, Lachie was seriously concerned, and tackled Bennie. “He’s a real mean son-of-a-bitch, man,” said Lachie earnestly. “When he figures out who’s responsible, he’ll make mincemeat out of you. He’s a champion boxer!” “Okay, but do you want to listen to that racket every morning?” Bennie asked. “Why don’t you ask him to stop!”

After a few more mornings, some without the oscillator, and others promising sudden death for Badger’s radio, his suspicions turned into action, and he bashed furiously on Bennie’s door.

“I know it’s you, you bastard! You’re to blame for stuffing up my radio! If you weren’t locked in there, I’d drag you out and kill you!”

Bennie expected the door to splinter any moment, and slid further under the blankets, hoping fervently the madman outside wouldn’t try the handle, as he, Bennie, had neglected to lock it the night before. After a few more shouts and bangs, Badger stamped off down the hall, and set off for work.

The following night, Bennie was hard at work in the basement on a makeshift assembly operation, putting together cabinets for his first order of guitar amplifiers. As he hammered away, after even the musicians had gone to bed, a wild-eyed figure dressed in pyjamas appeared at the door. “What the hell do you think you’re doing?” shouted Badger. “Working of course, what does it look like?” “Working?” Badger was still shouting. “Do you know what the time is?” “No,” answered Bennie. “It’s half-past two in the bloody morning!” “Yeah, well, thanks for telling me,” replied Bennie. “It’s time I knocked off.”

“You’re crazy!” said Badger. “Completely bloody crazy! I’m going to sort you out, just wait and see!”

Badger stared wildly. “You’re crazy!” he said hoarsely. “Completely bloody crazy! I’m going to sort you out, just wait and see!” He turned and strode off.

The following evening Mr Sussex appeared and spent a long time in Badger’s room. When he reappeared, he knocked on Choc’s door.

“Mr Leemon, I’ve had a serious complaint I’d like to talk to you people about. Are the others at home?”

Lachie was already in Choc’s room, and Bennie, working next door, was called in. When they were seated, Mr Sussex began.

“As I’ve told you before, gentlemen, all I want is for everyone here to have a fair pop, and to work together. Mr Badger doesn’t think he’s had a fair pop at all; he’s been frequently kept awake late at night, his radio has been howling and crackling, his lights have been going on and off, and last night Mr Gunn was hammering and banging till two-thirty in the morning. Now, I don’t like having to come down here at night to hear this sort of thing, and to be fair, would like to hear your explanation before I take firm steps to solve the problem.”

After a long pause, Choc was the first to respond. “Well, Mr Sussex, we’ve been rather concerned about poor Ken ourselves. We’ve had no trouble with the lights, which are quite normal as you can see. As for the radio, it’s hardly our responsibility if he has a faulty radio – we can’t be to blame for that, surely?”

“Perhaps not, but what about the hammering in the early hours of the morning, Mr Gunn?”

“Does that sound reasonable behaviour to you, Mr Sussex?” inquired Bennie. “Does it sound likely?”

“No, it sounds preposterous!” said Mr Sussex. “But ...”

“If it was that noisy, I’d have been kept awake too,” chimed in Lachie. “I didn’t hear anything, and I’m right above the basement. Has anyone else complained?”

“I didn’t complain, because there was nothing to complain about,” replied Choc, gravely.

Mr Sussex was nonplussed. “That’s all very well, but Mr Badger couldn’t have made all this up, surely?”

“Ah,” said Choc solemnly. “That’s why we’ve been worried about him, you see. You do know he does a fair bit of boxing?”

“Why, yes,” responded Mr Sussex. “He’s rather a champion, I understand.”

“Well, you know what sometimes happens to boxers when they have one too many blows to the head. They become quite unpredictable, and ...”

“Punch-drunk!” suggested Lachie. “And Ken has been as you know behaving strangely, stamping around and singing loudly very early in the mornings for some time now, so you see why we’ve been concerned for him.”

Mr Sussex looked stunned. “You really think he’s been – affected – and has imagined all this?”

“The classic symptoms are all there,” said Bennie. “I’m sure if he’d only give up boxing for a while, he’d become his nice normal self again.”

