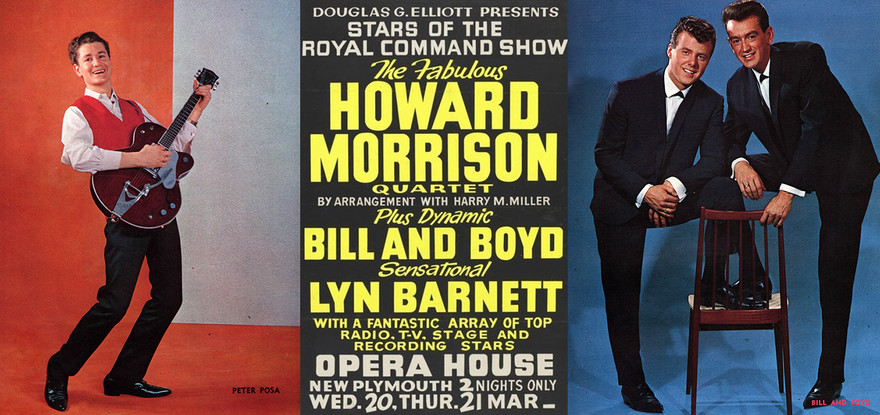

1963: Peter Posa; poster for the Stars of the Royal Command Show tour with Howard Morrison Quartet, Lyn Barnett, Kim Krueger, Bob Paris, Max Merritt and the Meteors; Bill and Boyd. The colour posters are from Playdate.

Television – still finding its feet after its New Zealand debut in 1960 – added to the party during 1963, even though fewer than one in five homes had a set. It was announced at the beginning of the year that two pop shows would screen during the year. In The Groove and Teen 63 would both be produced in Auckland’s AKTV2 studio in Shortland St and screen on alternating weeks, starting in mid-February.

The Kevan Moore-produced In The Groove was a popular programme in 1962. Clyde Scott had been the compere but was unavailable for the 1963 season due to business commitments. This opened the door for Colin Broadley to take over as compère. Broadley had a similar amateur theatre background to Scott, and he presented well on camera. Scott would appear twice as a guest artist during the year.

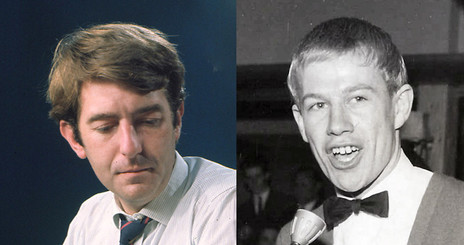

Kevan Moore, producer of TV's In the Groove; Clyde Scott, singer and host of Teen 63.

The first 1963 episode of In the Groove beamed into New Zealand living rooms on 21 February from a studio no bigger than a living room, and it carried on where it left off. The show’s content – although pop orientated to a young teen audience – also aimed at a wider demographic. It featured guest artists across several genres, a panel discussion with audience members on recently released singles, followed by several themed ballet sequences.

The series received favourable reviews after the first show and was described as a tight and well organised show and continued to impress during the year, even after Moore was seconded to Wellington in May to produce After Dark, a late-night variety show for a mature audience. Kevan’s replacement was Peter Webb, another up-and-coming TV producer who started his career in radio. This was his first major producer assignment after cutting his teeth on magazine styled programmes including the popular astronomy series The Infinite Sky.

Ray Woolf and In the Groove host Colin Broadley, 1963. Broadley would soon become well-known as the lead actor in the film Runaway; he was also an early Radio Hauraki host. - Grant Gillanders Collection

Teen 63 would be produced by Ian Watkins (not to be confused with actor and future BLERTA member Ian Watkin) and hosted by Brian Henderson (not to be confused with New Zealand-born compère of the Australian TV show Bandstand). The Teen 63 Henderson, although inexperienced as a host, had appeared several times as an artist on the previous season of In The Groove as a guitarist in the group The Coachmen.

The series started with a hiss and a roar and incorporated a host of elements gleaned from various popular overseas shows. Clyde Scott recalls: “Before Teen 63 started, Ian was asking around for ideas, including from myself. I thought then that perhaps he was struggling – even at this early stage and possibly out of his comfort zone.”

