A quick glance through Judy Bailey’s career shows that she has had an extraordinarily full one in various areas of music: classical musician; jazz pianist, composer and arranger; concert performer; television and recording session musician; composer of advertising jingles; musical director for club entertainers; teacher at the NSW Conservatorium of Music; jazz educator in the schools: cultural ambassador for Australia on overseas tours; composer of children’s music for ABC Radio; teacher of “music and movement” in schools; member of the Music Board of the Australia Council; lecturer and performer in the Sydney Opera House’s Bennelong Program; and, not least, winner of the inaugural APRA Music Award for Jazz Composer.

Obviously, these amount to a substantial catalogue of achievements and when, in the future, students of the arts and culture in Australia are, hopefully, writing the biographies that are much needed of our major musical artists, the book on Judy Bailey will have to be a large one.

(Perhaps she will write that book herself and achieve a credit as an author. If so, she will undoubtedly throw light on a very under-researched period in the history of Australian jazz – the modern era in Sydney, which has been the major engine-room for Australian jazz as a whole over the last 25 years. During that time, Judy Bailey has been a central figure).

It is not entirely surprising that Judy Bailey is an improvising musician and, in fact, highly values the component of improvisation that is part of her make-up as a composer. In an interview recently with Janice Slater, she was struck by a sudden insight that could well be the key to her personal philosophy: “In a sense, aren’t we all improvisers?” she declared. “One’s whole life is an improvisation really, when you think about it, and I’d never quite thought about it till this very moment!”

This sense of letting things fall into place naturally, of adapting to circumstances, rather than making things happen, is a sentiment that Judy has often stressed: she seems to have floated through life on a cloud of placid acceptance. “One of the things that constantly amazes me,” she said, “is how adaptable human beings are – how adaptable life is ... And, of course, adapting to the circumstances is all part and parcel of improvisation.”

“A musical career is not something I made up my mind about, particularl ... it’s just something that evolved.”

Perhaps the best example of Judy Bailey’s propensity to improvise life itself is her remaining in Australia as a permanent resident. She had come to Sydney from New Zealand in 1960, intending to go on to England or the United States to pursue a musical career. Already an accomplished pianist, she was recommended by another New Zealand pianist, Julian Lee, to the musical director Tommy Tycho, who, at that time, led a television orchestra at Channel 7. She became Tycho’s resident pianist, beginning her musical career in Australia virtually at the top; she has remained there for over 25 years.

In New Zealand, of course, she already had a substantial music education, and some professional experience. She was born in Auckland, but raised in Whangārei, a small country town some 90 miles away. She always loved music and began ballet lessons at the age of seven. At 10, almost by accident, she switched to learning piano. Six years later, she achieved her ATCL Diploma, the performer’s diploma of the Trinity College, London.

Meanwhile, she had felt the influence of jazz. At the age of 12, she heard recordings by the pianist Fats Waller and, during the following years, occasionally heard the music of pianists like George Shearing and Horace Silver. After completing her classical studies at 16, her interest in modern music developed rapidly, and she cites Stan Kenton, Lennie Tristano and Lee Konitz as major influences. She commenced arranging and composing jazz with the 16-piece Auckland Radio Band and with various small groups.

“A musical career is not something I made up my mind about, particularly,” says Judy. “The love of music has always been there. It’s almost second nature to me; I never thought consciously of making a career of it; it’s just something that evolved.”

She was similarly fatalistic about her good fortune in Sydney. “Opportunities came up to gain some immensely valuable experience that probably I would not have had access to, had I gone to London. I was so fortunate; it seemed as one job finished, another started.”

Throughout the 1960s, Judy Bailey devoted much of her professional career to studio playing. In addition to Tycho’s orchestra, she worked with Don Burrows at the ABC, with John Bamford at Channel 9, then with Jack Grimsley at Channel 10. Over eight years of solid television studio work, she had opportunities to write for these various orchestras, spurring her interest in composition.

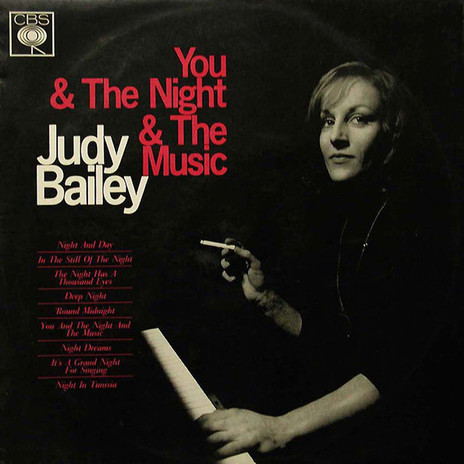

In 1964, Judy recorded her first LP, You And The Night And The Music, accompanied by Lyn Christie (bass) and John Sangster (drums). It included one of her earliest compositions, ‘Night Dreams’.