“Goodness!” said Mr Sussex. “This throws a different light on the matter. I’m sorry to have troubled you all, and I am touched by your concern for your fellow man. I’d better see if I can help the poor chap. Will you be here for a while?”

“Unfortunately, we all have to go out shortly for an urgent appointment,” replied Choc, “but we’ll be here tomorrow if you need help, I’m sure.”

As Mr Sussex went in to counsel Badger, Lachie, Choc and Bennie quietly made their way up the path to the pub, out of harm’s way.

Badger’s door flew open, and a wild figure danced out, fists at the ready.

The following afternoon, Bennie was the first home, closely followed by Lachie. Before they had time to settle in, Badger’s door flew open, and a wild figure danced out, fists at the ready.

“I’ve been waiting for you bastards!” he hissed, bouncing on the balls of his feet. “So, I’m crazy, am I? I’ll show you how bloody crazy I am! Put your fists up!”

He danced around the hall, throwing vicious hooks at Bennie, who defended himself as best he could, but was able to inflict little damage in return. Lachie hid behind Choc’s door, poking his head out at intervals to shout “Peace, man, Peace!” then ducking back behind the door. Badger weaved back and forth, snarling and punching, for some time until finally with a sharp punch to the jaw, sent Bennie, bloodied and bruised, crashing to the floor.

“How’s that, then!” called Badger triumphantly. “Had enough? Get up, and you can have some more!”

“All you’ve shown,” replied Bennie from the floor,” is that you’re a better boxer than I am. We all knew that anyway, so what exactly have you proved?”

Badger glared, then with loud curses stamped off and slammed his door behind him. Lachie came out and surveyed the damage. Bennie stood up and put a handkerchief to his bleeding nose.

“You were a great help, weren’t you?” he said bitterly.

After that, the fight went out of Badger. He soon announced that he’d found somewhere else to live, and moved out, unlamented even by Mr Sussex. He was replaced by sax player and trainee lawyer Pete Robson, and now with a full house of musicians (except for Old George, who was deaf anyway), the age of dissent was over.

6 – The Urban Lifestyle – 57a Version

The cuisine at 57a would be best described as rustic/Wattie’s survival food. The bachelor musicians were not gourmets by nature; the menu of the few married couples living there from time to time is unknown, but a wife had to be a tough pioneer and preferably deaf and blind to survive there. Cooking was confined to a gas-ring in each bedroom, there was no kitchen, no refrigerator, and the “laundry” was a leaky agitator washing machine which drained onto the ground and had a wringer which worked occasionally. The laundrette up the road was well patronised.

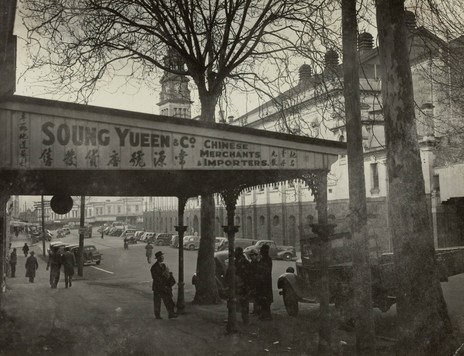

Greys Avenue, Auckland, 1940s, showing the back of the Auckland Town Hall and Chinese merchants Soung Yueen & Co. In the 1940s and 50s there were several Chinese cafés and businesses in the area. - Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections Footprints 02487

There were no great restaurants in Auckland in the 1950s, when a top-shelf nosh-up would be a combination grille with Worcester sauce at the Victoria Grille, accompanied by bread and butter and a muddy liquid known as Brown Barrett’s Coffee and Chicory. That would be well beyond the budget of any 57a resident, to whom roast beef and Yorkshire pudding at the Star Hotel was worlds away, and for whom a luxury would be fried rice or chop suey with meat of doubtful origin at the Golden Dragon or Guam Liang cafés in Greys Avenue, opposite the Town Hall.