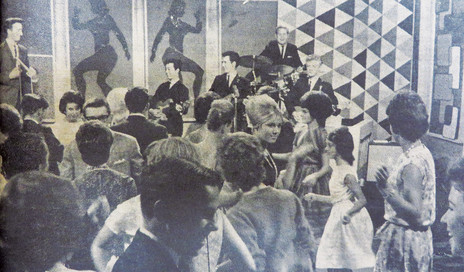

Scott’s early assessment would later prove to be prophetic. The show was recorded in the larger downstairs studio at AKTV2 to accommodate up to 40 invited teenagers to dance while the cameras roamed in between them to create an atmosphere. A Miss Teen Queen 63 contest was to be held in each episode, but this was canned after the first episode along with a panel discussion held with audience members.

The Invaders on Teen 63. - Grant Gillanders Collection

The first Teen 63 episode featured Herma Keil and The Keil Isles, Anne Murphy, Bobby Davis, and Ray Woolf – plus an address from Kenneth Pearson about the Outward Bound school programme. The initial reviews for the show were positive but as the weeks rolled by it soon ran afoul of viewers and reviewers. According to letters to newspaper editors, the main bane of contention stemmed from the unimaginative production, and over-use of camera pans of the invited teenage audience as they twisted along to the performances. “There are only so many shots of twisting teenagers that one can bear,” decreed one critic, while some commentators observed that there were endless shots of gormless teenagers dancing while looking at themselves on the overhead monitors.

Clyde Scott: “I was approached mid-year to take over the compère duties, the rehearsal timetable was conducive to my work obligations, so why not? I don’t know what happened to Brian, but I was brought in to tighten up that role. I realised that things weren’t too good and the show was struggling, so I threw myself into it, maybe trying too hard.”

The sweet smell of success: John Berry gets a hot tip from promoter Graham Dent. - Lou Clauson Collection, Alexander Turnbull Library, Ref: PA1-f-192-31-16

The Auckland Star critic John Berry wrote, “Clyde is a trouper and is conscious of the show’s limitations and tried his best to imbue it with life.” A failure by producer Ian Watkins to address some of the concerns quickly lead to it being axed prematurely in August. One night, just before filming, Watkins was accidently hit by a car crossing the road near the AKTV2 studio on Shortland Street. He was willing to carry on with that night’s show, but common sense prevailed and he spent a few days at home nursing a broken right arm and lacerations to his face. Peter Webb temporarily took over production duties.

Quick as a flash, AKTV2 announced that the show would cease in two weeks. Maybe in a bid to stave off the inevitable, the last two shows saw a lift in vitality – but alas too late. In hindsight, Watkins was possibly not the best choice to produce a teen-orientated show. He was a veteran radio host who started his career in 1940 before working for the television side of the NZBC once it began broadcasting in 1960. At the time of Teen 63 Watkins was in his mid-forties, but with his well-groomed white hair looked like he was in his late 60s. Before and after Teen 63 Watkins’ niche was middle-of-the-road shows Have A Shot, A Song of Twilight and the religiously themed Songs of Praise.

Possibly as a consequence of Teen 63 floundering, the NZBC arranged for a series of compulsory 10-day production workshops to strengthen and standardise production standards.

Clyde Scott: “The main problem was that local television was still in its infancy. The bulk of our producers and technicians all came from a radio background and were still learning on the job. Radio never serviced teenage pop music programmes all that well so we can’t expect them to excel in the television world.”

The Embers at the Shiralee (L-R): John "Yuk" Harrison, drummer Mike Kelly, saxophonist Willy Schneider, singer Joy Yates, pianist Mike Perjanik, and guitarist John Willetts. - Auckland Libraries 1269-E0745-15

Meanwhile, the live scene was exploding. Auckland became the mecca for bands from all over the country. The bulk of Auckland’s clubs were in a small compact radius of the CBD, unlike the other major cities where the bulk of teenage dance halls and clubs were more suburban. Most of the inner-city clubs were only metres from Queen Street, and the distance from the bottom of Auckland’s CBD to the Symonds Street end of Khyber Pass, where the Oriental and St Seps were located, is under 2kms – a brisk 25-minute walk.

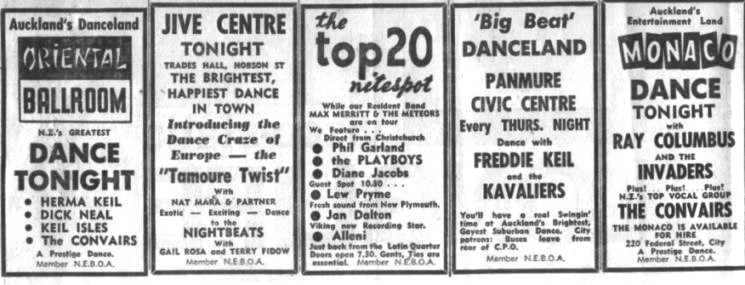

The lively Auckland club scene was spearheaded by an invasion of Christchurch’s top bands and performers. These were Max Merritt and The Meteors, followed by Ray Columbus and The Invaders, and Bobby Davis and The Wanderers. In April they were joined by The Playboys, who featured Diane Jacobs – aka Dinah Lee – and future folk singer Phil Garland.