Judy Bailey - You & The Night & The Music (CBS, 1964)

By 1970, however, she still had only a handful of original compositions to her credit. Other than ‘Night Dreams’, they were ‘Fat Lady Waltz’ (also called ‘Judy’s Waltz’), ‘Silver Ash’, Orpheus & Euridice’, ‘Seascape’ and ‘Two-Part Sketch’. It was only after 1970 that she increased her interest in writing original material and blossomed as a composer. Ironically, her increased output as a composer occurred at a time of extreme difficulty in her personal life.

In 1968 she married, without feeling that she was sacrificing a professional career for the sake of a family. For her, marriage was a natural development at a stage in her life when it seemed right. “I guess I always wanted subconsciously to have children,” she says, “and when it eventuated, it was the most natural thing in the world, and the most delightful thing to happen.”

Still, she and her husband separated after four years, and in 1972 she was left with two small children, Lisette aged three, and Christopher aged one, to raise on her own. Such was her resilience, however, that she was able to convert this period into a positive experience. “It was a difficult time, but you cope. Perhaps by having the extra chores which go with that particular set-up, you learn more of what you need to learn at a faster rate.”

Judy was determined to be at home during the day when her children were small. Although she cut down on her musical involvement during this time, she was able to make a living playing music in the registered clubs at night, while they were asleep in the care of a babysitter. She was, for a time, musical director for the entertainer Barry Crocker. “This meant that Lisette and Christopher didn’t miss out on me at all”, she says, “but I missed out on a lot of sleep for some years.”

Judy feels that the experience of motherhood had a decided effect on her music: “I felt quite different, more confident; I felt that I’d matured in many ways, and that carried over into the music. I was not so afraid of feeling that I had to measure up to other people’s expectations.

“That’s something every young musician finds difficult to cope with. When you’re learning a craft, you have all sorts of examples upon which to model whatever you’re doing, and that’s part of the learning process, until you finally mature as an artist, and have the courage of your convictions. You come to the point where you produce something where you feel you can say, ‘well this is a statement I feel comfortable with, and if people enjoy it, that’s great; if they don’t enjoy it, well it can’t be helped’.”

During the 1970s Judy was involved in a number of ABC radio and television programs for children, where she was called on to compose. She also composed for the productions of the Marionette Theatre of Australia Whacko The Diddle-o! and The Mysterious Potamus; and the occasional piece for films and television.

In 1974 she had formed a brilliant jazz group, the Judy Bailey Quartet, with herself on piano, plus Ken James (saxophones & flute), Ron Philpott (bass) and John Pochee (drums). This group recorded the LP One Moment in 1974, featuring the title track which, in another orchestral form, would go on to win the APRA Award in 1985; and with the vocalist Denise Keene, the LP Colours in 1976. In 1978 her LP Judy Bailey Solo was released, which included eight of her compositions for solo piano: ‘Rag Number Two’, ‘Snowflake’, ‘Jude’s Cakewalk’, ‘Fat Lady Waltz’, ‘Jude’s Boogie, ‘Rag Number One’, ‘The Spritely Ones’, and ‘Ningana’.

Judy Bailey Quartet - Colours (Eureka, 1976)

By 1978, Judy Bailey had achieved sufficient status as a composer to be included in the Australia Music Centre’s series Meet The Composer, a series in which leading composers from various musical areas spoke about their work and music, and were questioned by a live audience. Judy spoke with some eloquence about the unique nature of jazz composition:

“The business of composition is generally regarded as a process that starts with the composer, first of all, getting an idea for the music,” she said. “Various composers refer to it in different ways.

“They might say, ‘I had an idea, or there was a little motif which occurred to me, which I felt I’d like to develop, in some way’ – whether it be for a chamber group, a string quartet, or symphony orchestra, or whatever. Then they sit down, and with a great deal of labour and love they develop that original idea or motif, and it comes out the other end as a full-scale work, which you go along to hear in a concert hall, or you hear on a recording.

“There you have the business of somebody sitting down at a desk, and actually physically writing out the notes on the score paper. With the sort of music that I’ve been associated with for so long, it’s a little different. And, because of the difference, it took me a long while to even consider the notion that I might, perhaps, be referred to as a composer.

“The reason for this is that jazz music involves not only written notation, but also the use of improvisation. In fact, when the jazz musician has finished playing what is the written part of the music – what we call the ‘head’ – he then continues to play, except that it’s then improvisation. And improvisation is really nothing more nor less than what I would call ‘instant composition’.