Fast food hadn’t yet been invented, so cooking was a do-it-yourself affair, the menu being either baked beans on toast, spaghetti on toast, poached eggs on toast (Bennie Gunn’s staple diet), and on special occasions both spaghetti and eggs. Val “Choc” Leemon’s speciality was Wattie’s cream of sweet corn on toast. Shopping was done most days from a dairy nearby – where the Sheraton now stands – as, without a fridge, food had a limited life.

Led by “drum major”, bassist Les Still, the Auckland Jazz Club band escorts the Kenny Ball Band past the Picasso on Grey's Avenue, Auckland, to the Monaco on Federal Street, 1962. - Neil McGough Collection

The benefits of shared crockery and utensils meant a lot of the cooking was done in Choc’s room, even by visitors, as he at least had shelves for the essentials, and a sink where the washing-up was reluctantly done whenever the crockery or pots ran out. The guests were frequently the butt of Choc’s humour: on asking a silly question, such as where the salt or the teaspoons were, they would get the response: “In the tin, of course.”

“Which tin?” they would ask innocently.

“The tin that Rin-Tin-Tin shit in!” Choc would answer, laughing uproariously.

The supply of liquor received much more care. The staple diet was beer in quart bottles or in flagons filled at the pub up the road, half-gallon flagons of wine from the vineyard in Oratia, and Pimms No.1 as a concession for lady guests. Any spirits were a luxury brought to parties by visitors and left behind.

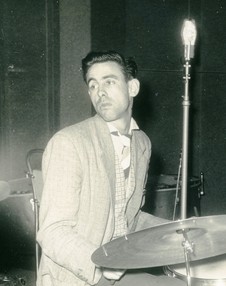

Lachie Jamieson, 1950s - Dennis Huggard Archive, Alexander Turnbull Library, DHA MS-Papers-9018-45

Lachie Jamieson would go to any lengths to acquire grog. Bennie had played at so many Doo family weddings at the Farmers’ lounge he could almost play the Chinese national anthem right through. At this wedding, he had Lachie playing with him and they were extended the usual lavish Doo hospitality, with a long row of beer bottles under the piano. Nevertheless, Lachie decided to take as many bottles home as he could carry, and concealed them under his enormous army greatcoat which he always had with him for sleeping rough. He held them in place with arms clamped to his sides.

The band was extended the same courtesy as the guests of being farewelled by Tommy Doo Senior, who insisted on shaking hands. At Lachie’s turn, his grip on the bottles was lost, and they tumbled from under his coat onto the carpet. Tommy Doo merely smiled and told Lachie: “I’d be delighted if you would take our refreshments home. Please allow my son to carry them to your car!” As Norman picked up the beer and added more from under the piano, Lachie was, for once, quite speechless.

Parties at 57a would frequently carry on late, with music at all hours. Whereas locally available and popular records were by the George Shearing Quintet and Billy Eckstine, Lachie had brought records back from United States which played and played: Miles Davis, the Modern Jazz Quartet, Sonny Rollins, Gerry Mulligan, and Max Roach became a permanent background.

Choc was a genial and generous host, and even when at a late hour his lady friend would yawn theatrically and put her diaphragm on the bedside table, the hint would be generally ignored by all present whenever a party was going on. There were parties in other rooms as well, and frequently, visitors would contribute to the hilarity. On one occasion, Ron Polson and Anna Hoffman arrived to celebrate in a way which raised even the tolerant behaviour (and noise levels) of 57a to dizzy new limits.

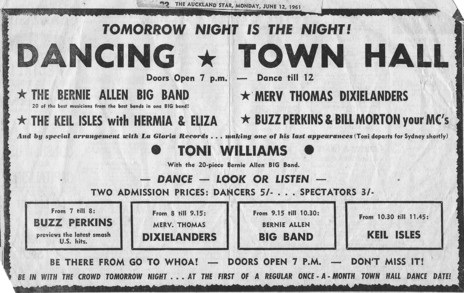

Tuesday night in the Auckland Town Hall, June, 1961: The Bernie Allen Big Band, Merv Thomas and His Dixielanders, The Keil Isles, plus Toni Williams. - Bernie Allen Collection

Choc was so obliging that on Sunday mornings the Bernie Allen Practice Band – all 14 of them, including many residents of 57a – would cram into his room to rehearse all morning. First though, there was the matter of access to his room. Frequently, the band would have a lengthy wait crammed into the hall until Choc had risen and dressed, then pushed out a lady companion who would have to thread her way through these players to reach the front door, her ears sometimes reddened at the ribald comments. Then the rehearsal could begin. There was no sleeping through that for anyone, though even members of the band sometimes looked ready to pass out or fall asleep.