The Playboys were handed a golden opportunity by Max Merritt, whose group had a residency at the Top 20, one of the city’s top clubs. The Meteors were asked to appear on a month-long tour of the North Island as part of the Stars Of The Royal Variety Show, which also featured The Howard Morrison Quartet, Lyn Barnett, and many others. The show had taken place in Dunedin in February, with Queen Elizabeth II in attendence. However, for the June national tour, Merritt needed a replacement band for the Top 20. He quickly thought of The Playboys, and put a call through to see if they would be interested in coming up to Auckland for the month.

The Playboys (L-R): Graeme Miller, Mark Graham, Brian Ringrose, Dave Martin, Phil Garland, and Diane Jacobs (Dinah Lee)

The Playboys didn’t need to be asked twice, they jumped at the opportunity: this could be their big chance. Jacobs took holiday leave from her job at a paint factory and the band hit the road. The Playboys performed every night of their month at the Top 20, playing 45-minute sets with a 30-minute break. After the variety show tour finished, The Meteors reclaimed their residency, while Jacobs and The Playboys packed up and returned to Christchurch.

Jacobs and Garland had been seduced by the vibrancy and the bright lights of the Auckland scene and immediately made plans to return by mid-year. The pair left The Playboys and Jacobs handed in her notice at the paint factory; by early July they were back in Auckland, initially at St Seps with Allison Durbin’s sister Lorraine.

Dinah Lee: “My first priority after moving to Auckland was to get a job. The first was as a clerk at Farmer’s department store. The second was as a fitness instructor at the Silhouette Health Studio, which was just down the road from the Top 20 club. They had lunchtime gigs there. I would run down during my lunch break in my uniform – which consisted of a pink top, black slacks and heeled shoes – jump up on stage, sing a couple of songs, and quickly sprint back to work. I wasn’t paid, although I got a free cup of Kona coffee – if I was lucky.” It would be early in 1964 before Dinah Lee and her new mod image exploded onto the scene.

Auckland nitespots, 1963: advertisements from the Auckland Star.

New clubs seemed to appear weekly. The Monaco had opened the week before Christmas 1962, followed by the iconic Top 20 a few weeks later. More clubs opened during the year including the Tiki Lounge, Surf City, The Avon, Friday Nitespot (aka The Uptown Club), Pacific Rendezvous, the Whiskey A Go-Go, and the re-opening of the Civic Wintergarden. Some of these clubs lasted a matter of weeks or months, while others stood the test of time or carried on after a name change.

Guest artists from other centres – mostly Wellington – who were due to appear on In The Groove and/or Teen 63, would arrive in Auckland early in the week, for rehearsals before the broadcast. They would then appear at several clubs in the city over the weekend before heading back home.

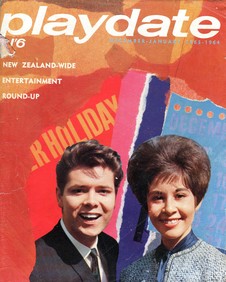

Cliff Richard and Helen Shapiro on the cover of Playdate, December 1963-January 1964

A vibrant scene always breeds a lively press, and 1963 was no exception. Four separate pop magazines featuring strong local content hit the stands that year – a feat that has never been repeated. Countdown, Hit Parade, NZ Teen Scene and the monthly Playdate magazine. The latter magazine, published by Kerridge-Odeon, primarily promoted the latest movies but also published a respectable amount of local pop music news and profiles. This quartet of publications all vied for pop fans’ attention but by mid-1964 only Playdate was still publishing.

The year began with a national tour by the world’s undisputed king of dance crazes, Chubby Checker, whose massive hit ‘The Twist’ was now nearly three years old. In January 1963 he toured the country for two weeks of pandemonium, with scenes that wouldn’t be seen again until The Beatles’ arrival 18 months later. To welcome him, special free buses took an estimated 3000 fans to Auckland’s Whenuapai Airport. Prior to his visit, Checker’s latest craze ‘The Limbo’ had reputedly sold 13,000 copies. His tour culminated with an invitation by Howard Morrison to be his guest of honour in Rotorua for a special hangi.