“Some of this improvisation is brilliant, some of it is mundane and boring, and between those two fine ends of the spectrum, you have a whole range of ideas and exciting. interesting music-making. And if every jazz musician who has ever played a brilliant solo in his life was called upon to transcribe what he played, then we would have added to the wealth of composition as we know it. But usually what happens is that jazz musicians go about their improvising, and usually it just goes up into thin air: it’s lost forever, unless, of course, it’s recorded on the spot. And then it’s preserved forever. The improvisation isn’t often transcribed. Usually, I suspect, because it’s much too difficult.

“So the amount of actual notated jazz composition, as such, has been fairly small, but it’s growing. The actual library of jazz composition is growing steadily. And in this country, it’s been really encouraging, because in the last few years. Australian musicians have started to develop a belief in their own talent. They’ve started to sit down and write what they feel, what they think, what they observe, and they’re starting to produce some very important works. Usually jazz musicians don’t come up with works of great length or breadth, but the content is important. One of the reasons that they usually don’t indulge in works of great length, as far as written notation goes, is because to do that would eliminate a lot of the area that is reserved for improvisation. And if you cut out your improvisation, then you lose a lot of the basic characteristic of jazz (not to mention the fun). Sure, there’s the serious area, and we all know that, but music should be fun too. And, believe me, there’s the greatest fun to be had in making it up as you go along. And I don’t want that to sound as though every jazz musician plays for the sheer self-indulgence of it. There are serious jazz workers, who I consider, are able to produce a form and a structure that is every bit as valid as the classical works that we know about.”

Like a great many jazz composers – indeed composers of any sort of serious music – Judy has had to struggle to get her work recorded. Having music on LP, so that it can be broadcast, is the first step to recognition as a composer. Yet, her experience as a recording artist during the 1970s was a disillusioning one. “I’ve not pushed in that direction lately”, she says. “I haven’t recorded for six or seven years, because I got my fingers burnt, I got soured with recording albums because I haven’t received a cent in royalties for my last album, and had only one royalty payment for the previous album.

“But I am anxious to record again as soon as I can because I have a heap of original material which I would like to get down. For better or worse it’s a product something tangible for all the hours, the years, the emotional sweat that goes into producing something of your own. If I don’t get it down on record, it’s just going to keep floating around in my head, and maybe that would be a shame.”

Her concern for Australian composition is applied, not only to herself, but also to other jazz composers. For a long time, she has been an advocate for local musicians writing and performing their own works. She encourages the saxophonist Col Loughnan and the bassist Ron Philpott who, with the drummer Ron Lemke, make up her present working quartet, to produce original works they are both excellent composers – and she makes a point of featuring them in the quartet’s performances. (The Judy Bailey Quartet toured India, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Burma in February/March 1986. The tour formed part of the Australian Government’s Cultural Relations Programme … Previously her quartet, with Pochee on drums, toured Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Brunei, and Singapore in 1978. In 1984 Judy Bailey and Ron Philpott performed as a duo at the Singapore Festival.)

“I think that it’s essential that all Australian musicians start to feature their own compositions, and I have always encouraged my students at the Conservatorium to bring along their own work. If they’ve never done any composing I try to encourage them to set about doing it. Often, there have been some wonderful, surprising results, and I believe we’ve got a wealth of composing talent untapped yet in this country.

“I’ve been gratified at the number of people who have been regularly coming up and asking me to play my own compositions, and that’s a really nice feeling.”

Where does Judy Bailey go from here? She just completed, in early 1986, four years of service on the Music Board of the Australia Council, and can look forward to, at least, a little more free time which she may devote to composition. She has been interested for some time in the literature of Henry Lawson and C J Dennis, and has thought of writing suites based on their writings, just as John Sangster did with the works of Tolkien; she would very much like to compose music for films, as the occasional commission in that area has whetted her appetite; she hopes to find time to finish some straight classical works, particularly a piece for French horn and strings she has been working on; also, she wants to transcribe some of her own recorded music for the benefit of students and others.

“A lot of people have asked me if they can get the music to my compositions, and I usually give them lead lines and chords that I’ve dashed out myself. But I know a lot of people would like to be able to buy a published copy. It would be a real chore for me to sit down and write all this stuff, just as you would a normal piano score for a classical piece, but I somehow feel a sense of duty to sit down and do that.”

Still, whatever the future holds for Judy Bailey, she will not be pushing in any particular direction, unless it feels right. “I don’t want to make any rules for myself. I want to allow things to happen that need to happen, and so I’m not working to a plan or a formula. I guess a lot of people would call that being disorganised and totally lacking in ambition. Well, so be it.”

--

This article first appeared in APRA (Australia), March 1986, and is republished with permission of APRA. Eric Myers was editor of the Australian Jazz Magazine, and wrote jazz reviews for The Australian and Sydney Morning Herald newspapers. His features and criticism are collected, along with other Australian jazz writers, at this remarkable website.