Bob Elliot was a Scottish trumpet player who moved in for a short period. He was remembered, not for his trumpet playing nor the fact he had a very short fuse, but for his generous offerings of cups of tea. No one could understand the strange taste of his tea, until it was revealed that his staple diet was boiled eggs, and with canny Scots economy he would use the same hot water to make the tea. Demand rapidly dropped off.

The food situation changed when Pete Robson moved in. His parents called on him soon after, and were so horrified at the conditions they found that they made him promise to keep himself well nourished, and provided him with some of the raw materials. Every Monday, Pete made a monster stew in a large stockpot on his gas ring, which he willingly shared; there was enough for Tuesday, then for Wednesday. By Thursday it was thick and gamey, and by Friday extremely strong and almost solid. At first, he had willing takers glad of the variety in their diet, but as the week progressed, his custom declined noticeably. Even Wattie’s cuisine seemed a welcome relief. After the first month, Pete had his week-long stew all to himself and whichever of the long list of companions he had invited home.

Merv Thomas and the Dixielanders, Crystal Palace Ballroom, early 1960s (L-R): Clive Laurent, Merv Thomas, Tony Ashby. - Merv Thomas collection

The day Merv Thomas arrived to live with his new bride Carol, his temporary accommodation was in the basement. It had been forgotten that in heavy rain, water rushed down the path past the house and veered through the basement door under the duckboard floor. That day, it really poured, and by the time the lake in the basement had covered the legs of their double bed, Merv decided it was time they got out and stayed with his uncle till the weather cleared. Though they later moved to an indoor room, their six-month stay was a memorable introduction to musical married life.

Using today’s standards it’s easy to assume that the people at 57a lived in primitive conditions in great hardship. This never occurred to them at the time: they considered their situation as one of great comfort, if not luxury, and the freedom and company was well worth the occasional hassle. Full-time music was almost unknown – even Crombie Murdoch, more employed than most, was reading gas meters. Hand-to-mouth living was the norm; there was always another meal around the comer.

7 – The Not-So-Gentle Art of Music Teaching

The Studio was a small room at the end of the hall, next to the bathroom. Hardly big enough for a bedroom, there was barely room for a piano, a table and a few chairs, and so it had been designated a “studio”. It was long used by Pem Sheppard for teaching music; he lived on the premises in the middle bedroom with his wife Ione, a strong attractive woman with flaming red hair. Pem was not only a skilled performer on sax and clarinet, but well versed in music theory, and highly regarded as a teacher by his pupils. He had two major drawbacks however: he was confined to a wheelchair, and he enjoyed making serious inroads on the plentiful supply of liquor he kept hidden under the blanket on his wheel chair. He was hospitable to a fault, and would readily invite friends to help themselves to a bottle. However, as he would also relieve himself under the blanket into empty bottles and then replace the cap, friends would have to be wary of which bottle they selected.

The first drawback, that of mobility, was largely overcome by Ione, whose enormous strength enabled her to push Pem and all his gear up the steep path, aided by a long rope and pulleys attached to the fence, and a volunteer to push the wheelchair while Ione pulled. Once up on the street, she loaded him in the front, and his chair in the back, of their temperamental Bradford van which was their sole means of transport to get to his many playing gigs. The second drawback, the drinking, was one even Ione couldn’t control, and it led to many legendary incidents, and ultimately to his demise. One such incident, outside the Peter Pan Cabaret after a ball, led to Pem careering in his wheelchair out of control down Queen Street, with a whole bevy of people chasing him down the road to try and catch him before he reached the Town Hall.