Chubby Checker was the only major pop star to tour New Zealand during 1963, although the more mature music lovers were well served with tours by Acker Bilk, Louis Armstrong, Vera Lynn, Kenny Ball and His Jazz, and Eartha Kitt. (In Sydney, before arriving in New Zealand, Kitt recorded a Johnny Devlin song ‘You’re My Man’ as her next single.)

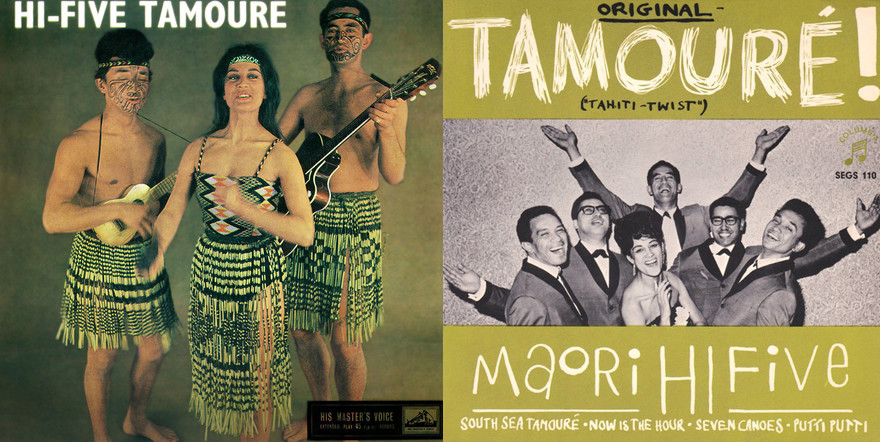

Māori Hi-Five EPs from 1963: Hi-Five Tamoure (HMV NZ), and Tamouré (Columbia, Sweden)

Although the worldwide twist phenomenon was starting to wane, New Zealand was still very much twist crazy right through until the end of the year, at times to the annoyance of many. During 1963 there were ongoing plans to introduce new dance crazes, starting early in the new year when RCA (NZ) announced that they going to promote the “tamoure” craze – based on a Tahitian dance – with a clutch of themed album releases. The Māori Hi-Five recorded an EP titled Tamouré for Columbia Records in Sweden just prior to returning home after three years of traversing the globe. The Hi-Five were eager to introduce the dance to New Zealand, where the EP was released as Hi-Five Tamoure.

Several clubs highlighted the craze during the year, most notably The Sundowners at the Jive Centre. But interest in tamoure quickly evaporated, the general consensus among the locals being that it was just too much hard work. Promoter and dance club owner Phil Warren announced a twist ban at several of his clubs, although he had launched the dance in Auckland. The idea was more likely to be a publicity stunt, and possibly had little success.

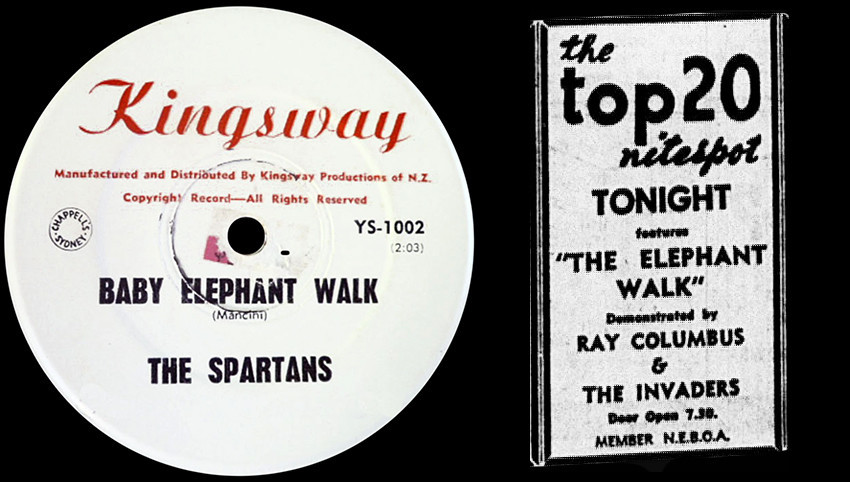

What dance move was next? From November 1963 – a year after its US release – the John Wayne film Hatari was a big hit in New Zealand. The film’s theme song was the Henry Mancini instrumental ‘Baby Elephant Walk’. A local instrumental guitar version was released on Kingsway by The Spartans, an Auckland-based band. Ray Columbus took it a step further by developing “the elephant stomp” to the same tune, which he demonstrated for a month or so at several Auckland clubs.

Main trunk line: Auckland group The Spartans release Henry Mancini's Baby Elephant Walk on Kingsway, while Ray Columbus and the Invaders introduce The Elephant Walk to the Top 20 dancefloor.

According to the few (very few) who recall Columbus’s dance, it consisted of the feet stomping while the hands are brought up to the ears and flapped forwards and backwards, to mimic elephants’ ears. Then both arms joined together and swayed from side to side to represent an elephant’s trunk. Columbus would go on to have better success with his Mod’s Nod dance the following year.

Several attempts were made to introduce the Australian dance craze “the stomp” into New Zealand. Johnny Devlin – on the back of his new single ‘Stomp The Tumbarumba’ – returned home for a weekend to demonstrate the dance to a packed house at Christchurch’s Theatre Royal.

In another bid to popularise the stomp, during early October the Surf Club opened at the former Tivoli theatre on Auckland’s K Rd, to cater for stomp aficionados. Up-and-coming Australian singer Billy Thorpe – before he started his recording career – was bought over to open the club. But this was to little avail: the Surf Club folded before the year was out.

Teen Scene magazine organised a well-attended Surfing Stomp show at the Wellington Town Hall, with stomp dance instructors on hand. Lou and Simon briefly jumped onto the stomp bandwagon; during a mid-year stint in Sydney, their “Māori stomp” appears to have gone down well, but it died a quick death back home.

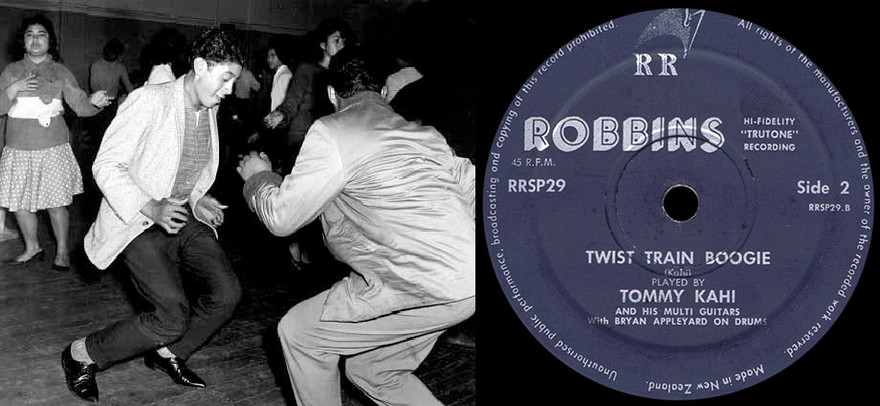

Dancers doing The Twist at the Māori Community Centre, 1962 (Ans Westra, Archives NZ, AAMK W3495/28H, CC 3.0); Tommy Kahi's Twist Train Boogie (Robbins, 1963)

Despite all these different dance crazes being dangled in front of our teens, New Zealanders were obviously content to carry on twisting to their hearts content. Nationwide, twistathons were a big part of the scene throughout the year. A twistathon is a dance marathon in which participants dance for an extended period of time to raise money for charity and a cash prize, not to mention bragging rights. The best local documented record of this phenomenon is Twisting, a 52-page publication written by Lyall Smillie for the South Canterbury Museum in 2022, which chronicles the three twistathons held at Timaru and Temuka during 1962-1963. Most regions held similar events, although the Levin council refused a permit for a their local twistathon by citing public health and safety concerns.

Perhaps the last mention on the subject lies with Dave Hicks (18) and Charlie Witehera (19) who, in late October, twisted their way to a 124 hour and seven-minute world record, beating the previous record by over two hours. In saying that, it doesn’t appear that an official world record ever existed, apart from one Guinness Book of World Records entry in 1962, awarded to an English twister who sustained a measly 32 hours.

Driven by a new wave of baby boomers and emerging musicians, the New Zealand pop music scene in 1963 was vibrant and competitive. While The Beatles are often credited as the catalyst for global change, their influence in New Zealand only gained traction mid-year, by which time the local scene was already thriving. ‘Please Please Me’, The Beatles’ first single released in New Zealand, arrived in April 1963; ‘From Me to You’ followed in May. Remarkably, about one-third of New Zealand records were original compositions – on par with Australia and even comparable to the UK.

Though the world would be transformed by Beatlemania in 1964, New Zealand in 1963 enjoyed its own flourishing musical scene. It was a great place to make music – and dance.

--

Read more: Lights, Camera, Action – rock’n’roll, baby! Part One