Mt Maunganui, c 1955-56 (L-R): Merv Thomas, Lyn Christie, Pem Sheppard. - Merv Thomas Collection

One night, at the top of the path while Ione was temporarily absent, Pem, in his cups, decided to negotiate his own way to the house. Inevitably, he lost control, and the wheelchair took off down the path, veered into the wall and tipped Pem helpless into the middle of the path. No one was there to help him, except Amy who came down the path soon after.

Amy was a widow pensioner who lived in the outhouse with Gibbo, and imbibed almost as much as he did. Whether they lived in drunken harmony or bitter enmity, nobody knew, as there was evidence both ways, judged by the shouting and screaming which often filled the air above their outhouse. On this occasion, Pem was grateful for salvation from any quarter and called for her help as she weaved her way past.

Amy sniffed, and after a glance merely kicked the prone figure and went on home, leaving Pem sprawled on the path.

Sometimes, even Pem’s friends showed a perverse disregard for his safety. “Dreamboat” (trumpeter Dave Ironsides) occasionally tired of pushing Pem down the path, and let him go half way down. By the time his chair, at great speed, hit the concrete veranda in front of the house, Pem – screaming at the top of his voice – would go flying through the air to land sprawling in the shrubs and lank grass below, his bottles peppering the ground around him. Miraculously, little injury seemed to result, and “Dreamboat” would laugh himself silly.

Eventually, the path became too much for even Ione to cope with, and she and Pem moved to a large house in Grey Lynn; at the same time, they traded in the ailing Bradford for an enormous old Hudson Straight Eight. Bennie Gunn moved in about this time and took over the studio to begin teaching piano, bass and guitar. It is an adage among teachers that 80% of pupils will always be hopeless. In this case, the other 20% seemed to be missing as well. One pupil was a wharfie who had never played before.

“I want to play the piano like Oscar Peterson,” he announced.

“Really?” said Bennie. “How long do you plan to practice?”

“Oh, at least an hour each day when I get home from work,” said the wharfie.

“Oscar Peterson practices at least six hours a day, even now,” Bennie pointed out. “How long do you think you’ll take to learn?”

“Well, I’ll give it about eight months,” said the wharfie. “If you can’t teach me to play just like Peterson by then, I’ll have to have another look at it.”

An aspiring bassist arrived for each lesson with his bass strapped on the back of an MG sports car

An aspiring bass player wanted to play like Ray Brown, and arrived for each lesson with his bass strapped on the back of an MG sports car his doting parents had bought him.

“Just listen to this,” he would enthuse, playing a meaningless string of notes which he said was a lick of a favourite tune.

“But you haven’t learned your hand positions,” Bennie pointed out. “I asked you to learn to play a major scale. Can you do it?”

“Nah, not yet – that’s pretty dull stuff,” said Ray Brown. “But I’ve got some great ideas I want to play you.”

“Your ideas are worthless until you learn the basics – how can you express them?”

Ray Brown grumbled at his imposed workload. After him was a guitarist who yearned to play jazz and wanted to learn harmony, but who had absolutely no sense of time. In between lessons, Bennie would hide in Choc’s room, cooking poached eggs on toast.

“Perhaps they won’t turn up,” he’d say hopefully. “Maybe the bass player will get run over by a bus!”

Instead, after half a term, Ray Brown cheerfully announced that he didn’t need to learn any more – he could already play perfectly well, and was going off on tour in a band with Johnny Devlin. He toured New Zealand and then went to Australia, but had never managed to play a scale or learn where the notes were.

After six months, the wharfie/aspirant piano player had got as far as any beginner would after six months, and faced the bitter realisation that he’d never play like Oscar Peterson. Disappointed, he gave up his lessons, feeling that somehow the teacher was to blame. The guitarist was dismissed as a hopeless case, and the remaining pupils were gradually terminated until, blessedly, there were none left. The Studio would never again be used for its appointed task, and reverted to a bedroom for those musicians with no cat to swing.

Read more in the 3rd and final part: Old George, Gibbo, and the Evils of Drink ... the Importance of Confragination ... Another Drummer Disturbs the Peace ... a Half-G of Wine Gets a Sick Car to the Mount